Peer learning in the age of technology

When I was in high school, I studied sometimes with friends. If there was something I could not understand, it was easier to ask one of my friends who could usually explain it in a more understandable way than a teacher. And there was less pressure among peers.

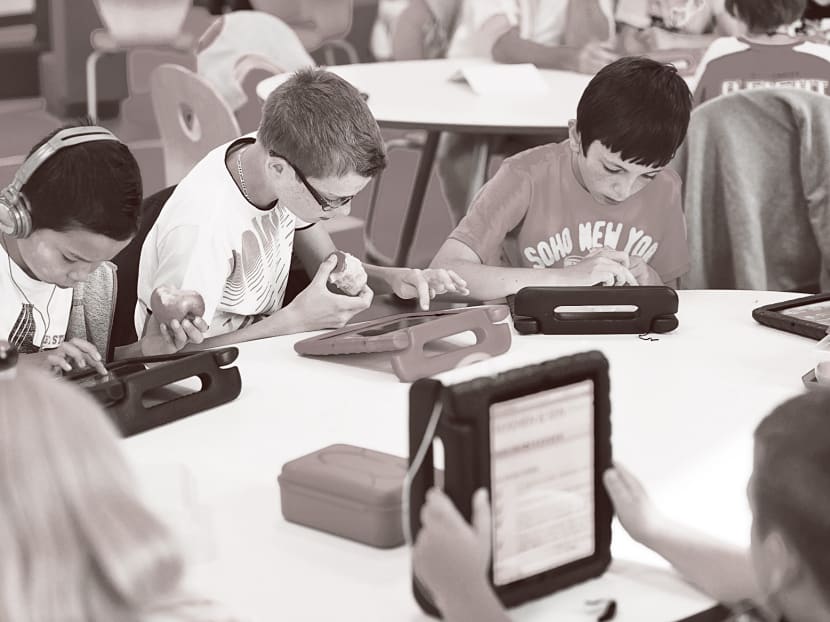

People learn all the time through engagement with peers as well as through their

links to the cyber world. PHOTO: REUTERS

When I was in high school, I studied sometimes with friends. If there was something I could not understand, it was easier to ask one of my friends who could usually explain it in a more understandable way than a teacher. And there was less pressure among peers.

Sometimes, a friend would pose a question to me. Trying to explain a problem helped me to see it with greater clarity and even with a new perspective. Dialogue and debate helped. Yes we competed, but we also helped one another out. We all had our strengths and weaknesses, but when tasked to work together, we did.

Examinations were key to moving ahead to the next step in our academic progression. We got together quite often to work on maths or science problems and sometimes compared and shared notes as a way to help one another learn. Today, watching my children and others, I see the same pattern, except that they do not meet in person — they chat using any number of social media tools, such as Facebook, Google Hangouts and WhatsApp. This form of collaborative learning has moved from face-to-face to the online world.

Peer and collaborative learning is as powerful today as it ever was, maybe even more so.

The Bobo Doll study is illustrative of how we learn. The Bobo Doll is a bottom-heavy inflatable toy, so when you knock it, it jumps back up.

Fifty years ago, social psychologist Albert Bandura conducted a simple experiment with young children.

Some children were exposed to aggressive behaviour towards the Bobo Doll, while others played quietly.

The children who witnessed the aggressive behaviour picked up the toy and showed the same aggression, unlike those who did not witnesssuch behaviour.

This shows that children pick up imitative behaviour even without reinforcement. They can even pick this up from watching videos or cartoons, but if they are punished for such behaviour, it reduces their aggression. People learn all the time through engagement with peers and through our links to the cyber world.

LEARNING FROM OTHERS

Animals, not just humans, learn from and influence one another. This form of learning is seen among fish, birds and mammals. A very interesting study illustrates this form of learning. Monkeys living in small groups in the wild were allowed to select food coloured pink or blue. One colour for each group was contaminated with aloe to provide an innocuous, but unpleasant flavour. After a few meals, the aloe was removed from the food, but the monkeys would not eat the colour that was previously contaminated with aloe. But that behaviour transformed when monkeys from one group, say those who ate the pink food, tried to fit in with another group of monkeys, say blue-food eaters.

The pink-food-eating monkeys soon switched to eating blue food. This shows the social influence on learning, similar to what we see in humans, is an innate trend even in animals.

This form of learning from peers is a very powerful method of learning. With the advent of open access to vast educational assets and free or inexpensive communication tools, clusters of people can learn together outside as well as inside traditional educational institutions. In peer learning, the need for clarification, elaboration and reconceptualisation of material promotes learning for all parties.

A wealth of resources that promote this type of learning are now available.

The College of Exploration, incorporated in Virginia, built a global network of exploratory learning programmes about the environment, earth and ocean, and technology.

One that has drawn interest is the Uncollege in California. The founder has built a model that supplements traditional college education. The purpose is to help students who want to define their own educational track, whether in or out of the typical university and higher education models. This becomes a potential alternative in some areas by providing requisite learning at a much lower cost than colleges.

Peeragogy is another global resource for those who want to learn from one another. It provides the how-to-do-it structure for people to build their own peer learning programme. The programme has attracted participants from around the world who wish to create peer learning communities.

Finally, P2PU is a global community dedicated to learning that is open and free for all. It is meant to be learning by the people, for the people and for free. Many of the participants come from around the world. These peer settings are, in essence, time and geography independent and drawn together as learning communities.

Many of these efforts that leverage technology and the desire to learn have the potential to disrupt traditional learning structures and models, but they are more likely to supplement, transform, transplant and enhance learning for all.

Schools and institutions will have to figure out how to incorporate and adapt to this changing landscape.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Professor K Ranga Krishnan is dean of the Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School Singapore. A clinician scientist and psychiatrist, he chaired the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioural Sciences at Duke University Medical Centre from 1998 to 2009.