Heeding the lessons from 50 years of Indonesia-S’pore ties

Indonesian President Joko Widodo is scheduled to meet Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong at a leaders’ retreat in Singapore on Sept 7, in conjunction with the 50th anniversary of bilateral ties.

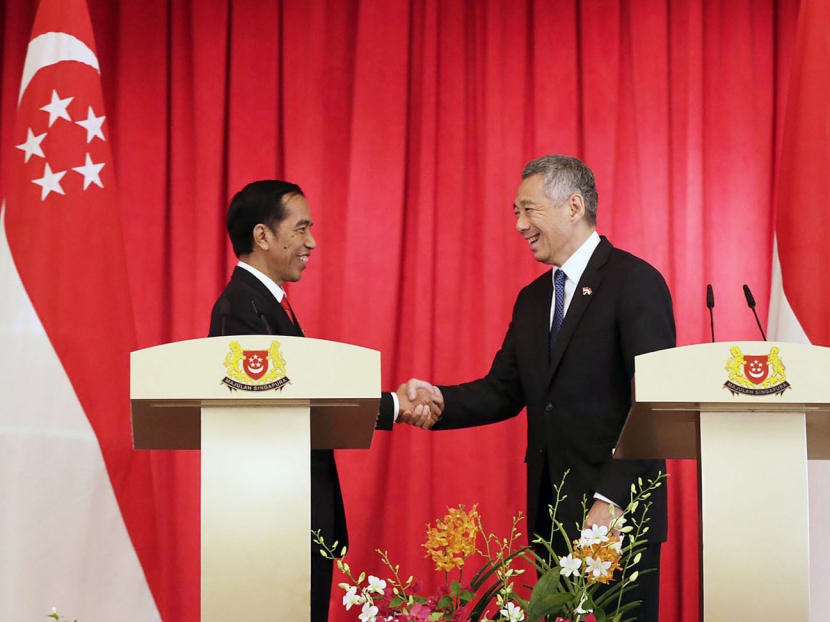

President Joko Widodo and Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong at the Istana in 2015. Despite episodes of tensions, the nations have maintained harmonious ties over the past 50 years. TODAY file photo

Indonesian President Joko Widodo is scheduled to meet Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong at a leaders’ retreat in Singapore on Sept 7, in conjunction with the 50th anniversary of bilateral ties.

Indonesia-Singapore relations, after initial uncertainties and suspicions, have matured in the past 50 years. What lessons can be derived for relations for the next five decades?

The establishment of diplomatic relations in 1967, signified by the official opening of the Singapore Embassy in Jakarta, was marred by suspicions and tensions arising from the aftermath of Konfrontasi.

The uneasy beginning is exemplified by the trial and hanging of two Indonesian marines in October 1968 convicted for the bombing of MacDonald House in 1965, which led to the ransacking of the Singapore Embassy in Jakarta. Tension remained until then-Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew’s visit to Indonesia in 1973, during which he scattered flowers over the graves of the marines, bringing a symbolic closure to the Konfrontasi chapter.

Post-Confrontation, Indonesia-Singapore relations flourished. Indonesia and Singapore’s participation, together with Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand, in the founding of the Association of South-east Asian Nations (Asean) in 1967 marked the departure from the turbulent relations.

More significantly, PM Lee Kuan Yew and President Suharto established a personal rapport that underpinned the close and friendly relations that bloomed over the next three decades, despite occasional tensions over security issues.

Among them was Indonesia’s occupation of East Timor in 1975, over which Singapore abstained from the United Nations resolution that condemned Indonesia’s occupation, while other Asean member states voted against.

Notwithstanding the occasional strain in relations, Indonesia and Singapore developed robust cooperation in defence and security matters, and conducted joint military training exercises, thus enhancing mutual confidence and trust.

Both countries had a mutual interest in seeking to forge “regional resilience” through their respective national resilience, to withstand the various challenges arising from global geopolitics. Bilateral economic cooperation expanded, particularly in trade and investments, as Indonesia’s economy developed and invited Singapore to invest in industrial parks in Riau Islands and Sumatra.

The abrupt collapse of the New Order and the downfall of Mr Suharto against the backdrop of the 1998 Asian financial crisis ushered the dawn of Reformasi, another challenging chapter in Indonesia-Singapore ties.

The changed political landscape with the emergence of pro-democracy forces meant that Singapore could no longer rely on the rapport between Mr Suharto and Mr Lee Kuan Yew, nor the networks forged under the New Order government. Thus Singapore had to forge new linkages with emerging Indonesian elites to maintain mutual understanding and rebuild partnerships.

The rise of regional and local leaders accompanying decentralisation in post-Suharto Indonesia generated new political dynamics that Singapore had to contend with. Nevertheless, Indonesia-Singapore ties remained robust, exemplified by the many sectors in which the countries have cooperated, from trade, communications, tourism, community and cultural exchanges to defence and security, as well as Asean integration.

The positive development of post-Suharto bilateral ties is best illustrated on the economic front. Bilateral trade in 2015 amounted to US$58.7 billion (S$79.8 billion), compared with US$10.4 billion in 2000, making Indonesia Singapore’s fourth-largest trading partner in that period.

Singapore has consistently been Indonesia’s gateway for foreign direct investment (FDI) in recent years. Official Indonesian figures show FDI into Indonesia from Singapore last year totalled US$9.1 billion, with more than 5,800 projects, whereas investment from Japan and China amounted to US$5.4 billion and US$ 2.6 billion, respectively. Both countries recently launched an industrial park in Semarang (Central Java), a joint development inaugurated by President Widodo and PM Lee Hsien Loong.

Defence and security ties have remained strong, as exemplified by regular joint military exercises, the trilateral coordinated maritime patrols in the Malacca Strait to counter piracy, and security cooperation against transnational terrorism.

Singapore was also involved in humanitarian assistance and disaster relief in Indonesia, namely in the tsunami-hit Aceh in 2004, Yogyakarta in 2006, and in search-and-rescue efforts for the ill-fated AirAsia QZ 8501 in 2014.

Above all, the Indonesian and Singaporean leadership remain committed to cordial ties.

UNDERCURRENTS

AND CHALLENGES

Certain undercurrents persist in Indonesia-Singapore relations, such as the trans-boundary haze from Indonesia, issues surrounding the status of Indonesian assets parked in Singapore, and demand by certain Indonesian quarters for control of the airspace over the Riau and Natuna Islands. These aside, the formative history of Indonesia-Singapore relations, such as Konfrontasi and the PRRI/Permesta rebellion in the late 1950s, when foreign economic and military assistance was funnelled through British Singapore, have shaped Indonesia’s perception of Singapore. This might re-emerge and incite tensions.

The brouhaha in 2014 surrounding the naming of the ship Usman Harun (after the two hanged commandos) is a testament to how residual grievances persist. There may be other unexpected undercurrents that could affect relations. An example is the recent limitation on Singapore Airlines flights to Indonesia due to runway improvements at Jakarta’s international airport.

Domestic elements within both countries and deeply entrenched negative perceptions of each other may further impinge on bilateral relations.

Both countries also face common challenges from the regional strategic environment and the growing assertiveness of extra-regional powers. China’s claim over most of the South China Sea, for example, potentially affects the freedom of navigation and overflights of the international waterway that both countries rely on.

Moreover, the ensuing great power rivalry in the Asia-Pacific has driven a wedge in Asean and undermined its hard-earned cohesion.

That said, China’s 21st Century Maritime Silk Road initiative offers an avenue for both countries to pursue new economic opportunities. Singapore has a common interest in Indonesia’s vision to play its role as a “Maritime Fulcrum” along the revived Maritime Silk Road connecting the Western Pacific with the Indian Ocean.

The past 50 years of Indonesia-Singapore relations have shown that despite the episodic instances of discord and tensions, the countries have a strong interest in maintaining harmonious bilateral relations for their mutual benefit.

Despite the close and warm ties overall, discord could still flare up to mar relations in the future given the persistence of undercurrents in ties, domestic perceptions of each other and new dynamics in their common strategic environment.

Nevertheless, going forward, both Indonesia and Singapore should not let discord and tension define their relations. On the contrary, both countries need to maintain their close cooperation as good neighbours and good partners in Asean. They need to build new initiatives while cultivating existing channels of communication to enhance mutual understanding.

How relations develop in the next 50 years will be determined chiefly by the domestic politics of both countries; the changes in the South-east Asian region; as well as the progress of the Asean Economic Community, which will involve their economic relations with the rest of Asean.

Notwithstanding their contrasting sizes, populations, resources and economies, Indonesia and Singapore share a common geopolitical destiny and a shared geostrategic future; they are both at the crossroads of the Indo-Pacific region astride the fulcrum of South-east Asia.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Keoni Marzuki is a Senior Analyst at the Indonesia Programme, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University. This was adapted from a piece which first appeared in RSIS Commentary.