We RAT on Arts Fission’s Angela Liong

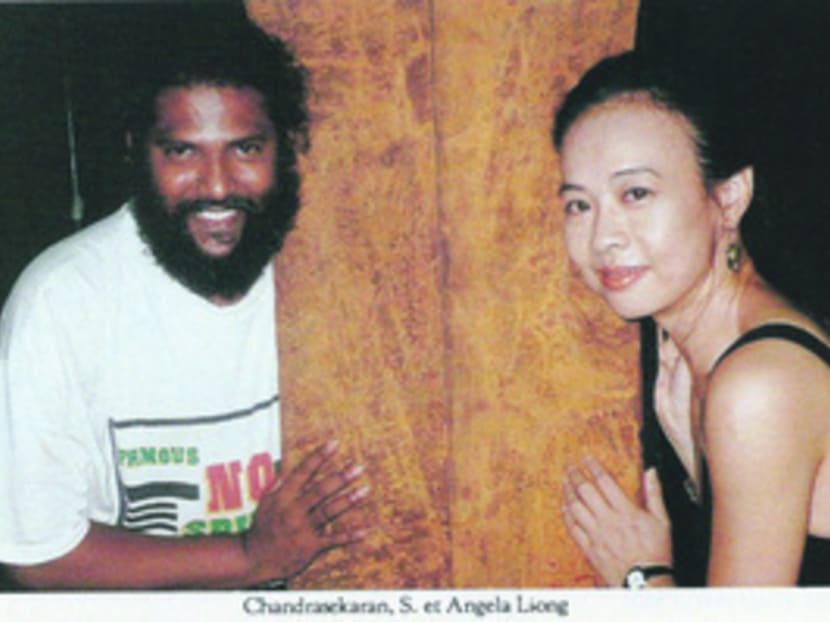

SINGAPORE — When you think of Arts Fission, chances are, you’ll also think of Angela Liong. But how many of you remember the fact that back in 1994, the contemporary dance group was co-founded by visual/performance artist S Chandrasekaran?

SINGAPORE — When you think of Arts Fission, chances are, you’ll also think of Angela Liong. But how many of you remember the fact that back in 1994, the contemporary dance group was co-founded by visual/performance artist S Chandrasekaran?

Let that sink in for a while. A future Cultural Medallion recipient from the world of dance and an artist who was part of the 1988 landmark group show Trimurti coming together to set up what would become one of the most respected performing arts groups in Singapore.

Arts Fission is celebrating its 20th anniversary this year with the 10-day event called Make It New, comprising performances, exhibitions and talks at the National Design Centre, Arts House and the Library@Esplanade.

To get you in the mood, here’s the transcript of my interview with Liong, interspersed with nuggets from other interviews with Chandrasekaran, as well as former Arts Fission members Elysa Wendi and Scarlet Yu.

(Arts Fission’s Make It New runs from Jan 30 to Feb 8. For more information on the events, visit http://www.artsfission.org/.)

***

Q: Arts Fission is marking its 20th anniversary this year. Can you share how it all started?

ANGELA LIONG: At that time, (S Chandrasekaran) and I were both teaching at NAFA, tucked away at the old Mount Sophia campus. He was in the Fine Arts department and I was in the Dance department. In 1992 we started a small multi-discipline workshop for our students. We felt it would be interesting to get the arts and dance students together, so we did a site-specific project, and we didn’t even have money to run the workshop. The school gave us $600 and that was it. It was really very interesting times. I got to know all these students from different arts disciplines. And even for my dance students it was an eye opener. How do we make movements in a tiny corridor, in a classroom, at the staircases… But it was difficult to carry on and continue more of this kind of multi-discipline projects, so I said why don’t we just go ahead and form a company? If we had a group, we thought it was easier to get funding. So we went to a lawyer to register in 1994, end of May. There were a lot of legalities involved but there was no turning back.

S CHANDRASEKARAN: We started off as an experimental group. It’s around the time that installation art, mixed media was picking up in Singapore. She asked me for workshops for classes, and we thought it was a good time to explore our differences.

Q: What was the dance scene like back then? Were there other groups around?

ANGELA: (Goh) Soo Khim formed (Singapore Dance Theatre) in 1988 (with Anthony Then) and that was the only professional group around. The other full-time dance group was PA (People’s Association Dance Company). In the early days, dancers like (THE Dance Company artistic director Kuik) Swee Boon, Sylvia (Yong, Kuik’s wife), Jeffrey Tan have all worked with the PA Dance Company

So when we started our group, we thought we should form some kind of collective to enable us to practice the kind of arts we like. I had no intention to just do the conventional kind of dance. I was very into cross-disciplinary arts because that kind of energy always intrigued and excited me.

Q: So you both weren’t thinking of Arts Fission as a dance company?

ANGELA: That’s why it was called Arts Fission — not fusion, not frisson. That it comes from a general core but when it splits, all the individual atoms retain their identity. We liked that idea. Each individual can explore but at certain times, we could also interface and work together, but it doesn’t mean that we have to work together on everything all the times.

CHANDRA: We explored stage design, installation, materials, ideas. That’s where I came from because I was quite into this multi-disciplinary approach. I don’t think my contemporaries, Lee Wen, Vincent Leow, were into theatre. Even Zai Kuning wasn’t into theatre at that point, I think. They were more into performance and installation.

Q: So where did the name come from?

ANGELA: We did a dada exercise. (smiles) We took a dictionary and flipped the pages. That’s where the word “fission” came. We preceded with the creative energy of the dotcom companies — where a team of creative people who had different specific expertise agreed to come together, have a common goal, and just play ball.

Q: So was it just the two of you at Arts Fission?

ANGELA: There were four founding dancers, too, like Wong Wai Yee, from my first graduate cohort at Nafa (who later married Ricky Sim, who was also my student at NAFA, and together they started the Moving Arts Company and Raw Moves), and Alvin Quek who’s now in the UK practicing as a Pilates trainer. During my time (at NAFA), there were fine art students like Lim Chin Huat, Goh Boon Teck, they were all studying at the Fine Arts Department. Chin Huat finished his Fine Arts Diploma and decided to study dance. And, of course, (Tan) How Choon was also in the dance department. The two later started their own company (ECNAD). (For Arts Fission), there were four regular members with some supplement from the dance students, but it still wasn’t a full time practice. If we had a project, we’ll come together. Because Chandra had his fulltime teaching job, I was also holding down fulltime job all the way till I quit from LASALLE in 1999.

Q: So tell us about your first official show as a group.

ANGELA: How the inaugural performance, Mahabharata — A Grain of Rice, came about was that one day Chandra and I were having pizza at Plaza Singapura and we were commenting about how people nowadays eat all these fast food. Rice as an Asian staple came up and Chandra said that in the Mahabharata, there was a chapter about a grain of rice. So he went home and took out this ancient, antique copy of the Mahabharata that his grandfather left him. We photocopied that book and there was that chapter. We thought it was a fantastic title.

Q: That show, which was presented in 1995 at the Festival of Asian Performing Arts, was pretty big wasn’t it? You didn’t start small huh?

ANGELA: We didn’t’ know any better. (laughs). We were naive. We went to NAC and talked to Liew Chin Choy who was festival programme director at that time. He said they could consider commissioning it. It was held at the old Drama Centre and was a multi-media show. We had a team made up of NAFA people. We worked with Philip Lim for the film segments, Chandra did the whole set, a couple graphic design graduates from Nafa did the collateral design. We were cooking rice inside the theatre. At the end of the performance we shared rice with the audience.

And even before the show, there was a little episode. One night, Liew Chin Choy called me up and said, “Angela, the whole Indian community is up in arms against you! Some people are not happy that you are touching on the apsaras of the Hindu religion and have girls in these breast plates performing dance as the fertility goddess...” Because we made these voluptuous breastplates that was a direct take from the carvings of ancient Hindu temples. But come on, we were looking at these as fertility symbols! Chandra designed the breastplates from kitchen strainers (laughs). I’m not quite sure who wasn’t happy but the show went on fine. We didn’t change anything. We didn’t think we were being disrespectful.

CHANDRA: A Grain Of Rice was very much connected to what I’m working now towards. It was how the power of one grain of rice can change everything and how it transformed the body on many levels, both mythological and everyday realities. We brought all these rice cookers on the stage and it was amazing… I started to realise how much we brought materiality into the dance scene — I would design costumes, the stage…

Q: What was the feedback from the audiences?

ANGELA: It was great. At the end of the show, we fed everybody. (laughs) We actually simulated (the act) at Hindu temples when the priest comes out and offered rice to the devotees. At the end of the performance, we had a drummer who escorted the audience to the lobby, and there was a little rice shrine installation by Chandra and someone was passing out rice. People were eating with bare hands. Symbolically we were sharing food and referring to Krishna’s episode at the Mahabharata. We were exploring spiritual and physical hunger. The performance was reported by a newspaper from India who wrote an article about this theme.

Q: How would you describe Arts Fission’s performance vocabulary back then?

ANGELA: (For A Grain Of Rice) we didn’t actually use Indian movement per se but took the cue from an understanding of the classical dance form. We used a purely contemporary vocabulary for the performance. The installation was slightly different: We had a rice cooker installation, which framed the space differently. In hindsight, I also think my movement vocabulary has changed drastically since then. In a way I’m glad I’ve actually grown and changed from that. But it was always the idea of borrowing with respect and appropriateness.

What we were setting out to do was exploring what this new kind of Asian aesthetics was. One thing that made the collaboration work is that Chandra and I really enjoyed just arguing and discussing about issues, sometimes until 2, 3 in the morning. And I really missed that kind of camaraderie. Ever since (Chandra) left, I couldn’t find that kind (of creative partner). But while we were together working in the company, it was really intense. I was able to discuss issues with someone I could trust.

CHANDRA: I was a performance artist already then and going into four-dimensional space. For me, the body was sometimes static or passive while the dancers’ body was very active. So I tried to explore this notion of passive/active in the works.

I didn’t take part (in the dances) because I clearly knew my position — they were dancers and I was a performance artist and not interested in choreographed movements. I was more involved in introducing materials and how they can move their body to the materials.

Dance was more Angela’s role. When we collaborated, we had to draw boundaries very clearly. Nowadays they tend to blur, which is good also, but when we started back then, the disciplines was very much divided.

Usually, choreographers don’t work with artists like me. Angela and I had to negotiate. My part was to push boundaries, in terms of stage design, for example, or to push dancers to deal with this kind of medium. The language, medium and the body are the three things you negotiated with.

Q: Could you say that performance-installation was indicative of the creative energies at that time, during the `90s? Or did you think you were doing something different?

ANGELA: Specific to Singapore, very few people were doing cross-disciplinary (work) especially in dance. Most dance companies or groups were either doing very traditional repertories or conventional stage presentations.

It’s slightly different for the theatre groups, with the likes of TheatreWorks who was doing cross-disciplinary, cross-cultural works from the start. And even in visual arts, in those days it was a very vibrant community.

In certain ways, we were probably mavericks. That said, in the past (60s or 70s?), the Bhaskars did take the classic Chinese story of The Butterfly Lovers and reworked it with the Bharatanatyam vocabulary. So I don’t think we were the first, but perhaps we had the benefit of having different resources in a different time, so we were able to carry on consistently and continue to explore what we started out with A Grain Of Rice back in 1995.

(Back then) it was very open, very informal, even if there’s already a cultural institution like the NAC to offer assistance. Nobody was saying you should do this or that. There was no masterplan by the government yet. The ethos was so open among the artists. “You make sounds or noise? Let’s go make something!” No one was really thinking, “How much are you going to pay me?”

It was naive but the main focus was clear for everybody, which was we wanted to learn, explore, to know. The artistic curiosity was very strong and we were driven by that.

CHANDRA: Theatre was a stronger movement than visual art. They were more organised and had direction and vision, like TheatreWorks, The Necessary Stage. But we were also exploring on many levels.

Q: Once you got the ball rolling with A Grain Of Rice, what else did you do?

ANGELA: After, that we did Flower Eaters in four site-specific series. The first series, at The Substation in 1996. It was inspired by Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal (Flowers Of Evil) and we did something quite daring and bold. We were then the first to incorporate the exit door (by the performing area) and make it part of the attachment performance space. We had one group of audience facing one way, and another facing the other, and performers were moving in a conveyer belt like path around them. Nobody would dare do this kind of insane thing back then, okay? (laughs) And we hung mirrors, Chandra did an installation with oil and sand in the corner, so the audience was really busy looking at something. It was really a multi-arts, multi-sensory experience at that time.

We were doing all that kinds of stuff. I think at one time, Chandra was very much into something like what happens during Thaipusam, using needles to pierce the skin. He told me, “Oh, it’s kind of like buying chicken from the supermarket and you lift the skin like this…” (mimics the piercing). I told him I might be convinced but I couldn’t convince the dancers! (laughs). We did have all these wild ideas. I remember vaguely something about fire but how to get the authorities to approve? It’s not like you go to a kampong and set a bonfire… (laughs)

The wild ideas were met with a lot of rigid rules and regulations. Up until today, I’ve been doing a lot of site-specific works, but the biggest hurdle still proves to be the general understanding of what a site performance is and the necessary logistics involved. In fact, it was slightly easier to pull off things in the early days — we could get away with murder cos nobody knew better. (laughs) But now, a lot more things are at stake.

CHANDRA: I was only with Arts Fission maybe for two, three years, then I left to do my Masters degree in India in 1998. I came back to Singapore in 2008 but I had been passive for so long so I stepped down from the company It has taken a different dimension now, I think.

But I’m still doing my own kind of theatre now, Biological Arts Theatre. I’m moving more into life sciences, more into raw information, still working with data but not with dancers. I’ve also been working with different independent theatre companies as well, Recently, I worked with Santha Bhaskar. I’m still very excited with theatre.

Q: After S Chandrasekaran left just a few years after Arts Fission was founded, what made you continue and what direction did you decide to embark on without your co-founder?

ANGELA: Even in my early career, I didn’t have the benefit of a support team behind me. When I was invited to set up the dance department at NAFA, there wasn’t even a secretary or administrator for me. But with Chandra, we’re both hands-on people and were multi-tasking right from the start.

When he left, I was still running departments from NAFA and later to LASALLE College of the Arts (where she moved to set up a new dance programme and served as dean of Performing Arts), I didn’t have the benefit of time and resources.

By then, I was only doing one production a year (laughs). But it was very important to have Arts Fission running. The reason I taught was to nurture and cultivate professional performers to present artistic work on different levels, and also to have good dancers to work with me. But I knew I wasn’t going to stay in the academic field forever. Arts Fission did take a back seat for a while.

Q: But obviously, there wasn’t a yin-yang creative relationship anymore between a dance artist and a visual/performance artist. How did Arts Fission transform?

ANGELA: Well, it kind of moved into a much more movement-based (company). That said, Chandra was also a performance artist. But I would concede that my dance vocabulary was more in keeping with the concerns of technical dance movement at the time. I think, in hindsight, had Chandra been around, perhaps I would have been pushed into looking at something even more far out, like “You just stand there and bend your back ten times.” (laughs) Perhaps his presence as a performance artist would generate a certain kind of energy to look into some unlikely movement style or vocabulary.

But the key concept from our early days, the search for contemporary Asian aesthetics and always making reference to our traditions, was still very important to me. Because of that, the company was still going on and I still continued looking for dancers who were very open to this. The turning point, the watershed, was in 2000.

Q: In what way was 2000 the turning point?

ANGELA: It was when Aaron Khek, who was also my former student from NAFA, returned after his study in Hong Kong with his partner Ix Wong, who had danced with City Contemporary Dance Company in Hong Kong. (Both also eventually formed the defunct art collective Ah Hock And Peng Yu). Also, there was Scarlet Yu, who was a fresh graduate from APA, and Elysa Wendi, my student from LASALLE. There was one other APA dance graduate from Taiwan who also joined the company.

And again, we had a commission from the Singapore Arts Festival. (Goh) Ching Lee invited us to do a site-specific work at the newly renovated Hill Street building (the old MITA/MICA), which became NAC’s headquarter. The performance was called Imagine Forest, where we collaborated with T’ang Quartet and visual artist Wang Ruobing, who designed a quadrangle installation at the atrium for the performance.

Q; So basically, the company got its second wind.

ANGELA: Yes, pretty much. Like suddenly we kind of morphed into a brand new company. These new dancers were not students but young artists looking for work to engage in the arts full-time. By mid-1999, they were all returning to Singapore so I thought I should quit my job now (at LASALLE) and focused full-time on developing the company. And in 2000, we also moved here (to Cairnhill Arts Centre). The given artist housing enabled us to really work regularly and rapidly. On average every three months, we were able to present a new production.

Q: And how were the audiences at that point?

ANGELA: I remember we had quite a core audience. At that time, we were able to reach to a bunch of audience who were looking for contemporary and unconventional performances. If you wanted to see something experimental then, there wasn’t that much that could satisfy the appetite of this audience so we were able to reach out to this small core. We’re talking about an audience capacity that is slightly under 200 people (for each performance) and it’s important to keep the number small for more intimate, experimental works. Small theatre venues like the old Drama Centre worked best for this purpose. We seldom had the chance to use bigger venues like Victoria Theatre.

Q: And all the works that were coming out from Arts Fission weren’t just your works right?

ANGELA: From 2000 on, the company members were very, very creative artists. They weren’t only interested in dancing but also into related areas like visual art, music, film, to create their own works. It was really a very wonderful time. Most of the time I would have a creative idea then I would have a lot of sounding boards from them. Someone would conceptualise the movement, someone would design an installation. Ideas were flying around. Normally we would have three, four productions a year and half of them would be by my company dancers.

But there was another watershed in 2007. By then, longtime company members began to exit the company. People like Elysa, Scarlet and Bobbi (Chen) were all starting to embark on a different path in their careers. From then on, I had to literally do all the works as the sole choreographer.

ELYSA WENDI: My involvement with Arts Fission actually started 18 years ago — Angela Liong was the Dean of Performing Arts at LASALLE College of the Arts during my Diploma days. I vaguely remember I was about to quit school since I didn’t think I had any talent in dance. I went to her office one day and asked her to choreograph a solo for me.

In 1998, I did my first solo in the Arts Fission performance called Lost Light — Syonan Jinja Shrine. It was a memorable experience and I joined Arts Fission as full-time dancer and production manager in 1999. I became assistant artistic director from 2003 to 2009.

SCARLET YU: I joined the company in 2000 as a fresh graduate from The Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts. My classmate, Aaron Khek, introduced me to perform in the site-specific project Urban Sanctuary : The Floating Stage Series on the 35th story rooftop of the Centennial Tower. At that time, this performance was bold and was the very first high-rise site-specific performance in Singapore. That was how I landed in this tropical land with no expectation! I was a member as a rehearsal director and performer until 2010.

Q: Elysa and Scarlet, can you share a bit about your years at Arts Fission? How important were your respective experiences in your development as dancers and choreographers?

ELYSA: That was the early formative period of my career as a dancer and choreographer. I cannot recall how many shows I have created exactly but vaguely if I count, I’ve created four full-length works and 20 short pieces in a span of 10 years. The company provided me with many opportunies to collaborate and interact with other artists from different disciplines and conceptually connect with other art forms, cultural practices and our world at large. It also inspired me very much (to consider) the value of literature in layering the substance of dance construction. One notable quality of Angela is her ability to insert her poetic imageries in the pure structuring of dance-making. For this quality and ability, I truly admire her.

SCARLET: I’ve done over 100 performances during my time with the company on a local and an international scale. And I’ve witnessed and participated at the foreground of the arts policy shift, the blooming of community arts practice and the development of contemporary dance in Singapore. I’ve learnt and embodied (the ideas of) “multi-tasking” and “all-roundedness”, which have nurtured a self-sufficiency in me as an independent arts practitioner.

Q: Angela, after this second watershed, what was the next step for Arts Fission?

ANGELA: We never repeated anything from the past. My way of restaging works was to explore the potentials by tackling the same theme and turning it to a different direction. Like for Flower Eaters series, I recently invited one of the early collaborators back and reworked the theme calling it Eat A Bitter Bloom (in 2012).

I don’t operate the company in a conventional way, where inviting guest choreographers to work with company dancers and build repertories is the norm. I like to invite and collaborate with other artists who share a similar aesthetics and the urge to explore the unusual.

And if there’s such a thing as a company masterplan, I think of three things: First, our creative endeavour and experimentation, which is the key reason for our artistic existence. Second, we develop community wellness programs to enrich the quality of life for everyday people. I want to communicate to the general public that the artistic practice we do in Arts Fission can be applied appropriately to engage different communities.

In the past, we’ve worked with at-risk youth using the physicality of dance. We started working with the elderly six years ago. I collaborated with neurologists from the Singapore General Hospital and we’re looking at how we can use creative movement to help people with dementia or Alzheimer’s. We also developed creative movement programs for seniors living in nursing homes or rehab centres.

The last one is education and appreciation of the arts, which includes our weekly enrichment program where we work with children. We were artists-in-residence at the Asian Civilisations Museum for two years, where we used the museum’s artefacts to engage young children in art-making and also reintroduced their young parents to the museum experience.

Some have commented Arts Fission is turning into a community arts company. In the beginning, it bothered me a lot, but eventually, I said I’m going to ignore that because we’re really doing meaningful works that validate our arts practice. And as for the dancers, I want them to understand the communication process with a person in ill health or person suffering from age-related ailments. Because movement is our game, right? I want them to connect our practice to other aspects of life and be thinking dancers.

If you ask me today what Arts Fission is about, I don’t think I can give a definitive answer. Because the company dynamics is very fluid and not frozen into a fossil. And it is still developing and morphing. I like that. Personally that’s what keeps me going.

Q: A couple of years ago, the company was in the news for its problems regarding the tightening of rules for hiring foreigners. How much of an impact did that have?

ANGELA: It was a big thing. I almost dissolved the whole company. Between 2011 to 2013, 80 per cent of of our dancers were foreigners, so when the rule came in, it wasn’t to our advantage. That was the only time I contemplated closing down Arts Fission or for the company to take a long hiatus. Thankfully we didn’t have to do that. Hiring foreign artists had nothing to do with the arts but more about manpower policy and a certain political stance.

But in hindsight, this also forced me to come up with a different way of dealing with the dire straits situation. I came up with an apprenticeship scheme called the Dance Immersion Programme that emphasises empirical training through industry practice. We audition fresh local graduates and they have to complete successfully a year and a half training with us before the chance of full-time employment is offered. In the meantime, we continue to hire seasoned dancers from outside of Singapore to raise the benchmark of performance standard.

This year, we suddenly have a bumper crop of 8 dancers — previously it’s anywhere from four to six and now we have eight, including two apprentices, and half are locals.

Q: As someone who’s been involved a lot in the arts scene, what are some of the challenges and issues you’ve encountered?

ANGELA: I’ve been here since 1984 and I’m privileged to still be working here. The cultural policies have evolved tremendously over the years. In the early ‘90s, most arts groups ended up having to make up for all the shortfalls of sustaining a full-time organisation, no matter how small. It seems needed support or assistance for us have always come around too slow. Lucky for us now, a lot more resources and fundings are available to develop the arts industry. But with this improvement of resources also comes with a different set of challenges. The arts are becoming more commodified. For once I would like to see the real meaning of making arts addressed. I like to see more opportunities for communication between the crossing of disciplines, conversations and activities among the artists themselves. Everybody in the arts community these days seems to be so bogged down by the day-to-day existence and funding committment. There’s no breathing space left in-between. That’s speaking from personal experience.

Q: Would you say that the energy of the scene during `90s is lacking?

ANGELA: We can’t turn the clock back but I would say is I really miss the spontaneity of creating arts in the old days. At that time, we pooh-poohed the idea of formalities, we got in touch with people, we had a little bit of room and space, attended each other’s performances, had the opportunity to explore working together. Now, we’re even more isolated and everyone’s got KPIs to worry about.

It’s also becoming a “project economy”. There’s no such thing as “Just go and do research and if you hit on something then great”. (Now, it’s) “I gave you all that money and after two years nothing? Just research and that’s it?” But newsflash: We will always hit on something. We might not be able to produce a product right away but five years down the road (we might). It’s the concept of time that is tripping everybody.

There are a lot more resources compared to 20 years ago. There are so many different types of funds and grants available now. But ironically, there are also so many hurdles and strings attached to everything. We’ve been pulled left, right and centre in the name of grant requirement. It does distract and take away from the original enthusiastic spirit of exploration.

Q: What about your views on the dance scene in particular?

ANGELA: In the past few years, we’ve seen a lot of companies going into full-time practice. But at the same time, there is a danger. You have all of these people who are in the early stages of their careers. We don’t have many experienced mid-career practitioners. So you have a general environment where people are doing a lot of things but we lack the diversity in terms of dance creation. I think the kind of dance works presented are almost homogenous, which is limiting.

You don’t have dancers who have been practicing for the past six, eight, 10 years. You have new, fresh graduates, from teenagers to those in their early- and mid-20s, but few mature works they could look to, absorb and reflecxt on for their own works. I’m not saying mature work is (automatically) good. What I’m saying is, hey, if a dance-maker has been practicing for years, this person’s work would probably be very different from what a 20-year-old has to offer. We don’t have a continuity in the dance community and, in fact, I feel that in dance, there’s no sense of history. If you’re going to break something, do something new or “avant garde”, you have to be aware of what you’re breaking. It is important to have that historic link.

A lot of the young practitioners are only doing peer-learning, they’re learning from watching each other’s works. Nothing wrong with that but again, you do need the balance of more mature works to reference and benchmark in order to grow.

Q: But at the same time, isn’t the growing number of practitioners and new groups good for a burgeoning scene?

ANGELA: That’s true. But on the other hand, and I’m gonna be very straightforward, some of these mid-career dance makers need to continue more on their own creative journey instead of busying themselves by expanding their dance enterprises. They should work their butts off and make sure they’ve done enough for themselves before moving on to lead other younger dance entrants. Where is their body of work? Performing or choreographing for five, six years, is hardly a substantial track record. What have they found out from their creation?

I would, in a critical way, say that these people need to delve in and do some more “homework”. The attention is too much on “young, up-and-coming”. That can be an exciting beginning, but we’ve also got to pave the way for enough diversity and allow space for continuous practice for these “young and up-and-coming” dancers to learn from their mistakes and understand their own practice. If people say the their first work is wonderful, what about the second or third ones? How will they sustain their work and ensure artistic growth? Sustainability is difficult. They might burn out and eventually, they’ll be doing and speaking nonsense.

What I’m saying is, there’s got to be baptism by fire along the way.

Q: To end on a positive note, what about anything right that’s happening in the scene?

ANGELA: Am I being negative? (laughs) After all these years, we’re finally getting dancers who show up with better physiques and more proficient techniques. They are receiving better training and that’s very exciting to see. Now you have SOTA, too, besides just the two tertiary institutions, NAFA and LASALLE.

What I’m saying is we have to work a lot more on the thinking, conceptual part of the dance. Right now, it’s just dancing. You have to hit a balance. We do see, here and there, some ideas which are very strong but in terms of execution, it’s clumsy or they don’t have the right tools to execute it — or vice versa. You can be a dancing machine, flipping and doing all these stunts, but where are we going with this? At the end of the day, does it touch the audience beyond just “Oh, wow!”

But aside from better training, another positive thing is that we are beginning to see a few young people coming back after their studies abroad and having the courage to say, “I want to practice arts full time and nothing else for now”. I’ve met a lot of visual artists and new media artists who are committed to doing just that. But I haven’t seen enough of this kind of commitment happening in dance, yet. Hopefully with more arts funds available, and a more robust arts industry developing, the career choice for more young dancers to make dance as a full time vocation can be realised soon.