How China bought its way into Cambodia

BEIJING — In Cambodia’s Chinese business community, “Big Brother Fu” is a name to be reckoned with. A former officer in China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA), his thickset build and parade-ground voice reinforce the authority suggested by his nickname. But his physical bearing pales next to the heft of his political connections. Few, if any, foreign investors in this small but strategically important South-east Asian nation enjoy access as favoured as that of Mr Fu Xianting.

BEIJING — In Cambodia’s Chinese business community, “Big Brother Fu” is a name to be reckoned with. A former officer in China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA), his thickset build and parade-ground voice reinforce the authority suggested by his nickname. But his physical bearing pales next to the heft of his political connections. Few, if any, foreign investors in this small but strategically important South-east Asian nation enjoy access as favoured as that of Mr Fu Xianting.

At state events, Mr Fu wears an official red sash studded with gold insignia, attire that hints at his ties to Mr Hun Sen, Cambodia’s authoritarian ruler. So close is Mr Fu to the Prime Minister that the leader of his personal bodyguard unit, some of whose members have been convicted of savage assaults on opposition lawmakers, calls him “a brother” and has pledged to “create a safe passage for all of Mr Fu’s endeavours”.

These connections have helped Mr Fu and his company, Unite International, win a rare concession to develop one of the most beautiful stretches of Cambodia’s coastline into a US$5.7 billion (S$7.7 billion) tourist destination. More broadly, they signal how big money, secret dealings and high-level backing from China’s Communist Party have helped pull Phnom Penh firmly into Beijing’s sphere of influence.

As China has sought to assert its authority in the South China Sea, some South-east Asian nations have bolstered their ties with the United States, including Vietnam and the Philippines. Cambodia is China’s staunchest counterweight, giving the country of 15 million people an outsized role in one of the world’s most fraught geopolitical tussles.

With an effective veto in the Association of South-east Asian Nations (Asean), the region’s top diplomatic grouping, Cambodia has a weapon to wield on China’s behalf.

Mr Fu’s story shows how private Chinese companies, backed by Beijing’s diplomatic resources and the unrivalled muscle of its state-run banks, are spearheading a commercial engagement that helps form the foundation for China’s political and strategic ambitions.

“In terms of money, China is the number one,” said Mr Phay Siphan, a Secretary of State within Cambodia’s Council of Ministers. “The power of China is getting much bigger ... we choose China because (its investment) does not come with conditions. A number of Western investments come with attachments. (They say) we have to be good in democracy. We have to be good in human rights. But in Cambodia we went through a civil war and we understand that if you have no food in your stomach, you cannot have human rights.”

An investigation by the Financial Times (FT) reveals the favoured treatment Chinese companies have won from Cambodia’s leadership, resulting in the award of land that far exceeded legal size limits, the apparent overriding of a state decree for the benefit of a Chinese investor and official support against the protests of dispossessed farmers.

An analysis of state documents shows that in several cases, Chinese investments were facilitated personally by Mr Hun Sen, a ruler of 31 years who insists on being referred to as “Lord Prime Minister and Supreme Military Commander”.

Global Witness, the United Kingdom campaign group, claimed in a report this year that the Cambodian leader presides over a “huge network of secret dealmaking and nepotism” that has allowed his family to amass stakes in leading industries and help “secure the Prime Minister’s political fortress”.

Cambodia’s government has accused Global Witness of having an agenda and refused to comment on its allegations. Mr Phay Siphan did not reply to phone calls and emails about the Global Witness report.

Mr Hun Sen’s personal assistance was crucial in providing Mr Fu, 67, with his early break. A letter written in October 2009 by the Prime Minister wishes Mr Fu “complete success” in developing a 33sqkm area of coastal land on a 99-year lease — even though some of the land fell within a protected national park. The Prime Minister also set up a special committee with representatives from seven ministries to assist with the project’s execution.

“I express my personal thanks and support for your company to carry out this tourism project,” wrote Mr Hun Sen in the letter, seen by the FT. It is dated nine months after Mr Fu’s company donated 220 motorbikes to Mr Hun Sen’s bodyguard unit, a 3,000-strong private army equipped with armoured personnel carriers, missile launchers and Chinese-made machine guns. The gift was the latest in a series of donations to the unit, which is charged with guarding the Prime Minister and his wife Bun Rany, officially known as the “Most Glorious and Upright Person of Genius”.

‘OUR BROTHER OF MANY YEARS’

In an account of the ceremony at which the motorbikes were presented — published on the Chinese company’s website — Mr Sok An, a Deputy Prime Minister, was quoted as “thanking the Unite Group for this gift of 220 motorbikes and several previous donations of material assistance to Hun Sen’s bodyguard … which have fulfilled the duty of donation to the royal government”.

Unite formed a “military-commercial alliance” with the bodyguard unit in April 2010, a highly unusual arrangement for a foreign company in Cambodia. At a ceremony to celebrate the alliance, Lieutenant General Hing Bunheang, commander of the bodyguards and one of Mr Hun Sen’s closest associates, showered praise on Mr Fu. “Mr Fu is our brother of many years who has made an outstanding contribution to the development of Cambodia,” Lt Gen Hing Bunheang is heard saying on a video, according to a Chinese voiceover. “Mr Fu’s business is our business. We will create a safe passage for all of Mr Fu’s endeavours.”

Such accolades represented a high point in Mr Fu’s business career, which has seen him move from at least a decade in the PLA to manager and chairman of Chinese state-owned enterprises, say company documents. His dealings in Cambodia began in the early 1990s when he organised an exhibition of Chinese agricultural machinery. He holds a position in Beijing on a committee of the China Association of International Friendly Contact, which reports to the Foreign Ministry. But his business profile inside China appears almost nonexistent, with corporate databases showing only a role as “legal representative” of Beijing Tian Yi Hua Sheng Technology, a company with just two million yuan (S$406,364) in registered capital.

In Phnom Penh, though, Mr Fu is probably China’s most influential businessperson, an official adviser to Mr Hun Sen and the recipient of state and military honours. But notwithstanding these gold-plated connections, Mr Fu’s investment in Cambodia has proven controversial.

Environmental groups protested that the Chinese company had been able to secure land inside the Ream National Park, which was protected from development under a royal decree. Licadho, a Cambodian human rights group, complained that hundreds of farming families were evicted from their homes. Villagers staged protests to hamper the Chinese company’s work. In May 2010, a decree from the Council of Ministers revoked licences held by Mr Fu’s company for the development of the Golden Silver Gulf, the name of his proposed resort, according to a copy of the decree obtained by the FT. The document passed responsibility for the area over to the Environment Ministry, but it remains unclear whether development work was ever actually halted.

Contacted by phone and email, Mr Fu declined to comment on the decree revoking his licences but said the approvals he won from Mr Hun Sen’s government had been secured because of his reputation as a trusted businessman in Cambodia and had nothing to do with his “military-commercial alliance” with the bodyguard unit.

This year, a subsidiary of Unite International, Yeejia Tourism, announced several deals relating to the project, signalling a resumption of activity.

WARMING SINO-CAMBODIA TIES

Mr Hun Sen has not always been pro-China. He once labelled it the “root of everything that is evil” because of Beijing’s support for the genocidal Khmer Rouge, which killed an estimated 1.7 million Cambodians in the 1970s.

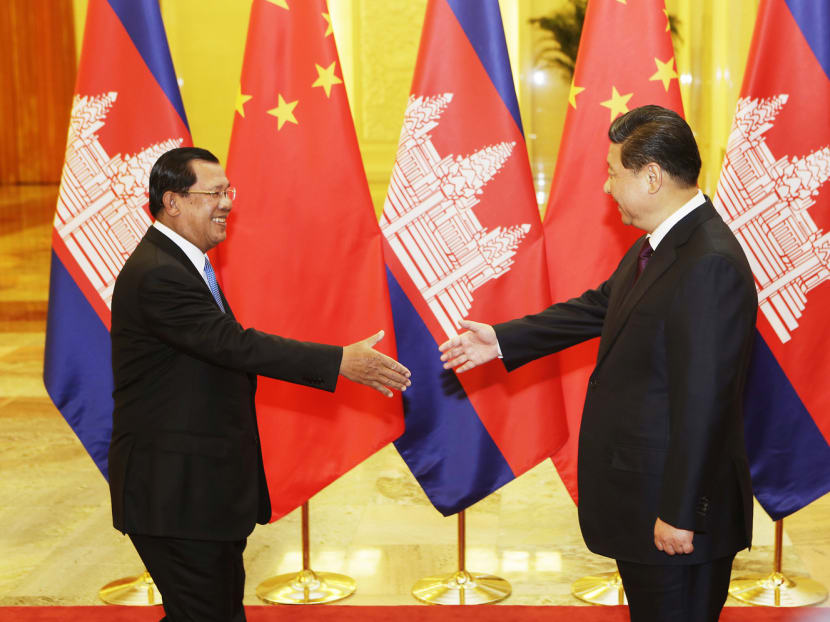

But during the past 15 years, the Cambodian leader has become China’s most reliable supporter in South-east Asia, presiding over the sale of his country’s top assets to Chinese companies, forging military links and praising Beijing as a “most trustworthy friend”.

This elevation of China has at times translated into a cold shoulder to the US, as President Barack Obama found during an East Asia summit in Phnom Penh in 2012. As the first sitting US president to visit Cambodia approached the government building, he saw two banners proclaiming: “Long Live the People’s Republic of China”.

In the 20 years from 1992, when the West started to engage in building democracy in Cambodia, donor nations delivered some US$12 billion in loans and grants — a large portion of which was never spent on development but went instead to pay the salaries of expensive consultants, according to Mr Sebastian Strangio, author of Hun Sen’s Cambodia. By contrast, China invested US$9.6 billion in the decade to 2013; and about a further US$13 billion is yet to come, according to the Cambodian Institute for Cooperation and Peace, a think-tank.

But China’s magnetism is not confined to its investment firepower. Chinese companies, backed by the China Development Bank and other powerful institutions, have a reputation for delivering crucial infrastructure projects quickly and without delays caused by human rights and environmental objections.

An example is the US$800 million Lower Sesan 2 dam being built by HydroLancang, a state-owned Chinese company. The 400mw dam has been hit by protests from thousands of villagers who are set to be displaced or lose their livelihoods, but it remains on schedule for completion in 2019.

Of some 8 million hectares (80,000sqkm) granted to companies between 1994 and 2012, nearly 60 per cent or 4.6 million ha — an area larger than the Netherlands — went to Chinese interests, according to estimates by the Cambodia Centre for Human Rights, a group funded mostly by Western donors.

A blend of secrecy and elite contacts is evident in two other large Chinese investments that were enabled by Mr Hun Sen and his executive, according to copies of the decrees. One involved a 360sqkm land concession for a US$3.8 billion investment by Union Development Group, a subsidiary of the Wanlong Group, a large Chinese developer. The other was a 430sqkm concession for a US$1 billion investment by Hengfu Sugar, one of China’s largest sugar producers. The combined size of these concessions is larger than Phnom Penh, the capital.

Both investments have triggered waves of protests by farmers and both exceeded the 100sqkm legal limit on concessions to a single company. Hengfu Sugar skirted this law by setting up five separate companies to each receive a contiguous land concession slightly smaller than the limit, according to concession documents.

Although each of the five companies carries a different name — Heng Rui, Heng Yue, Heng Non, Rui Feng and Lan Feng — company executives acknowledged they are in fact all owned by Hengfu Sugar. Mr Tan Jiangxia, the company’s representative on the plantation in the central province of Preah Vihear, explained how the company avoided the restriction: “This is related to a clause in the land concession law. One company is only allowed to get hold of 10,000ha or less, so we have kept the land under each company at under 10,000ha.”

Big investment deals have cemented Beijing’s relations with Phnom Penh, but they have also helped yield political dividends for China as it imposes claims to disputed areas in the South China Sea.

With US destroyers sailing close to Chinese-built islands equipped with anti-ship missiles, the South China Sea has become one of the world’s most highly charged flashpoints.

As regional tensions have grown, so has Cambodia’s value to Beijing. Of particular use is Phnom Penh’s membership in Asean. Because Asean works by consensus, the objections of one member can thwart any group initiative. Cambodia used this effective veto to protect China in July. Asean was poised to issue an official statement mentioning an international tribunal’s ruling that there was no basis under UN law for China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea. But after Cambodia objected, a watered-down final communique was issued with no mention of the ruling.

China, which had pledged US$600 million in aid for Phnom Penh just days before the Asean meeting, reacted with public delight. Mr Wang Yi, the Foreign Minister, said Beijing “highly appreciates” Cambodia’s stand in the meeting, which history would show was “correct”. A few days after the meeting, Beijing said it would build a US$16 million National Assembly hall in Phnom Penh.

“Since the ruling against China of the (international) tribunal in July, China has offered Cambodia US$600 million in aid and in return Cambodia has at least twice blocked Asean statements criticising China,” said Mr Murray Hiebert, South-east Asia expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, an American think-tank. “Cambodia gets a lot in return. It gets foreign aid, it gets debt forgiveness and for a government that is very dependent on foreign aid, it gets critical Chinese aid. And the Chinese don’t ask questions on human rights.” FINANCIAL TIMES