Myanmar’s democratic transition in limbo

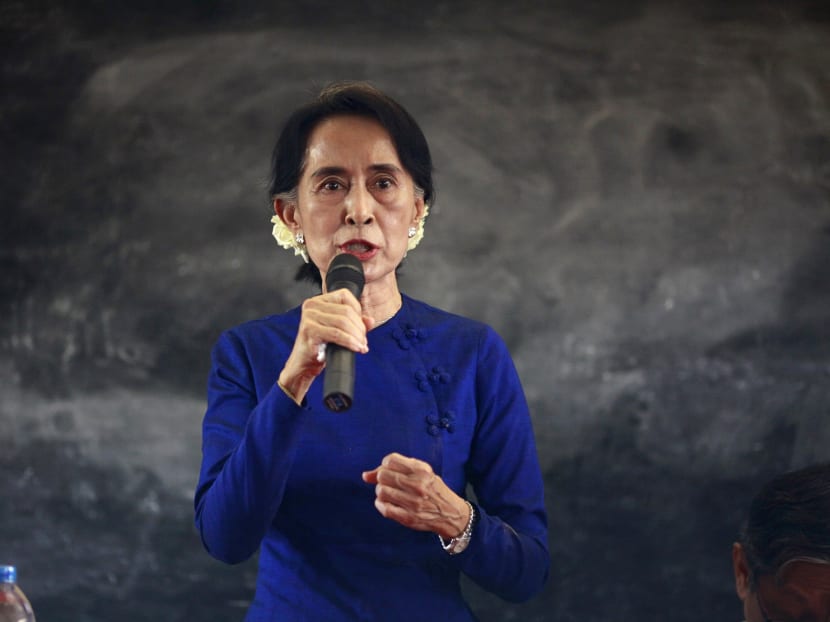

After 25 years of campaigning for free elections in Myanmar, Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy has at long last been able to hold some elections of its own. Last weekend almost 1,000 NLD delegates mustered in Yangon to elect a central committee.

After 25 years of campaigning for free elections in Myanmar, Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy has at long last been able to hold some elections of its own. Last weekend almost 1,000 NLD delegates mustered in Yangon to elect a central committee.

The irony was that not all members of the party were thrilled with the idea. After years of operating clandestinely under repressive military rule, the party is struggling to make the transition to a modern political organisation capable of taking the reins of power.

Older members, some of whom spent years being tortured in the country’s grisly jails, resent the fact that younger upstarts are moving in.

Ructions and jealousies are inevitable as the former opposition adjusts to the changes that have swept the country since the junta gave way to a form of controlled democracy in 2010. In many ways, Myanmar - which has held free by-elections, taken an axe to censorship and re-established diplomatic ties with the west - has come far further than almost anyone predicted even two years ago.

Many western businesses are now salivating at the prospect of the next Asian frontier, though most have, probably wisely, held off making big bets until the lie of the land becomes clearer. That will partly depend on how things like the much-haggled-over foreign investment law works in practice. Crucially, it will also hang on what happens politically.

ETHNIC FRAGILITY

Timothy Garton Ash, a British historian who has studied societies in transition, worries that Myanmar’s process could stall. Not for Ms Suu Kyi, he says, is the three-month whirlwind that swept Václav Havel from “persecuted dissident to the president’s castle” in Czechoslovakia.

General elections that could conceivably make Ms Suu Kyi president will not take place until 2015. By then, she will be 70. True, that gives her party, which has no experience of running a tea shop let alone a country, time to prepare for office. On the other hand, it puts the transition in a kind of limbo.

Perhaps the greatest danger would be if no political settlement were found before 2015 to ethnic conflicts that have rumbled on since independence in 1948.

At least 30 per cent of Myanmar’s estimated 55 million to 60 million people (no proper census has been taken in decades) are from ethnic minorities other than the majority Burmans. If minorities are not satisfied that they are fairly represented within a federal union, their politicians may be tempted to campaign for outright independence.

At best, that could cloud the elections. At worst, it could precipitate a Yugoslav-style break-up of a fragile country whose borders were never properly consolidated when it was part of British India.

What progress has been made in resolving ethnic tensions only goes skin-deep. The military-turned-civilian government has signed ceasefire agreements with several ethnic minority groups. But these are not expected to last if a political solution is not reached that awards ethnic regions a degree of genuine autonomy.

In recent days, a tentative ceasefire has been agreed with the Kachin, with whom fighting reignited in 2011. But the army has been accused of its old brutalities, including rape.

A DIFFICULT SPOT

All this has put Ms Suu Kyi in a tight spot as she makes her own transition from opposition deity to president-in-waiting.

She has dismayed some by not speaking out more strongly for persecuted minorities in Kachin and Rakhine state. She has also stressed her “fondness” for the army, words hardly likely to reassure ethnic minorities.

If she is ever to become president, she will need the military’s blessing. The current constitution bars her from holding the presidency on the grounds of her marriage to a foreigner, the late Michael Aris. That constitution can only be overturned by a 75 per cent majority in a parliament dominated by recently retired military or those still serving.

In other ways, too, Ms Suu Kyi is having to adjust to a new role. She was, doubtless to her discomfort, put in charge of a commission to investigate police brutality against monks who were occupying a Chinese-owned copper mine.

The inquiry’s conclusion was pragmatism itself: The police must learn better crowd-control methods, but the mine can continue operations and the contract with its Chinese owners should not be broken.

In public, Ms Suu Kyi is reasonably upbeat. But in private she is more critical of a government that, for all the political progress, has done little to improve the lives of ordinary people. The country’s poor may be worse off because of inflation. In the countryside, illegal land confiscations have intensified.

These are the practical problems that await a putative government led by Ms Suu Kyi. Some worry, not without reason, that the party lacks policy making depth and that its leader is surrounded by a group of yes-men, whose deference prohibits them from questioning her authority or judgment.

That is not ideal preparation for running a fragile democracy with huge social issues and geostrategic concerns. It’s a shame she has to wait so long to get on with it.

THE FINANCIAL TIMES LIMITED

David Pilling is the FT’s Asia editor.