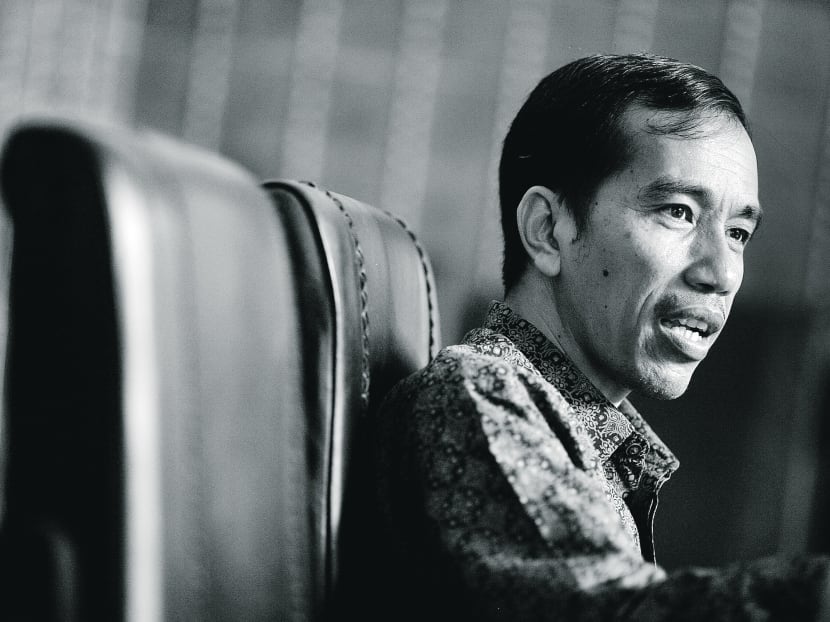

Jokowi’s lesson in meet-the-people politics

All politics is local. But hot-button issues differ from country to country and city to city.

All politics is local. But hot-button issues differ from country to country and city to city.

In Kuala Lumpur (after a spate of shootings, many fatal), it is crime and affordable housing. In Singapore, it is affordable housing and transport. In Jakarta and Manila, it is traffic congestion and flooding.

Everywhere, though, South-east Asian leaders are fast discovering that urban voters can be a nightmare to handle: They are distrustful of authority, quick to criticise and ungrateful.

Social media adds to the complexity of managing these cities; the flow of information now hurtles out of anyone’s “control”.

Local politicians need to be humble and consultative. Sadly, there are representatives across South-east Asia who think an election victory is a licence to print money.

What they have failed to comprehend is that we now live in an era where urban voters no longer kiss the hands of their elected representatives.

Given these challenges, how do you govern these communities? Look to Indonesia.

Specifically in Jakarta — Southeast Asia’s largest conurbation — a seemingly minor market relocation has mushroomed into a critical challenge for its Governor, Mr Joko Widodo (or Jokowi).

While many are talking about his potential as a presidential candidate, the really interesting thing about him is his unexpected leadership style. In fact, it does not matter whether he stands in the coming 2014 elections because he has already shaken up the Republic’s politics, forever.

THE TANAH ABANG CHALLENGE

The capital’s Tanah Abang market (a popular destination for Malaysian shoppers) is a vast commercial hub whose tentacles reach deep into virtually every hamlet of the 240 million-strong nation.

Famed for its textiles, the market has been in existence for well over 250 years. With an estimated 28,000 merchants plying their wares and spread over six floors — including a 2,000-person capacity mosque — Tanah Abang is one of Asia’s busiest trading centres.

And with Lebaran (Hari Raya) approaching, Tanah Abang with all its traders mutates into a Bermuda Triangle of sorts — snarling traffic for miles all around, including the all-important Jalan KH Mas Mansyur, one of the capital’s main north-south arteries (bankers use the road to reach Bank Indonesia).

The 700-odd street vendors outside the main structure are the main source of the congestion. But persuading them to relocate requires tact and perseverance.

Besides the vendors, there is an entire infrastructure of vested interests from the local gangs (known as preman) to various businesses and the authorities themselves.

CONSENSUS BY LUNCH MEETINGS

Enter Jokowi, who faced a similar challenge during his earlier tenure as Mayor of Solo, Central Java.

Back in December 2005, he had convinced a group of street vendors in Solo’s Banjarsari Park to relocate to a new market in Kithilan Semanggi.

Jokowi was able to do this — as Ms Rushda Majeed wrote in a July 2012 case study for Princeton University’s Innovations for Successful Societies programme — by holding more than 50 lunch meetings with the vendors.

The meetings were not one-sided. He listened as much as he talked, pondering over their demands and collecting data as he worked towards a consensus.

This degree of inclusiveness is exhausting and not for the faint-hearted. However, the interventionist style has formed the basis for his leadership of Jakarta.

In order to resolve the knotty issue of Tanah Abang, he once again hit the ground to listen to the people.

The going has not been easy — Mr Jokowi and his deputy Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (Ahok) have been criticised by everyone from local politicians and national leaders to NGOs which have accused them of not understanding the needs of the street vendors.

However, patience appears to be paying off. Tanah Abang’s street vendors have finally agreed to move to a nearby alternative location, called Block G, where some 1,000 kiosks have been set up — rents will only be charged after six months.

ENGAGING THE GROUND

Jokowi’s ability to resolve the near-impossible may seem inconsequential, but this is actually a major transformational step for Indonesia. It proves that change — even in highly-politicised Indonesia — is possible, unlocking huge potential gains in infrastructural development.

Nonetheless, the key lesson is that change only happens when leaders engage with the people. In this respect the process — meetings, forums and discussions — are a critical part of the journey.

Jokowi’s blusukan (the Indonesian term for his meet-the-people encounters) is the vital ingredient in all this. By constantly hitting the ground and conducting sudden checks on his own civil servants, he won the trust of Jakartans.

And this trust is like social capital. Moreover, in communities where politicians are viewed with scepticism if not disdain, it means that people are more inclined to believe Jokowi. He is now drawing on this social capital in order to push through other programmes that benefit Jakartans, tackling flooding and traffic congestion.

For instance, he has also persuaded squatters in Pluit, North Jakarta, to move, freeing up space to boost the city’s flood prevention programmes. This, too, was a Herculean effort, involving the relocation of some 7,000 families — and the Governor was able to win their consent with a combination of gentle persuasion, humility and determination.

Blusukan (which Jokowi undertakes without scores of political aides and security officials) also ensures leaders stay in touch with the problems on the ground and truly understand what is going on.

In this sense, Jokowi is like former Singapore Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, with his emphasis on engagement and direct, first-hand knowledge. Both men share a passion for detail and delivery.

As South-east Asian anxieties about law and order as well as the rising cost of living continue to mount, our leaders could do well to visit Jakarta and observe the Governor in action. And they should practise blusukan — really listen and learn.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Karim Raslan is a columnist who divides his time between Indonesia and Malaysia.