S China Sea ruling: Turning point in Chinese foreign policy?

China’s posture and reactions towards the Philippines versus China arbitration over the South China Sea dispute unsurprisingly reflected its prior positions: Non-participation, non-recognition, non-acceptance and non-compliance.

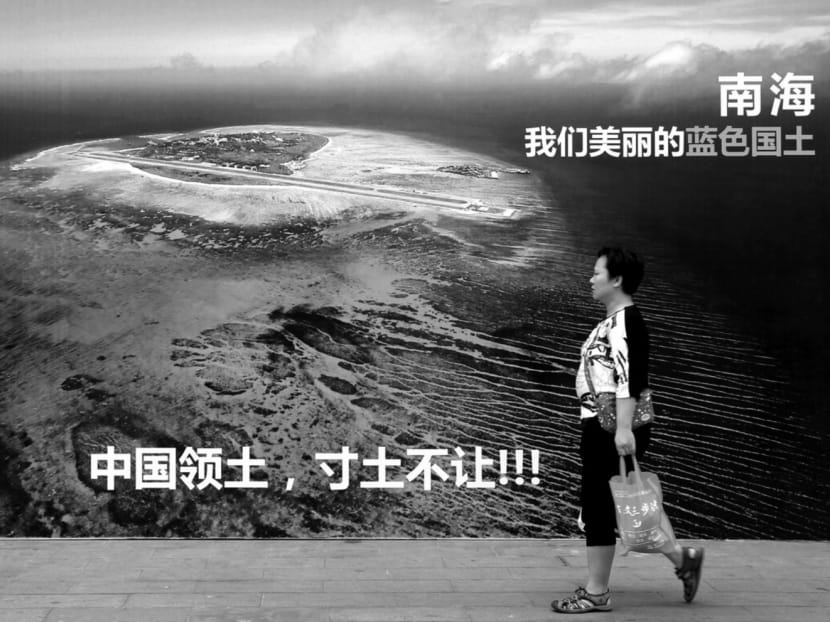

A billboard with an image of an island in South China Sea with Chinese words that read: ‘South China Sea, our beautiful motherland, we won’t let go an inch’ in China’s Shandong province. China needs to assess the harm the disputes over South China Sea is doing to its strategic and security interests in the last few years. PHOTO: AP

China’s posture and reactions towards the Philippines versus China arbitration over the South China Sea dispute unsurprisingly reflected its prior positions: Non-participation, non-recognition, non-acceptance and non-compliance.

The tension and diplomatic jostling among various parties in the past few years have resulted in dramatic internationalisation of the South China Sea issue and compelled China to devote a lot of resources to deal with the negative impact on China’s interests.

The arbitration has significantly increased the salience of the South China Sea issue in China’s international relations and is likely to be a turning point in China’s foreign policy.

For decades, Beijing has had to ferociously contend with various players in its external relations over the so-called three “Ts” issues: Taiwan, Tibet and Trade.

It spared no efforts to defend the “One China” principle, counter endless human rights criticisms from the West, and deal with trade disputes with many developed countries.

However, in the past decade or so, China has managed to cope with these challenges. Taiwan’s independence, international pressure on human rights and trade-related disputes are certainly still major concerns for the Chinese foreign policy elites but no longer as threatening to China as they used to be.

One can even make the argument that these issues are gradually losing salience in China’s foreign relations as Chinese decision-makers now possess more policy options as a result of the growth of Chinese power and Beijing becoming more experienced in handling the three “Ts”.

It may be the case that the reduced pressure from the three major challenges has made it possible for Beijing to adopt a more heavy-handed approach when dealing with territorial and maritime disputes in the East and South China Seas in recent years.

Sources of tension and dispute in the South China Sea in the past few years have been multiple, for instance other claimants’ actions and entanglements with external powers.

But many analysts would believe that Beijing’s overreaction and policy moves to change the status quo in the South China Sea to China’s favour have also contributed to the vicious cycle of developments in the dispute.

Whether Beijing likes it or not, the South China Sea disputes have collectively become a new major issue that is increasingly generating a profound impact on China’s foreign relations far beyond Beijing’s already complicated relationships in the Asia-Pacific region.

The July 12, 2016, ruling, widely seen as a game changer in the disputes, is likely to lead to the emergence of a fourth “T” in Chinese foreign relations: Territorial (and maritime) disputes in the South China Sea.

It is in this sense that one may regard the arbitration and more broadly, the South China Sea issue as a turning point in Chinese foreign policy. Beijing’s own efforts in trying to win symbolic diplomatic support from more than 60 countries in the world before and after the arbitration attest to this observation.

WHY A TURNING POINT

There are good reasons to believe why such a turning point may already be on the horizon.

Firstly, the validity and functionality of the arbitration are likely to be a major source of friction between Beijing and some parties in the years to come. Beijing may hope to wish away the arbitration ruling and regard it as nonexistent.

But judging from the various statements by key countries and what has been happening recently at various international institutions such as the G7, Asem (Asia-Europe Meeting), Asean (Association of South-east Asian Nations)-related meetings, and a few Track II events, it is almost certain that much of the international community will not easily give up the arbitration result as a policy tool in dealing with China vis-a-vis the South China Sea disputes.

In contrast to the external expectations, it is also almost certain that China will continue to be intransigent in dealing with the South China Sea dispute and the arbitration.

Chinese media have kept lambasting other claimant countries and external powers, particularly the United States and to a lesser extent Japan, for stirring up trouble in the South China Sea.

Secondly, any future conflict in the South China Sea will inevitably be linked to and scrutinised through the arbitration ruling. For now, we do not see any clear sign that either China itself or all the relevant parties together have any grand policy to effectively prevent conflict from arising.

Popular nationalism in China further rose in the wake of the arbitration. Chinese elites seem to genuinely believe that Washington has been behind all the problems that Beijing faces in the South China Sea. Many Chinese policy analysts tend to subscribe to the idea that the growth of Chinese power will ultimately help resolve the dispute.

A minority Chinese view that favours a more moderate policy line is either suppressed or self-censored because of the overwhelming socio-political pressure in Chinese society and policy circles.

In some cases, even attempts to objectively analyse the arbitration have been labelled as unpatriotic.

There is now a growing awareness in China that Beijing should pay more attention to the legal aspects of the South China Sea disputes but it is unclear whether the legal profession could play a larger role in the nation’s decision-making any time soon.

Thirdly, the contrasting views and policy differences between China and many other players in the South China Sea issue may appear increasingly glaring as many political leaders in the region are keen to emphasise the importance of rules in managing disputes and regional affairs.

In general, China does not seem to oppose a rules-based regional order but it feels uneasy about the fact that many existing rules and norms had been created in the context of American predominance in the region.

Beijing is also cognisant that the rules other parties may want to apply in the South China Sea run against China’s objectives in the dispute.

This contention over rules in the regional maritime domain may have wider repercussions in China’s foreign relations.

With the rapid rise of China, the international community is anxiously watching how the resurgent global power will maintain or change the existing international rules. The South China Sea is increasingly becoming a litmus test for China in this regard.

FUTURE TRAJECTORY: POWER SPEAKS?

The arbitration is unlikely to help soften China’s position and policy in the South China Sea. The “ever since ancient times” narrative, the deeply-rooted sense of legitimate interests and rights in the South China Sea, and the growing inclination in the Chinese policy circle towards the utility of power suggest that Beijing may, by and large, continue to follow its own policy trajectory, in disregard of the arbitration and concerns of other parties.

Regional and extra-regional players will, of course, constantly try to rein in China’s behaviour and push back when necessary, even though they may not be successful each time.

The end result is that the South China Sea issue continues to serve as a major challenge in China’s neighbourhood diplomacy and a new major issue in its general foreign policy.

Chinese decision-makers would be wise to more thoroughly assess the harm that the South China Sea disputes have done to Beijing’s regional strategic and security interests in the past few years.

Leaders in Beijing have choices to make as to how much power they could employ in handling the disputes and what can be done to significantly mitigate the negative ramifications of the disputes in China’s foreign relations.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Li Mingjiang is Associate Professor and Coordinator of the China Programme at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. This piece first appeared in RSIS Commentary.