Rahul Gandhi’s time starts now

If you were looking for political theatre, the recent Congress party meeting in the north Indian city of Jaipur had plenty of it. The highlight of the meeting was the appointment of Mr Rahul Gandhi as Vice-President, or the official number 2, of the party.

This also signalled the intent of the Congress to project Mr Gandhi as its election mascot in the next general election scheduled for 2014. Both decisions were expected.

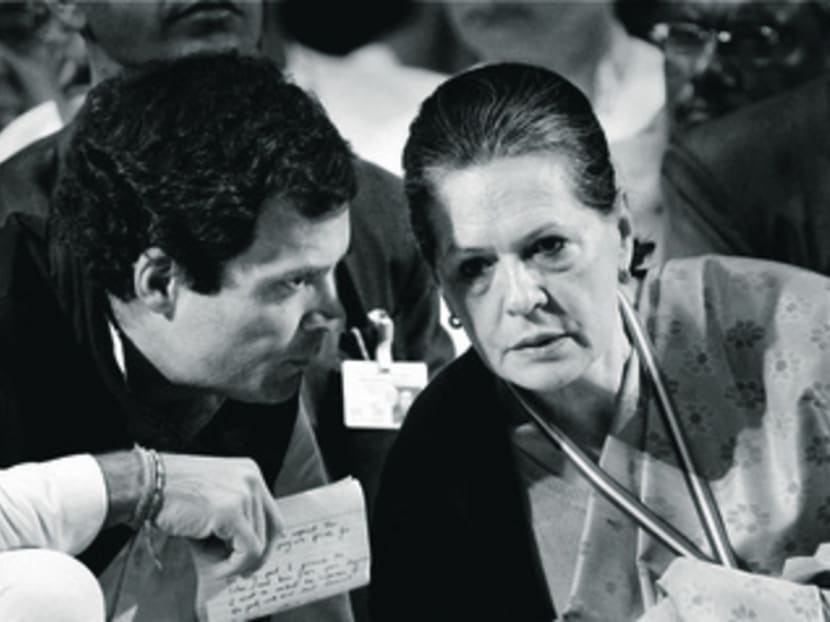

Mr Gandhi was for all purposes the second in command in the party to his mother Sonia Gandhi. Besides, it was always taken for granted in the Congress that he would be projected as the party’s candidate for Prime Minister — a chair occupied by Mr Gandhi’s great-grandfather, grandmother and father — in the coming election.

The unanimous endorsement of Mr Gandhi as Vice-President after it was proposed by a party GeneralSecretary hence was a mere formality.

It was the acceptance speech by Mr Gandhi, however, that made news.

One portion of it was very personal, recalling the bond, which has now spanned several generations, between the Nehru-Gandhi family and the Congress as well as intimate details about his growing-up years that were scarred by the assassinations of his grandmother and father. This struck an emotional chord with party members, with many of them, including hardened veterans, in tears.

The other bits of the speech were meant to resonate with the larger constituency of Indian voters. This is where he talked about the need to change the governmental and political “system” in India which he labelled as closed and unaccountable. He also raised the issue of the anger of a “young and impatient India” which is demanding change.

TOP-DOWN ORGANISATION

As speeches go, it was pretty good although it was deeply ironical that Mr Gandhi, who is emblematic of dynastic politics in India, spoke about changing a closed system.

But for all his fine words, there was precious little in his speech about what he really stands for and his plan of action, if any, to remedy the ills that he documented.

Many have compared it to a speech made by Mr Gandhi’s father and former Prime Minister, Rajiv, during the Congress’ centenary year in 1985. There, Rajiv had spoken about breaking the power brokers and cliques who dominated the party and the need to revitalise the organisation. Nearly three decades later, however, it is apparent nothing has really changed within the party.

Mr Gandhi’s speech might have given the Congress a temporary bounce, but can he turn around a party that has been battered by corruption charges, inept administration and a string of electoral losses in key states?

At present, the Congress on its own governs eight states and as part of a coalition another four. This means that of the 28 states in the Indian Union, the Congress is in government in fewer than half. That picture will change through the course of the year when elections will be held in 10 states.

What is worrying for the Congress is its marginalisation in some of India’s bigger states, including Uttar Pradesh, which sends the most number of Members of Parliament (MPs) to the Lower House of Parliament. It’s not just the current electoral scenario, however, that should be giving Mr Gandhi sleepless nights.

As a party, the Congress, since the days of Indira Gandhi, has become a top-down organisation with little internal democracy. The party’s top brass is dominated by superannuated politicians and its once-robust grassroots organisation has atrophied.

MIXED RECORD

Besides the organisational frailties of the Congress, Mr Gandhi’s record hasn’t been particularly noteworthy either. It’s been eight years since Mr Gandhi first became an MP in 2004 and later in 2007, General Secretary in charge of youth affairs for the Congress. But by steadfastly refusing to take up government office, Mr Gandhi has no public record to speak of. His performance as an MP, too, is ordinary.

The only yardstick to measure Mr Gandhi is his attempts to turn things around within the Congress. Here, too, his record is mixed. Though he was credited with the Congress’ comparatively strong showing in some states in the 2009 general election, the party’s debacle in the 2012 Uttar Pradesh election, where Mr Gandhi led the party’s campaign, was a setback. Similarly, Mr Gandhi’s efforts to regenerate the youth wing of the Congress met with some initial success but seem to have petered out of late.

What is most disturbing, however, are Mr Gandhi’s long absences from the public arena and silence on the burning issues in India, including the anti-corruption agitation in 2011 and the protests over the horrific gang rape in Delhi late last year.

Even when he has reacted, it has been too little, too late. He has sometimes given the impression that he is a reluctant politician thrust into a position not of his own making.

By staying in the background, Mr Gandhi has often escaped blame for the Congress’ poor showing in state elections, like in the polls in Gujarat last month. But now having been officially anointed as the face of the party for the next general election, he has to show that he can walk the talk.

Ronojoy Sen is visiting Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies, National University of Singapore.