BN’s manifesto rides on material gains and patronism

The BN manifesto outdoes its predecessors in heft and gloss but reverts to the habitual formula of reminding people of material gains delivered, persuading voters that only it can do the job. Question is, do voters still buy it?

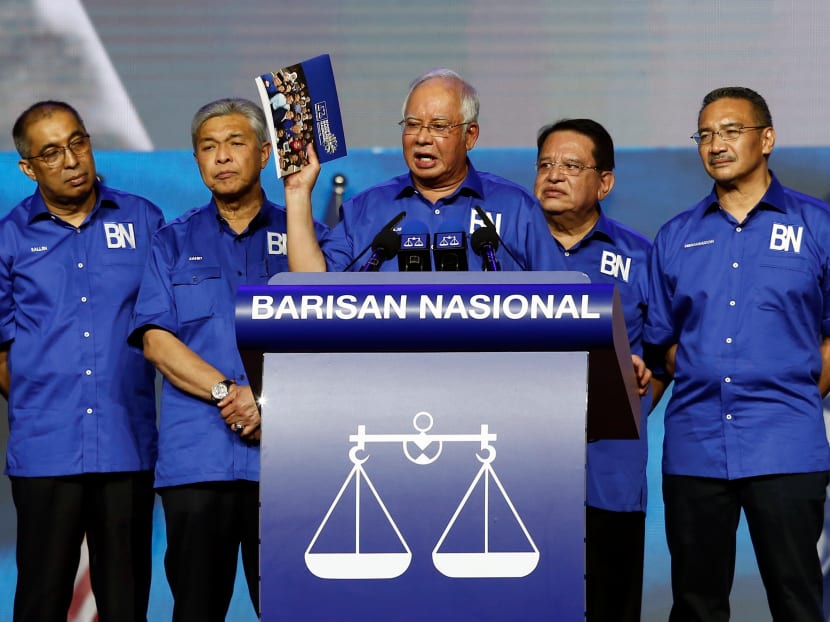

Prime Minister Najib Razak holds up a booklet on BN's manifesto during its launch on April 7 alongside other coalition leaders.

The one-upmanship of Malaysia’s electoral contest has heightened with Barisan Nasional’s (BN) manifesto launch on April 7.

At a rock concert-cum-jamboree like event at Bukit Jalil Axiata Arena, BN chief Najib Razak brandished the 220-page document, and trumpeted his administration’s achievements and pledges to a raucous blue sea of uniformly dressed supporters.

The stage and crowd made a key statement: BN’s unveiling was going to be bigger, louder and grander than the modest one by the Pakatan Harapan (PH) opposition pact a month earlier.

Then came the promises.

Datuk Seri Najib promised three million jobs, compared to PH’s one million (to be fair, PH made a more specific promise of one million jobs paying above RM2,500 (S$842) per month).

Datuk Seri Najib promised continuation of infrastructure spending and the extensive social assistance in place, and proclaimed targeted benefits for women, young adults, Felda communities, and Malaysia’s diverse states.

The manifesto climaxed with the promise of a windfall to the seven million low-income households and singles who receive BR1M, the cash transfer programme.

BR1M’s next two disbursements will be doubled, from RM400 to RM800, to be paid in June and August. PH had pledged to merely retain BR1M.

The slogan Bersama BN, Hebatkan Negaraku (With BN for a greater Malaysia) apparently deserved a thick book splashed with feel-good graphics.

While 220 pages long, it contains only 6,000 words; PH’s English-translated manifesto packs 28,000 words onto 149 pages of plain text.

Both style and substance speak volumes. The BN manifesto outdoes its predecessors in heft, gloss, and perhaps sweetness.

But it reverts to the habitual formula of reminding people of material gains delivered, persuading voters that only BN can do the job, raising the spectre of lost patronage should it not be voted back, and treading softly on matters of institutional reform.

However, the deep disquiet on the ground, greater access to information and increased expectations of government, pose challenges to BN’s repackage of old ways.

Time will tell if BN has overcooked its self-appraisal, overestimated the electorate’s fear of losing BN patronage and protection, and overplayed its attempt to pass off minor administrative tweaks as significant reforms and anti-corruption efforts.

In elections, incumbents magnify success and minimise shortfalls.

But in BN’s own eyes, it has not just done well – it has been near perfect. The BN has proudly proclaimed that it has fulfilled 99.4 per cent of promises made in the 2013 general election (GE13), to be precise.

It can legitimately claim to have fostered steady economic growth and delivered social programmes.

Many achievements can be factually proven: BR1M has been increasingly paid, the MRT built, public education and health funded.

Other claims of success are however questionable, and some are plain wrong.

On education, BN’s GE13 pledge was to bring Malaysia into the top third of the world, but it is still in the bottom half based on international standardised tests.

On housing, its promise back then was to build one million affordable units.

To date, 240,000 have been completed, 280,000 are being built and 590,000 are planned. To qualify this as a fulfilled promise stretches the imagination.

On corruption, BN promised in GE13 to empower investigative agencies, but it now turns evasive and derisory on this burning issue.

BN’s manifesto puts it in four peculiar spots, each posing tantalising questions.

First, ongoing clashes between statistics and sentiments persist. Can such a glowing macroeconomic report allay the discontent and anxiety of those who struggle to get by?

Will the populace credit a caring, capable government for coming to their aid with cash transfers and social assistance, or blame an out-of-touch, self-praising government for stagnant real incomes and socioeconomic hardships that make such support necessary?

Second, with PH presenting its own manifesto of welfare and populist policies, and PH-led state governments accumulating 10-year track records of social assistance and steady administration in Selangor and Penang, BN’s advantage has waned.

Will Malaysians feel indebted to their federal patron and believe that only BN can deliver, as they have in the past?

Third, any party scoring 99.4 per cent should be brimming with confidence, but BN’s efforts to engineer vote banks and disrupt voter turnout tell quite the opposite.

Just before dissolving parliament, Datuk Seri Najib led the Lower House to pass an Election Commission (EC) report on new constituency borders widely condemned as unconstitutional and unfair.

A few days after BN launched its manifesto, the EC announced that polling day will fall on Wednesday, May 9. Higher voter turnout corresponds with better results for the opposition.

Will these tactics work for BN, or might they even backfire?

Fourth, bread and butter issues take first place in voters’ minds, but this does not mean they care little for clean government and matters of conscience.

BN’s pledge to be more responsive will be welcomed, but its dismissive and cavalier attitude toward systemic corruption may not go down so well.

The manifesto promises to draft – not necessarily pass – legislation on political party financing.

In fact, the Najib administration formed a committee for such a purpose more than two years ago, but failed to bring anything to parliament.

One might expect that, on the heels of high profile scandals involving 1MDB, Felda, and MARA, BN would at least record some acknowledgement of the problem of corruption without mentioning names.

The manifesto treats big, federal-level corruption as nonexistent, or perhaps settled in the manner of 1MDB’s burial, and proposes solutions for government transparency only at the local level.

This is astounding, after BN made combating corruption a cornerstone of the 2004 elections that it won by a landslide, and pledged in its GE13 manifesto to “fight the scourge of corruption”.

For GE14, BN has done away with a dedicated section on corruption, and merely makes oblique proposals for secured online transactions as a means to reduce graft.

Will this be adequate for Malaysia’s voters, or have they become unyieldingly demanding on issues of governance and principle?

GE14 will provide some answers, but BN’s calculation thus far is clear.

Malaysia’s incumbent coalition is counting on a sizable minority of Malaysians – a majority is unnecessary, given the imbalances in the electoral system – being satisfied with material benefits and promises, and comfortable with its patronising ways.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Lee Hwok-Aun is a senior fellow at the Iseas-Yusof Ishak Institute.