America faces its iceberg of inequality, debt

Inequality and debt are pushing the United States towards a deadly spiral promising a slow and painful end game, precisely at a moment when the world needs a revival and confidence, as do the Americans.

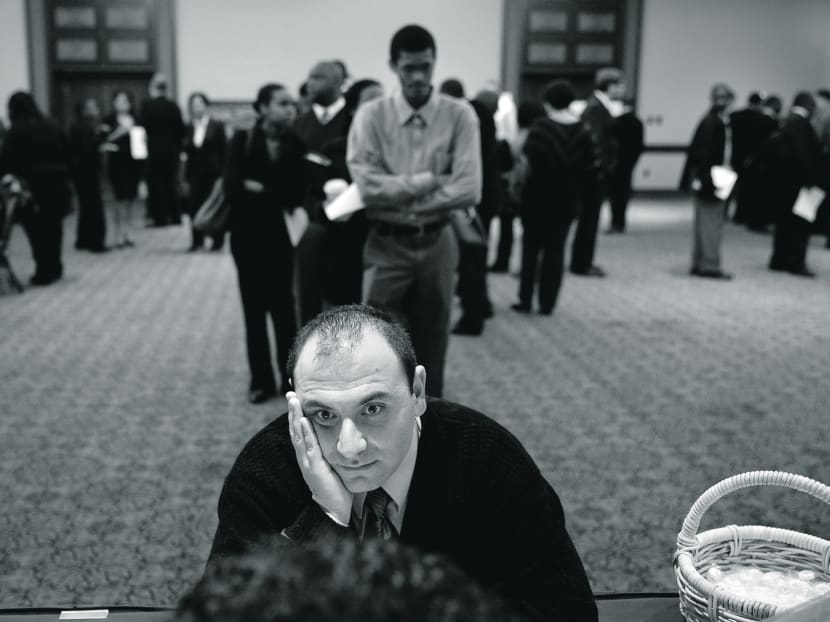

Job-seekers at a US career fair. A study found that 42 per cent of American men raised in the bottom fifth of incomes stay there as adults. Photo: Bloomberg

Inequality and debt are pushing the United States towards a deadly spiral promising a slow and painful end game, precisely at a moment when the world needs a revival and confidence, as do the Americans.

Over the recent months of recovery, US incomes grew 1.7 per cent. This figure looks good at first, but belies an earnings rise for the top 1 per cent of 11.2 per cent, with a decline of 0.4 per cent for 99 per cent of Americans.

Excluding earnings from investment gains, the top 10 per cent accounted for 46.5 per cent of all income in 2011 — a proportion not seen since 1917. The number of Americans in poverty jumped to 15.1 per cent (about 46.2 million people) in 2010, a 27-year high.

Total debt (all sectors included) amounts to approximately 400 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP). US sovereign debt is around 100 per cent of GDP, with the federal deficit for fiscal 2013 forecast to be 5.3 per cent. After a brief respite over the next three to four years, it will go up again.

This could go on for a while, no one knows for how long, but not indefinitely. When the trap snaps, there will be no way around the awkward political dilemma of who is going to pay for the debt, necessitating burden sharing among groups and consequently agonising choices.

THREE POSSIBLE DESTINIES

At the end of the 18th century, a number of European nations faced a situation not totally but largely similar to the one we see today in America.

The French political system over several centuries allowed those who had the money (the aristocracy and to a certain extent the church) to stay out of reach of the King’s revenue collections to finance the functions of the state.

As these groups exempted themselves from any genuine taxation, an increasingly heavy burden was put on those who had very little to spare — ordinary citizens — pushing them to react against a political system not offering them any protection from exploitation (in fact, some in the system even joined the group of predators).

Britain avoided a similar outcome due to the industrial revolution, a growing class of merchants and a less powerful aristocracy than in France.

The two Scandinavian countries in those days, Denmark–Norway and Sweden, saw the King ally himself with the peasantry, further weakening an already declining aristocracy. This paved the way for the Nordic societies we see today, with high equality — economically as well as socially and culturally — and social mobility. The elite’s already-reduced powers to defend their privileges, of which not many were left, were curbed, lowering barriers for social mobility.

The question looming for the US is which way to choose. France (tax the poor, exempt the rich), Britain (gamble on a strong economic recovery, even if nowhere in sight), or the Nordic countries (break the back of the privileged)?

DECLINING MOBILITY

So far, the omens are not good. Much has been written about the dysfunctional nature of the US political system and, so far, it has lived up to this reputation.

The US economy and its ability to forge ahead in technology and innovation have not come to a standstill — yet.

The writing on the wall, however, is becoming bigger and more visible. One by one the country’s trump cards seem in danger — namely social and geographic mobility, Americans’ innovative ability, meritocracy and mobilisation of talent through the education system.

Geographical mobility used to be one of the real strengths of the US economy. People moved to where the jobs were, keeping the economy humming. Not so anymore. Twenty years ago, one in five workers moved geographically every year; recent figures show it is down to one in 10.

A number of studies point unequivocally to falling social mobility. One of the studies found that 42 per cent of American men raised in the bottom fifth of incomes stay there as adults, compared to Denmark with 25 per cent and Britain 30 per cent. Just 8 per cent of American men at the bottom rose to the top fifth — compared to 14 per cent of the Danes and 12 per cent of the British.

Despite the label of “classless society”, about 62 per cent of Americans raised in the top fifth of incomes stay there; 65 per cent born in the bottom fifth stay in the bottom two-fifths.

The American elite are doing too well at passing on privileges down to the next generation, with social mobility a victim. This is reflected by how much a father’s relative income influences that of his son (in this, the US is at about the same level as Britain and Italy, but far less progressive than the Nordic countries).

TICKING TIME BOMBS

The number of patents filed by American companies is now increasingly due to foreign nationals living in the US. Just to cite some US corporate icons, for General Electric the foreigner-share of patents is 64 per cent; for Merck 65 per cent; and for Cisco 60 per cent.

Foreigners living and working in the US may not be there permanently; they may be lured away by offers from their home countries or other countries.

Another ticking time bomb that could undermine America’s future capability in technology and innovation is the cost of higher education.

Some 57 per cent of Americans take the view that higher education is not worth the money and 75 per cent says it is too expensive for most Americans. A large share of students after finishing education move in with their parents, for the simple reason that they cannot afford to pay rent as they need to pay back study loans. A side effect of this is obviously lower geographical mobility.

Debt-inequality thus constitutes a barrier for what used to be the American enterprise system. The problems measured in money terms are not insurmountable, far from it — but unless the political system manages to take action, the prospect of a parallel destiny to what happened in France more than 200 years ago becomes very real indeed.

Joergen Oerstroem Moeller is a Visiting Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore; and an Adjunct Professor with the Singapore Management University and Copenhagen Business School.