Charisma matters. But can it be taught?

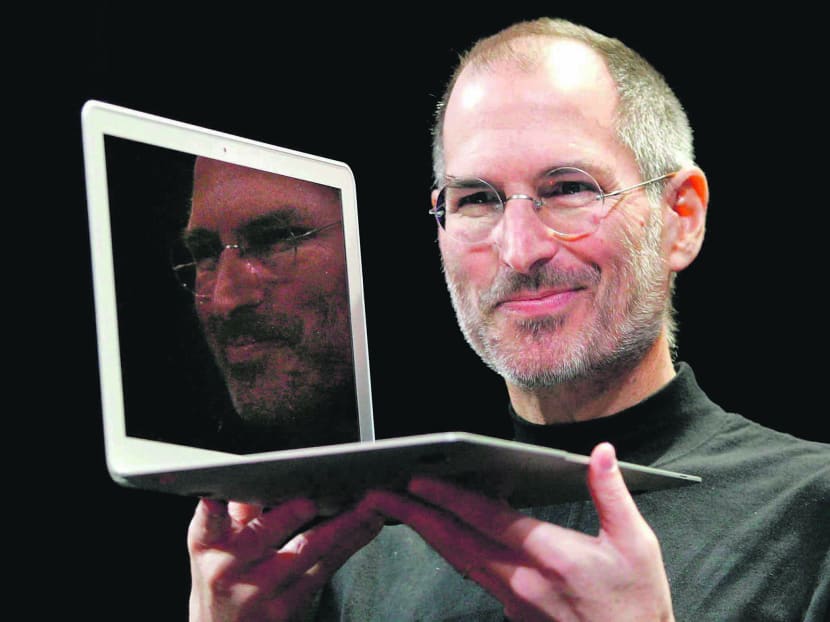

When Steve Jobs, the late chief executive of Apple, launched the Macintosh computer in 1984, he hid behind the lectern, reading from notes and glancing at his feet.

When Steve Jobs, the late chief executive of Apple, launched the Macintosh computer in 1984, he hid behind the lectern, reading from notes and glancing at his feet.

By 1996, he was walking around the stage, speaking fluently. But he was still stiff, much like the Tin Man character in The Wizard of Oz movie, says Ms Olivia Fox Cabane, who teaches charisma to chief executives. By 2000, when he announced his return as chief executive of Apple, Jobs had turned into a showman.

At that point, “he owns the stage. His eye contact is outstanding, hand gestures are carefully orchestrated and in fact, he’s using the same techniques as professional magicians”, she writes.

Ms Cabane, author of The Charisma Myth, is one of a growing band of experts making a living out of teaching senior executives that “personal magnetism” — a combination of presence, power and warmth — can be learned.

Her argument is supported by academic research, which shows that people taught charismatic skills are more likely to be followed.

Drawing from his team’s study, Dr John Antonakis, professor of organisational behaviour at the University of Lausanne, says that leaders who learn 12 charismatic traits — such as using an animated voice or expressing moral conviction — become more “influential, trustworthy and leaderlike”.

Charisma influences everyone from voters to company chairmen. Dr Antonakis says he and his team can predict who will win the United States presidency on the basis of which candidate has more charisma and how well the incumbent party has handled the economy.

They found similar results in an experimental study where the probability of a chief executive being reappointed depended on his or her charisma and the organisation’s performance.

LEARNING TO BE A LEADER

Although many of us assume charisma is something a person either does or does not possess, experts say we can all be taught the seemingly indefinable allure of Mr Bill Clinton or Mr David Beckham.

Mr Richard Reid, who runs charisma classes for companies including Google and Ernst & Young, says it is about finding a style that suits your personality.

The trick is to “celebrate each individual’s uniqueness” or it will seem artificial, says Mr Reid. He says Mr Ed Miliband, who lost the race to become Prime Minister of the UK this year, received coaching but “became increasingly inauthentic along with it”.

Much of the emphasis in Mr Reid’s training is on body, rather than verbal, language — especially “micro-manoeuvres” such as holding someone’s gaze. First impressions count, and even a seemingly involuntary blink of the eye can weaken your influence when meeting someone for the first time, he says, adding that it takes a lot longer to establish trust once an opportunity is lost.

To maximise your chance of getting it right, he suggests picturing a time when you felt most confident before entering a room to meet someone important or give a presentation.

People are drawn to those who are purposeful and can make them feel safe and heard. Mr Reid compares it to throwing “an arm around the shoulder” and whispering: “Can you see my vision with me?”

He suggests being an active listener. One way is to interrupt a conversation partner, saying you are doing so “to make sure I’ve understood”, and then to repeat the speaker’s words.

“Although we think we’re good listeners, we’re not,” Mr Reid says.

If you are trying to persuade someone they want to go to Madrid rather than Rome do not use the word “why”, for example. “Why” is often perceived as a challenge, so it is best avoided when undergoing a workplace performance evaluation.

In conflict, people tend to end up face to face, jabbing fingers at each other. Mr Reid advises angling your body and referring to the problem as if it is slightly beyond the both of you.

Although useful techniques, they beg the question of whether these are anything more than good communication skills.

Mr Rob Shimmin, an executive coach for multinationals including Dell, Visa, DuPont and De Beers, admits, “You can learn to be credible, but not necessarily charismatic.”

He believes many of the traits that breed charisma, much like the rest of personality, are set in childhood. “You can’t buy charisma, be it from a smart corporate coach or a private school.”

But you can get close.

“The better able you are to learn the behaviours of charismatic people, the more impact you are likely to have when you communicate.”

FINANCIAL TIMES

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Gill Plimmer is a journalist at the Financial Times.