The expensive antics of China’s gaudiest billionaire

SHANGHAI — President Xi Jinping’s austerity drive has sent China’s high rollers running for cover, emptying casinos and golf courses as vin ordinaire becomes the new Chateau Lafite. Billionaire art collector Liu Yiqian doesn’t seem to have gotten the memo.

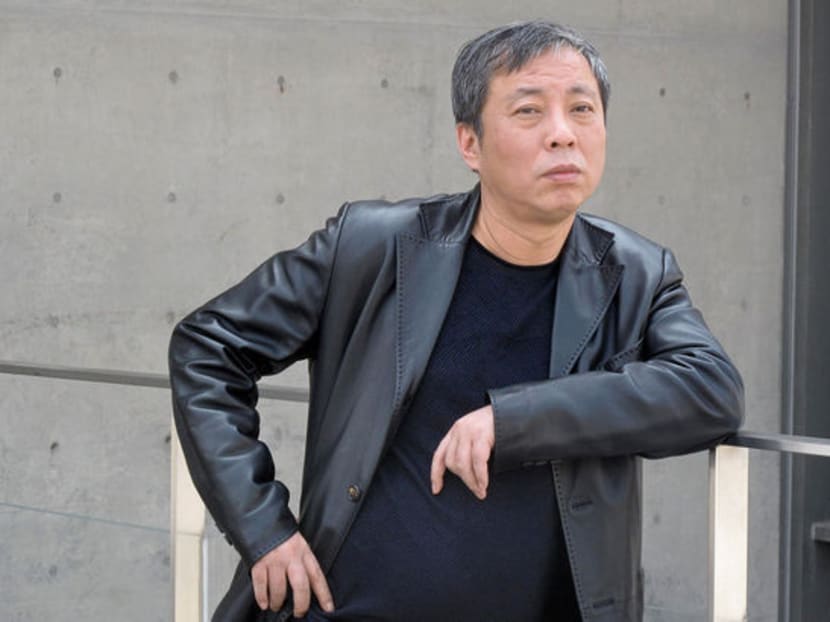

Billionaire art collector Liu Yiqian stands on top of the Long Museum West Bund in Shanghai on March 28, 2015. Photo: Bloomberg

SHANGHAI — President Xi Jinping’s austerity drive has sent China’s high rollers running for cover, emptying casinos and golf courses as vin ordinaire becomes the new Chateau Lafite. Billionaire art collector Liu Yiqian doesn’t seem to have gotten the memo.

The Shanghai-based former taxi driver is on a buying binge that has left rivals gasping at auctions as he outbids all comers for ancient scrolls, Tibetan silk embroideries and imperial porcelain. He’s built and filled two museums with more than 2,300 works, including contemporary pieces by American artist Jeff Koons and Japanese artist and writer Yayoi Kusama. In the past year he’s spent more than US$115 million (S$155 million) picking up such treasures.

Mr Liu, 52, is a classic rags-to-riches story of new China, a high school dropout who made his fortune in the country’s nascent stock trading of the 1980s and ’90s. What sets him apart is the delight he takes in behaving like a Chinese Beverly Hillbilly who has no idea about designer labels (his wife buys his clothes) and still does the grocery shopping when she’s too busy.

In July he caused an online furore in China for drinking tea from a 500-year-old ceramic bowl that once belonged to revered Emperor Qianlong. A photo went viral showing him dressed in a short-sleeved, plaid shirt, with an incipient smirk as he raised the precious, palm-size “Chicken Cup” to his lips.

China’s netizens couldn’t decide which was more outrageous, his treatment of the historic artefact or the record US$36 million he paid for it at a Sotheby’s sale in Hong Kong. Even his settlement for the bowl was theatrical: 24 separate swipes of his American Express Centurion card. He said he didn’t even realise that he qualified for hundreds of millions of reward points.

Conspicuous consumption isn’t new among the billionaires minted during China’s economic boom. But shows of wealth are considerably rarer since Mr Xi came to power in 2012 and began a corruption crackdown that’s netted thousands of officials, some from the top echelons of power. Ten days after Mr Liu’s tea-drinking stunt, the Communist Party said it was investigating former internal security chief Zhou Yongkang.

“I’m not nervous at all, because all my wealth is out in the open and there is nothing to worry about,” Mr Liu says in an interview in one of his Shanghai museums. “Every country has experienced an anti-corruption campaign at some time.”

TIBETAN SILK

As if to prove the point, the AmEx card was out again last month for a Tibetan embroidered silk thangka he’d won for US$45 million at an auction in November.

“In the last year and a half he has asserted himself as the greatest force in the Chinese market,” says Mr Nicolas Chow, deputy chairman of Sotheby’s Asia. “He also has a knack for self-promotion and wild publicity stunts.”

A few days after paying for his thangka, Mr Liu flew with his wife, Ms Wang Wei, and daughter Betty to New York and checked into the St Regis, all on the reward points he’d amassed. He was soon up to his old antics, stripping down to his underwear one night in his room and mimicking the lotus position of an antique Tibetan bronze yogi he was in town to bid for, while Betty captured the moment on her cell phone.

“After Betty took that photo, I thought it was fun and decided to share it,” says Mr Liu, who juxtaposed the image with a photo of the yogi and sent it to friends on Chinese social media service WeChat. “I was holding my breath the whole time,” he says in Chinese as he attempts to demonstrate the pose during the March 28 interview in Shanghai. “It’s really, really hard! You should try it yourself!”

‘CHEEKY CHAPPY’

By the time of the Christie’s auction, the image had been widely shared within the tightly knit Chinese art community. “Most other collectors are quite dull. He’s a cheeky chappy, it’s refreshing,” says London-based art dealer William Qian. “Look at the pictures he posts, how cool is that? He’s a self-made man and can do what he wants.”

As usual, Mr Liu made the winning bid: US$4.9 million.

“When he’s bidding, if he wants it, he gets it,” says James Hennessy, a Hong Kong-based dealer. “That becomes his quest.”

It’s a quest that started 36 years ago, when he dropped out of school at 16 to make leather bags, around the time that Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping was opening the country up and extolling the virtues of being rich.

“Learning at school was useless to me,” says Mr Liu, pointing out how years of wielding shears left his right thumb permanently larger than his left.

Within six years he had saved enough money to buy a taxi, becoming one of the early owner-operators in Shanghai after the state monopoly was dismantled.

His big break came in the late 1980s, when China’s state-owned companies began issuing shares that were often privately traded. Mr Liu says he hit pay dirt in his first trade, buying about 60,000 yuan (S$13,035) of stock at 200 yuan a share in retailer Cheng Huang Miao, now listed on the Shanghai exchange as Shanghai Yuyuan Tourist Mart.

Mr Liu sold his holding when the price soared to 10,000 yuan. “I think I have an exceptional nose for the market,” he says.

FOLLOWING BIDS

As his trading profits grew, Mr Liu started buying art, making up for what he lacked in knowledge by watching other collectors. “Whenever I saw others bidding, I just competed, and after I made the buy I would ask them, ‘Why is this piece good?’”

Today his holding company Sunline Group has a finance unit, a commercial and residential property developer and an insurance arm that has a joint venture with Paris-based AXA SA. He is also the majority shareholder in Hubei Biocause Pharmaceutical. He even has his own auction house, Beijing Council International Auction. Those assets make Liu worth at least US$1.5 billion, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index.

And that doesn’t include his art stash, and Mr Liu says he has no idea how much it’s worth. “It must be a very, very huge figure, but I don’t give it much thought, because I won’t be selling the collection,” says Mr Liu, who dreams of creating a Chinese equivalent of the Guggenheim or the Museum of Modern Art. “I don’t care about the value, nor do I care about the money I spent buying it in the first place.”

That makes him hard to compete with. Earlier this month, seven other bidders at Sotheby’s Hong Kong dropped out as Mr Liu raised the stakes on a southern Song Dynasty vase to more than US$15 million.

PRINCELY CUP

Yet, behind the free-spending, genial image, Mr Liu is still the savvy 16-year-old looking for a new opportunity.

After the Chicken Cup controversy, he commissioned replica versions in three qualities, priced from 288 yuan to 6,900 yuan, generating 5 million yuan in sales so far. He got more publicity out of the bowl, named after the bird images glazed on the outside, by presenting one of the replicas to Britain’s Prince William during a royal visit to the museum on March 3.

He also saves millions of dollars in import tariffs by keeping some of his imported artworks in duty-free zones set up by the government. He gets a temporary import license when he wants to exhibit one of them.

Mr Liu remains unruffled as week by week, more cases of fraud, corruption and tax evasion are announced by the state. Some targets are officials who flouted expensive lifestyles, with Rolex watches, lavish dinners and even Ferraris — acquisitions beyond their official salaries.

Private business owners, who invariably have to deal with state companies and officials, have also mostly scaled back on public displays of wealth, even when, as in Mr Liu’s case, there haven’t been any allegations that it was ill-gotten. In 2012, Mr Liu was investigated as part of a nationwide probe into tax evasion connected with art imports, but wasn’t charged or fined, according to Ms Zoe Zhu, head of public relations at his museum.

It doesn’t hurt that he enjoys excellent relations with the Shanghai municipal government, which sold him subsidised land in order to build his second art repository, Long Museum West Bund, which opened last year.

It may also help that Chinese authorities and the public have tended to be supportive of collectors like Mr Liu who spend millions on repatriating cultural artifacts from abroad. Thousands of sculptures, Imperial ceramics and jade carvings were looted by foreign troops, or removed to Taiwan and Hong Kong by Chinese fleeing the communists during the last century.

And for all the ire generated by Mr Liu’s irreverence, for many, he still represents a Chinese ideal, the self-made man who hasn’t forgotten his roots.

“I never felt that my wealth has risen to a level that makes me no longer a normal person,” Mr Liu says over a box lunch of rice, vegetables and pork cutlet at the museum. “If buying a cup and drinking tea makes one nouveau riche, and opening a museum makes one a gentleman, it would be too easy to differentiate one from the other. You shouldn’t care what people call you.” BLOOMBERG