Economics, not ecology, drives countries to act on climate change

It all feels a bit familiar as, five years after the Copenhagen debacle, world leaders gather in New York today to talk about reaching a global agreement on tackling climate change. The summit is expected to launch another long trek towards a treaty at the end of next year.

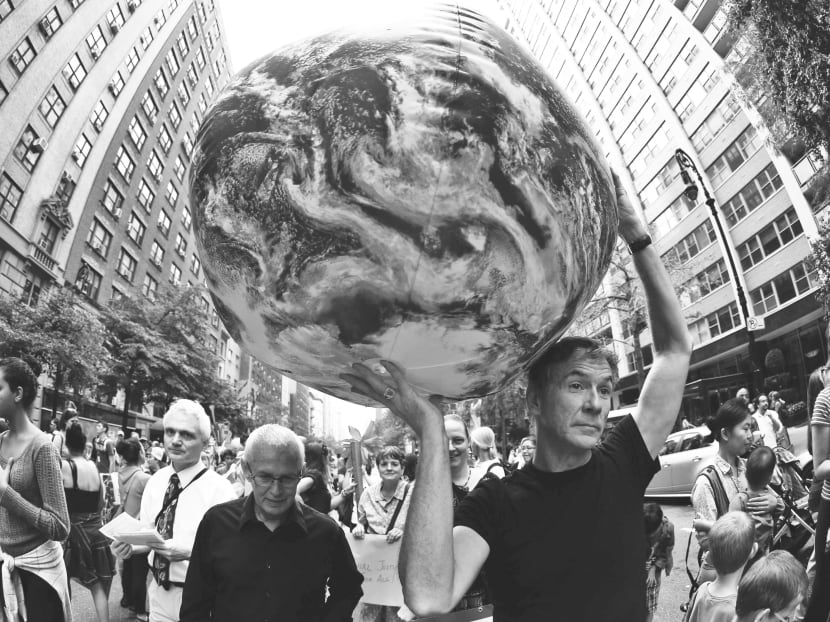

Hundreds of thousands joined the People’s Climate March in New York on Sunday, ahead of tomorrow’s UN Climate Summit in the city to discuss reducing carbon emissions. Photo: Reuters

It all feels a bit familiar as, five years after the Copenhagen debacle, world leaders gather in New York today to talk about reaching a global agreement on tackling climate change. The summit is expected to launch another long trek towards a treaty at the end of next year.

But this time almost everything is different from 2009, when the talks failed. Economics is figuring larger than ecology this year. Some of the most obstructive countries in Copenhagen are now pushing hardest for a treaty, while some of the keenest back then look like they are dragging now. And — though environmentalists do not like admitting it — the world is making progress through adopting a suggestion from the much-reviled Mr George W Bush.

There are, of course, some things that stay much the same. Global emissions of greenhouse gases continue unabated: This month, the World Meteorological Organisation reported that they grew at their fastest in three decades last year, and are now at record levels. And Christiana Figueres, United Nations chief of the treaty negotiations, warned again that time to curb them is running out.

Nevertheless, the buzz is more about expanding economic opportunities than impending ecological disaster, real though that may be.

The key report published last week in preparation for the summit was not from Greenpeace, Friends of the Earth or any of the usual suspects, but rather by leaders of the International Monetary Fund, Bank of England, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, China Development Bank, World Bank and businesses usually treated as enemies by greenies.

Its message?

Tackling climate change can help, not harm, economic growth.

Hard cash increasingly says so too. Last year, there was greater worldwide investment in renewable energy than in fossil fuels for the fourth year in a row, as the cost of solar and windpower tumbles. The worldwide market in low-carbon goods and services exceeds £3.4 trillion (S$7 trillion) a year and often outperforms the rest of the global economy.

No country has seen the opportunity more clearly than China, now the world’s biggest renewables investor. Formerly better known for rapidly building coal-fired stations, it has closed and cancelled scores of them, mainly to combat the air pollution that kills some 250,000 Chinese a year.

China, the main obstacle to progress in Copenhagen, is now taking the lead in calling for action — along with that other erstwhile bugbear, the United States. United States President Barack Obama and his Secretary of State John Kerry have made securing a climate treaty a legacy issue. The President, by taking executive action to get round an obstructive Congress, and aided by the rapid expansion of shale gas, is bringing down US emissions.

India’s recent elections — says Britain’s Energy Secretary Ed Davey — have “changed the mood” in another traditionally reluctant nation. Mr Narendra Modi, the new Prime Minister, boosted renewables while serving as Chief Minister of Gujarat, and Mr Davey says he “has the will and commitment” to do the same nationally.

CAN CAPITALISM CLEAN UP THE WORLD?

By contrast, the European Union — which led the push for change in Copenhagen — has been growing less enthusiastic and the new president of the European Commission, Mr Jean-Claude Juncker, seems determined to downgrade the issue.

The emerging agreement, too, is totally different from the one on the Copenhagen table. That sought to set a global ceiling on greenhouse gas emissions and then divide them between nations. This one starts at the other end, with governments pledging what they think they can achieve — a concept originally advanced by former US President Bush.

For the first time, all nations, including the smallest and least polluting, will join in. But the scheme has an obvious flaw. It is most unlikely that the pledges will be nearly enough to head off serious climate change; PricewaterhouseCoopers has calculated that international efforts would have to increase fivefold to do so.

But it is the best that is reasonably achievable. And the, not unrealistic, hope is that — once a clear signal is given that the future is low carbon — the competitive power of capitalism will rapidly cause the world to exceed the targets.

Yet, disappointingly, Mr Modi, China’s President Xi Jinping and German chancellor Angela Merkel will not be at the New York summit. Inevitably, their absence diminishes it — but, equally, it opens up an opportunity for David Cameron.

Every British Prime Minister for the past 35 years has played a central, constructive and often crucial role in climate negotiations. Mr Cameron, more than any since Margaret Thatcher, firmly believes in their importance.

He has, of course, been pretty quiet on the issue of late. But, as the Scotland referendum for independence has shown, critical times call for the courage of prime ministerial convictions. THE DAILY TELEGRAPH

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Geoffrey Lean is Britain’s longest-serving environmental correspondent, having pioneered reporting on the subject almost 40 years ago.