Facing up to identity, myths and politics in S’pore

Throughout the Singapore Conversations, and especially in the furore over the Population White Paper, the question of the Singaporean identity has taken centre stage.

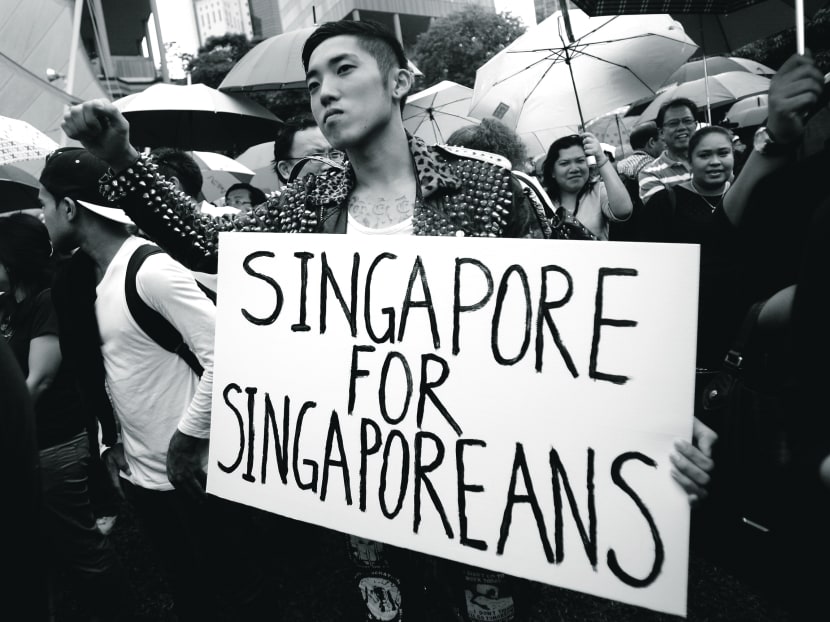

Will identity-making be driven by fear, distrust and pessimism — or by openness, fairness and an embrace of difference? Photo: Reuters

Throughout the Singapore Conversations, and especially in the furore over the Population White Paper, the question of the Singaporean identity has taken centre stage.

Whether the focus has been on the day-to-day issues of jobs, the cost of living, transport, housing and the like, or on the longer-term ephemeral visions of a shared future, of grave concern has been the erosion of the Singaporean identity by the influx of immigrants brought on by deteriorating demographic trends. The fear is that this sense of “we” will disintegrate, or at least alter irretrievably, in the face of “they”.

Of course, it is right to be concerned about the cohesiveness of national identity, and how it might change over time.

It is worth remembering, though, that once upon several times, the different incarnations of “we” can be traced to distinct cohorts of “they” sailing or flying to these shores.

Still, dangers exist, though not in the crude terms of the unravelling of the Singaporean identity; rather, they lie more subtly in how we define Singaporean-ness.

THE MYTH OF ‘US’

Stating that a collective identity matters is obvious to the point of being banally so.

Identification with something bigger than the individual — tribe, village, guild, religion, ethnicity, nation — locates a person in space and time, and supplies the essential meaning that transforms mere existence into living.

In the face of globalisation, identity anchors the individual amidst barely-understood, traumatising changes. Indeed, the sociologist Manuel Castells notes that as the world gets more global, people feel more local. The angst that has gripped Singapore as it grapples with globalisation, immigration and identity certainly testifies to that.

The most basic form of identification that people make is with their locality.

This territorial identity is, in turn, built on the various myths that people tell about themselves and the place they live. It is the charter myths of a society that imbue a place with meaning.

For Singapore, the charter myths are known to all: The heroics of August 1965, resilience in overcoming vulnerabilities, ingenuity in transcending limitations, the kampung spirit, and so on. These myths form the basis of our collective identity, legitimising ourselves as a distinct people.

Bear in mind that we are talking about myths, not historical facts. Take kampung spirit, for example. Did it really exist once upon a time in Singapore, whenever that time was? Maybe it did for some, and not for others.

It actually doesn’t matter; what does matter is how people now act, believe and reminisce as if it once did. Indeed, the power of a society’s myths rests not so much on how “real” they are, but on how they inform the social consciousness and are transmitted down the generations.

Even an imagined past constitutes a reality of its own, and has the power to inspire, mobilise, and galvanise a collective identity.

THE WAY WE THINK WE ARE

In a sense, the current debates about Singaporean-ness are an exercise in self-consolation: People re-imagining their founding myths as a rearguard action fought in repelling the ever-encroaching Others.

There seems to be a wistful longing for how things used to be, or at least how they were imagined to be before the Others came along.

When collective identity is re-articulated in a manner that excludes, and even vilifies, newcomers, then a vicious chain reaction is set in motion: The excluded retaliate by excluding the excluders, creating more schisms.

If identity is not a once-and-for-all constructed artefact, but a work-in-progress that is continually re-negotiated, then it is the process of identity-making that matters more than identity itself.

With a growing nostalgia for a re-imagined past driven by frustrations with the present and fears for the future, the business of governing “the people” becomes more problematic if simply because defining “the people” becomes the first order of business.

Which Singaporean identity will emerge — an inclusivist or exclusivist one?

It will depend on which myths prevail: The myth of a better bygone age that people cling to in the face of the intruding Other, or the myth of our own immigrant past that grounds and assures us as we become more and more a global city?

Will identity-making be driven by fear, distrust and pessimism — or by openness, fairness and an embrace of difference?

Increasingly, the Government must address the abstract and elusive issues of who we are, what we stand for, and where we are headed.

The primordial anger at losing one’s identity is such that it negates the rationale for immigration policy, however sound. As such, policymakers must now concern themselves with the myths and ethos that are the very basis of our identity.

The name of the game isn’t simply about policymaking anymore; it is politics.

Dr Adrian W J Kuah is an Assistant Professor at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University.