Modi’s four big hurdles in mission to modernise India

Whatever they think of Mr Narendra Modi’s views on religion and politics, there are scarcely any Indians who do not support his mission to turn the country into an industrial power.

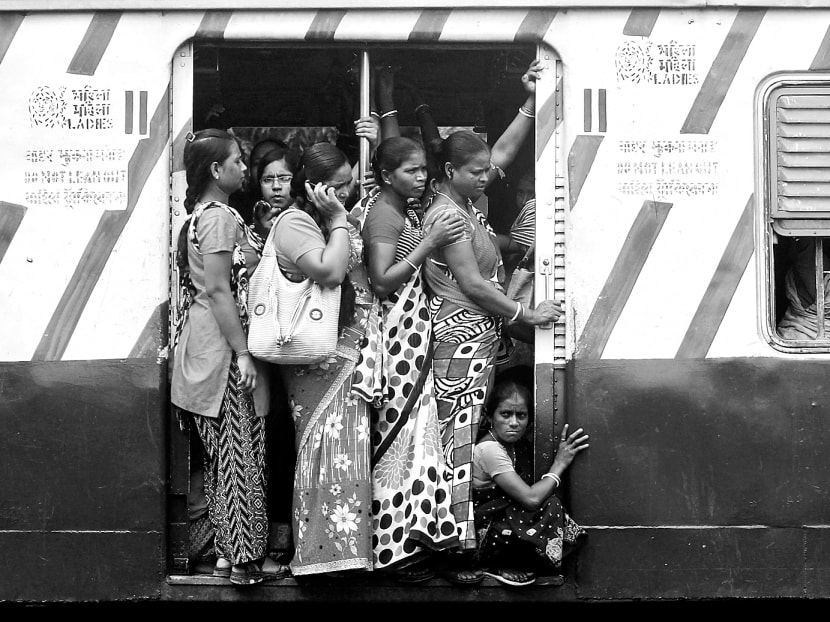

Commuters on a rush-hour train in Kolkata. One of Mr Modi’s problems is a crippling deficit in transport and power infrastructure. Photo: Reuters

Whatever they think of Mr Narendra Modi’s views on religion and politics, there are scarcely any Indians who do not support his mission to turn the country into an industrial power.

The Prime Minister of India, however, must overcome four big obstacles if he is ever to achieve his aim of creating millions of jobs and increasing the share of manufacturing in gross domestic product from 15 per cent to 25 per cent.

His first problem — an inherited one — is a crippling deficit in transport and power infrastructure estimated by the previous government to need US$1 trillion (S$1.27 trillion) of new investment. Even with economic growth running at a modest 5 per cent a year, Indian railways, roads, ports and airports are clogged by high traffic volumes and poor management.

As usual in the busy festive season of the Indian autumn, thousands of containers of goods are waiting to move from northern to the west coast ports for export, while a further 40,000 to 50,000 containers of imports are stuck near the docks for lack of rail capacity to bring them inland. The crunch has been worsened by the need to import millions of tonnes of extra coal because of the incompetence of state-owned Coal India and regulatory disputes with private miners.

WINNING OVER INVESTORS

Mr Modi’s second challenge is investors’ lack of faith in the ability or will of Indian governments and regulators to maintain consistent policies and adhere to their contractual obligations.

At least, as one industrialist put it, “profit is no longer a dirty word”, as it was under previous governments of the left-leaning Congress party. But the Modi administration has shied away from reversing billions of dollars of retroactive tax demands that alarmed big investors such as Britain’s Vodafone. It has cancelled an agreement on world trade and repeatedly postponed implementation of an agreed rise in the price paid to producers of Indian natural gas.

Dr Rajat Kathuria, who heads the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations, says the administration needs to overcome “a very large trust deficit between government and the private sector”.

It is not just the government. In its latest interventionist ruling, the Supreme Court has ruled illegal the allocation of 214 of the 218 coal mining blocks allocated since 1993, throwing steel and power companies into confusion with what Dr Surjit Bhalla, chairman of Oxus Investments, calls “the mother of all retrospective laws” dating back three decades.

Mr Modi’s third problem, again inherited, is the people’s poor schooling. Dr Ashoka Mody, a United States-based economist sceptical about the chances of an Indian industrial miracle, says the country has barely invested in education and has been easily overtaken by rivals such as Vietnam.

Even Mr Modi’s critics accept that he is trying to overcome these obstacles. On infrastructure, the Prime Minister says the railways need billions of dollars of investment, while transport consultants expect the government to award contracts for 10,000km of new roads by January.

As for regulation, Mr Modi said on his recent visit to the US that he was convinced of the importance of “tax stability” and regarded the court’s coal ruling as a chance to “clean up the past” and move forward. On education, he has talked repeatedly of investing in schools and skills.

The fourth problem lies in the quality of his own government and the way decision-making for a country of 1.3 billion people is highly centralised in the Prime Minister’s office. Mr Modi still inspires confidence in the world of business. “Add it all up and I think the foreign investors should be bloody happy,” says Dr Bhalla.

But there is a dawning awareness that Mr Modi will need all his energy and political skill if he is to even begin transforming India into a modern industrial nation by the end of his five-year term. As one Indian hotelier put it: “It’s really now or never for India.” THE FINANCIAL TIMES

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Victor Mallet is the Financial Times’ South Asia bureau chief.