On climate technology, China should think small

It is a common sight in rural China: Rows and rows of low-rise apartment buildings, often topped by solar water heaters the size of kitchen tables. By one estimate, 30 million Chinese households rely upon the devices for hot water.

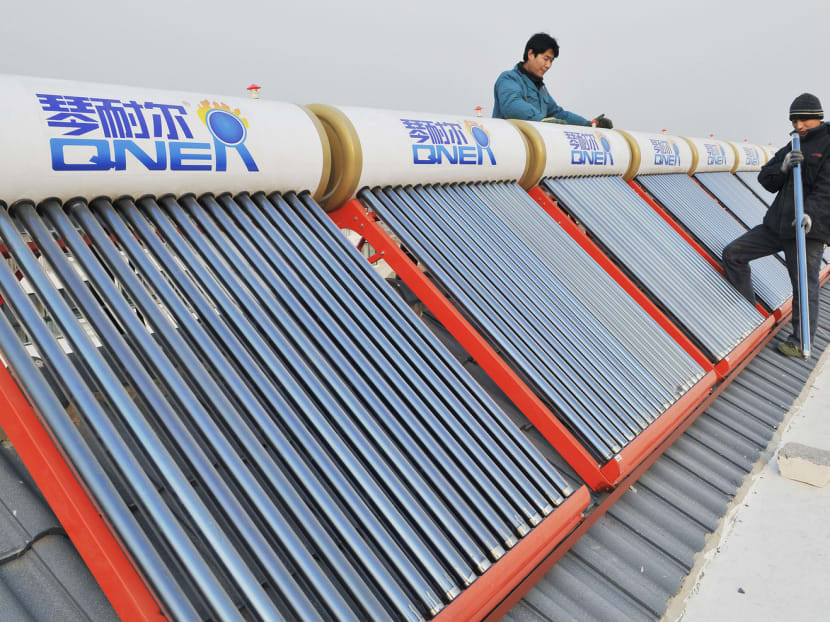

A worker examining solar water heaters on the roof of a residential building in Rizhao, Shandong province. Rooftop solar accounted for just 17 per cent of China’s installed solar capacity in 2014, way below Germany’s 70 per cent. Photo: Reuters

It is a common sight in rural China: Rows and rows of low-rise apartment buildings, often topped by solar water heaters the size of kitchen tables. By one estimate, 30 million Chinese households rely upon the devices for hot water.

They are served by 3,000 companies that sell around one million of the devices annually.

Neither subsidies nor environmental guilt account for the sales, or for China’s place as the renewable hot-water capital of the world.

Folks in rural areas have been buying them for two decades because they are cheap to own and operate.

Ever since United States President Donald Trump announced that the US would withdraw from the Paris climate treaty, there has been a lot of overheated talk about how China would now seize leadership of the global fight against climate change.

It is easy to see why: Chinese leaders face pressure to address rampant pollution, and have the resources to implement massive clean-energy projects, such as the world’s largest floating solar array, launched on a Chinese lake last week.

But if China truly is to lead the world in promoting renewables, it is going to have to think small as well as big. The real opportunity is in pushing innovative greentech — especially the type that fits on a rooftop.

In fact, while China is now the world’s biggest producer of renewable energy, its giant, utility-scale wind and solar installations have started to run up against serious problems.

Thanks to the remote locations needed for such massive projects and the lack of sufficient transmission infrastructure to get the power back to major cities, as much as 17 per cent of all wind power and 20 per cent of all solar power generated in China goes to waste — enough to power Beijing for a year.

The problem has become so acute that in February, China banned the construction of new wind-power projects in six provinces for the rest of the year, lest more wasted capacity be added to the system. Worse, some utility-scale generators are being forced to curb power production.

Moving major wind and solar projects closer to China’s biggest cities is virtually impossible. Given the rapid growth in the size of urban populations and the ensuing sprawl, the vast acreage necessary simply does not exist anymore.

What land is available is far too expensive to justify devoting to windmills. Developers would rather invest in glossy condos.

Yet other opportunities abound. At the end of 2014, for instance, rooftop solar accounted for just 17 per cent of China’s installed solar capacity. In Germany, by contrast, rooftop accounts for at least 70 per cent.

That gap should soon start to close: Bloomberg New Energy Finance forecasts that China will install seven to eight gigawatts of rooftop solar in 2017 — an amount equal to the cumulative installed rooftop solar base up to 2016.

Anywhere but China, that would seem an over-ambitious target.

But the same resources China has brought to bear on megaprojects will help with smaller ones as well. For example, China’s National Energy Administration is piloting a programme in rural areas to boost the incomes of two million poor Chinese, using rooftop solar.

Villagers will become shareholders in cooperatives that manage local power substations and sell any excess power to the grid.

Making the scheme work will require overcoming some steep technical challenges, including developing the infrastructure to transmit energy from often-remote villages to the grid.

Fortunately, State Grid Corporation of China, a power monopoly that dominates 26 of the country’s 32 provinces, has awakened to the business opportunity that rooftop solar presents and is working to make it technically and financially feasible for households and businesses. In April, the company announced the launch of a cloud platform to serve the emerging rooftop market.

It has several components, including an online marketplace in which prospective users can purchase custom turnkey rooftop solar arrays and obtain the financing and subsidies to pay for them. Most critically, State Grid is developing a system to meter and collect payments on behalf of customers with rooftop arrays. That should not be too hard: Nearly 96 per cent of State Grid’s customers already have smart meters.

As China moves forward on planned utility deregulation measures in coming years, those systems will enable peer-to-peer sales of solar power — and further encourage investments in small-scale renewable energy projects.

It cannot happen too soon. China is rapidly urbanising, and each new building offers an opportunity to deepen its commitment to clean energy. If it really wants to be a leader in the fight against climate change, it should start on those roofs. BLOOMBERG

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Adam Minter is an American writer based in Asia, where he covers politics, culture and business. He is the author of Junkyard Planet: Travels in the Billion-Dollar Trash Trade.