Holding on to home in war and peace

My father likes to tell the story of how, when he was five, his father was hit by a Japanese aerial bomb only days before the country occupied Singapore in 1942. For weeks, our relatives searched for Grandpa in the hospitals and morgues. Surrounded by cooing neighbours, Grandma wailed the whole time, thinking he was dead.

My father likes to tell the story of how, when he was five, his father was hit by a Japanese aerial bomb only days before the country occupied Singapore in 1942. For weeks, our relatives searched for Grandpa in the hospitals and morgues. Surrounded by cooing neighbours, Grandma wailed the whole time, thinking he was dead.

One day he woke up in a hospital bed with a face wrapped in bandages and sent word that he was alive. Suddenly everyone could breathe again. Grandpa lost many teeth, was scarred in the jaw and, for years after, would find bits of shrapnel stuck to plasters that he peeled off — but at least he was back.

More than 70 years later, stories of the war in Singapore are becoming a distant memory. My generation is lucky to have known only peace. But conflict and family separation are still daily realities in many parts of the world.

Yesterday was World Refugee Day, a day to pay tribute to the courage and resilience of people forced to flee their homes because of war and persecution.

According to figures just released by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), more than 45.2 million people were in situations of displacement by the end of last year. This includes 15.4 million refugees, 937,000 asylum-seekers and 28.8 million people forced to flee within the borders of their own countries.

Fifty-five per cent of all refugees come from Afghanistan, Somalia, Iraq, Syria and Sudan. Forty-six per cent of refugees are children below 18 years of age. As if that wasn’t bad enough, every 4.1 seconds, someone new is displaced from his or her home.

SHELTER IS NOT ENOUGH

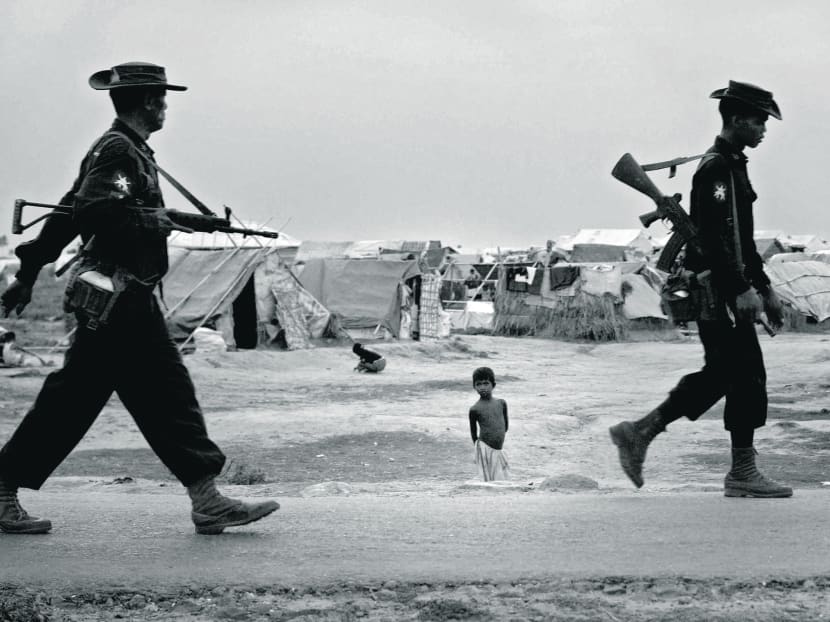

Conflict and displacement are not someone else’s problem. In South-east Asia, inter-communal violence has uprooted as many as 140,000 people in Myanmar’s Rakhine state. As homes burnt last June and October, families fled with only the clothes on their backs. Many sought refuge in local villages, in tents and makeshift shelters.

A year after the initial riots, many displaced people are now living in temporary bamboo shelters built by the Myanmar government, UNHCR and other aid agencies. But it is not enough to have a roof over the head and food in the stomach.

When I visited recently, parents were worried about basic livelihoods and the fact that their children have missed a year of school. No one knew when they could go home to rebuild from the ashes.

The unrest in Rakhine state has affected not only local families but also the families of aid workers. In the UNHCR, our shelter coordinator has not seen his wife and children in months. He spends his days doing site planning and building temporary shelters for displaced people. For a long time, his children had no idea what Daddy did, except that he was gone a lot and always returned sunburnt and exhausted.

Another colleague’s husband and children have uprooted themselves to join her in the field. Despite her demanding workload, they try really hard to have a normal family life in this unusual setting.

ONE FAMILY TOO MANY

One family torn apart by war is too many, states the slogan for this year’s World Refugee Day campaign.

It seeks to show the impact of war on families and the difficult choices they have to make to flee and survive. When families are forced to escape the violence, they may have only a minute to gather what they need.

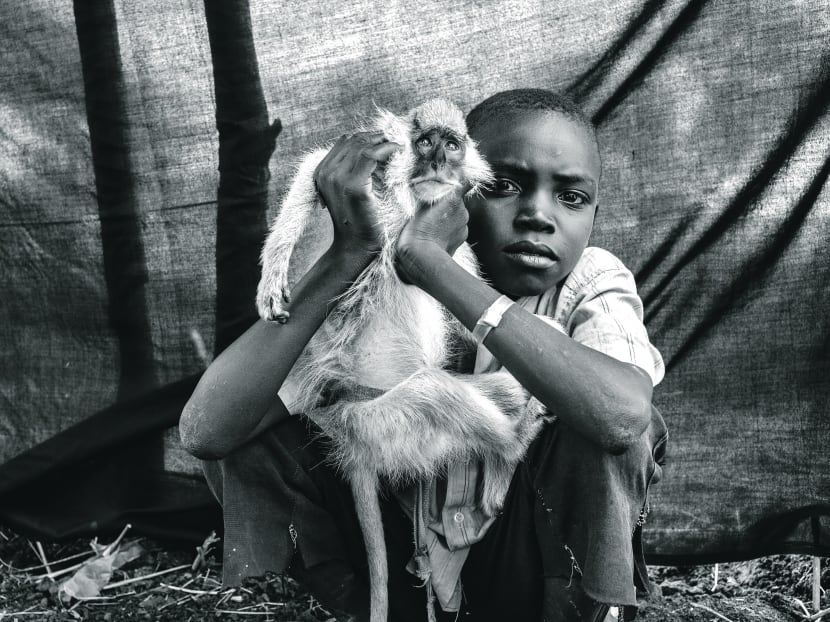

American photojournalist Brian Sokol has captured this split-second decision in a stark and heartbreaking photo series called The Most Important Thing. He asked refugees from Sudan and Syria to show him the most prized possession they brought into exile. The treasures are surprising — pots, pets, photos, keys, jewellery, musical instruments and a wheelchair.

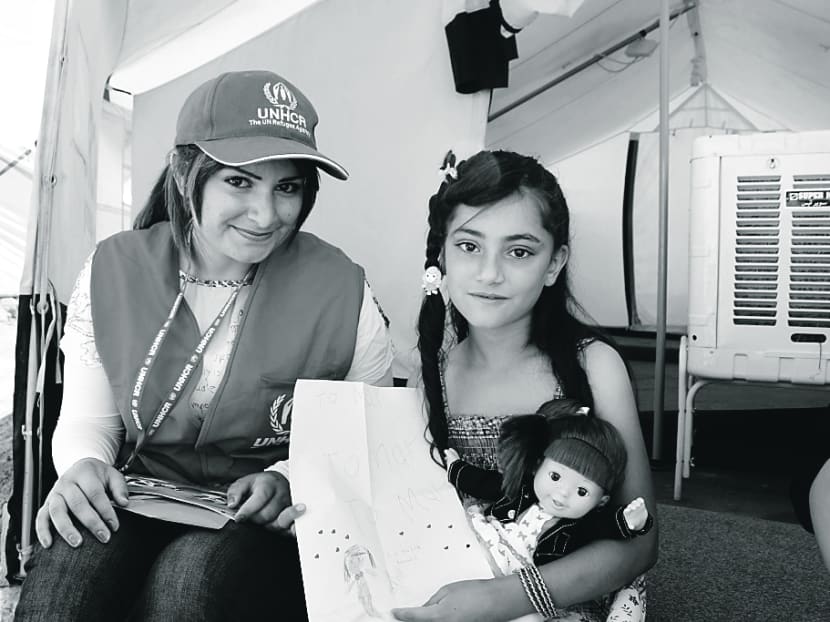

May, an eight-year-old Syrian refugee in Iraq’s Domiz camp, modelled the bangles she managed to salvage before fleeing but mourned the prized doll she left behind. Thousands of kilometres away in Bangkok, a five-year-old British girl named Mimi saw the photo online and decided to dig into her piggy bank to buy a doll for May.

The first obstacle was choosing the right doll. At the store, Mimi’s mother almost had a heart attack at the thought of sending a scantily-clad Barbie to the Middle East. Eventually they found a culturally appropriate one. Obstacle Two was getting the doll to May. They contacted the UNHCR and we managed to deliver it by hand, from Bangkok to Geneva to Jordan to Iraq.

When May finally received the doll last week, she was surprised and delighted. She has named the doll Mimi after her benefactor and hopes that one day they can play together. The girls are living proof that, with a little help, small acts of kindness can make a big difference.

Around the world, UNHCR staff have worked tirelessly to assist, protect and seek solutions for the world’s forcibly displaced people since 1950. The organisation has been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize twice in recognition of these efforts.

World Refugee Day is marked on June 20 each year. To find out how you can help refugees like May, go to the UNHCR website http://unhcr.org/1family

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Vivian Tan is a Singaporean working for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees as the Senior Regional Communications Officer based in Bangkok.