President Xi takes Mao’s space dream from Gobi Desert into next frontier

BEIJING — Jiayuguan was once the tangible edge of Chinese civilisation — where the Great Wall ends and the desolation of the Gobi Desert begins.

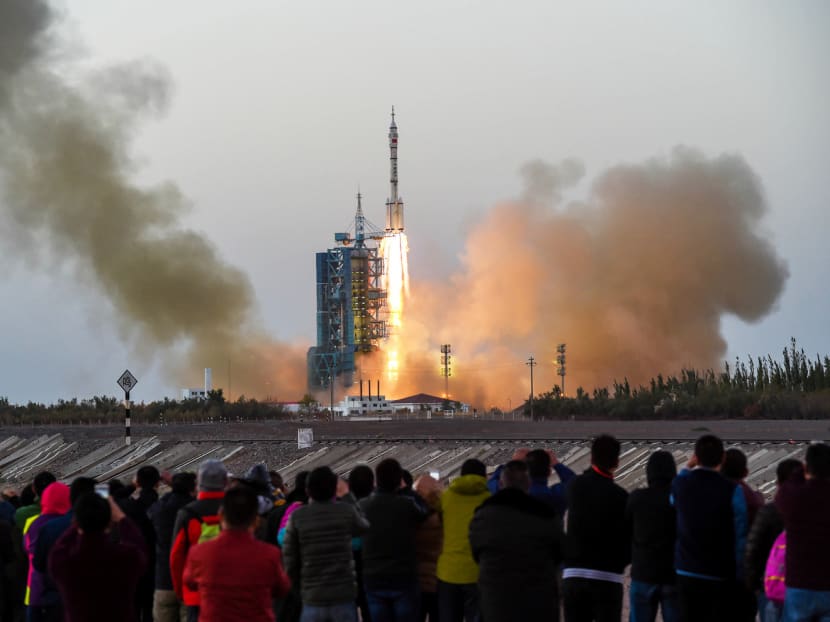

Visitors watching the Shenzhou 11 manned spacecraft carrying astronauts Jing Haipeng and Chen Dong blast off in Jiuquan last month. Photo: Reuters

BEIJING — Jiayuguan was once the tangible edge of Chinese civilisation — where the Great Wall ends and the desolation of the Gobi Desert begins.

Now, four hours beyond those limits in a locked-down location along the Ruoshui River, China has built a gateway to the new final frontier.

Jiuquan Satellite Launch Centre is the nation’s pre-eminent “space city” — one of only three places where humans are blasted into the cosmos.

Six manned flights have departed from here, including last month’s Shenzhou 11 mission to China’s own orbiting lab. Manned trips to the moon and Mars in the next decades also are being discussed.

The centre is also the launching place for China’s most-important machines. The world’s first quantum-communications satellite, designed to provide hack-proof transmissions for the military, left here in August. The government and military, which ultimately controls the space programme, do not announce every launch, but the non-profit Space Foundation estimates that at least 82 attempts have been made from the site since 1970.

Foreign media typically are not allowed near the launchpad. Authorities made a tightly controlled exception for the Shenzhou 11 blast-off, providing a rare opportunity to visit the oasis-like city, which rises from a moonscape reminiscent of the remote United States Air Force facility in Nevada known as Area 51.

Schedules for visiting the administrative centre were organised to the minute, with government minders warning that wanderers would be locked up by the military in places where even they could not help.

Planning for a launch centre began in 1956 as part of Mao Zedong’s ambition to match the rocketry prowess of the Soviet Union and the US. China’s first order of business was developing intercontinental ballistic missiles, and the base was built in 1958.

Operations are so sensitive that minders, professors and several government officials contacted by Bloomberg News said they would not answer any questions about the location.

From Jiayuguan, a thin, black artery of tarmac winds north-east through boundless stretches of rock and grit before arriving at the centre, which is deliberately misnamed and lies within Inner Mongolia.

At a final checkpoint guarded by troops in woodland camouflage, the razor wire-topped fences part and urban life sprouts. Wide, fastidiously clean avenues lined with leafy trees meander around lakes and grassy knolls dotted with disused rockets that serve as sculptures and backdrops for selfie-taking, government-approved tourists.

The space facility is nominally a military base attached to the People’s Liberation Army Air Force. Soldiers armed with wicker broomsticks march briskly to their stations to wage a futile war against the blowing sand.

Images of President Xi Jinping are ubiquitous here. Billboards show him with his hands frozen in a silent clap to congratulate a successful lift-off.

“Exploring the vastness of the universe, developing the space industry and constructing space power is our unceasing pursuit of the space dream!” one caption reads.

The pedestrian touchstones of modern China are ever-present. Traffic cops and speed cameras watch for law-breaking drivers, and black sedans with visiting dignitaries line up at the petrol station. Miniature replicas of Chinese-designed Long March rockets are sold next to cigarettes and chewing gum.

Questions faxed to the State Council Information Office about the community went unanswered. After a trip to cover the Shenzhou 8 mission in 2011, the state-run Nanfang Daily newspaper reported that about 35,000 people live in the residential zone of the centre, which spans 2,800sq km — an area more than twice the size of Los Angeles. Most are connected to the space programme, either as employees or workers serving them.

At lunchtime, residents on electric scooters ferry goods and children via streets lined with cream-coloured office blocks, apartment buildings, eateries and primary schools with murals on their walls. Look carefully and reminders of space abound, like the yogurt sold in a cafeteria which comes in tubs stamped with cartoon rockets lifting off above an ocean of milk.

Some of the people overseeing the launch centre are the sons and daughters of those who arrived under Mao. They typically study at Zhejiang University or the National University of Defense Technology.

Minders shooed foreign journalists away from the locals, but the state-run Xinhua News Agency reported in September that the biggest challenge for many residents was exposing their children to civilisation outside the tiny, isolated town.

“This is the Gobi Desert — desolate and lonely — but long ago, we turned this into home,” Yu Ling, a resident who grew up in Heilongjiang province, near Russia, told Xinhua. “Before, I came crying, but now I’m reluctant to leave.” BLOOMBERG