The soccer mafia

The only surprise about the arrest of seven FIFA officials in a Swiss hotel in the early morning of May 27 is that it happened at all. Most people assumed these pampered men in expensive suits, governing the world’s soccer federation, were beyond the reach of the law. Whatever rumours flew or reports were made on bribes, kickbacks, vote-rigging, and other dodgy practices, FIFA president Joseph “Sepp” Blatter and his colleagues and associates always seemed to emerge without a scratch.

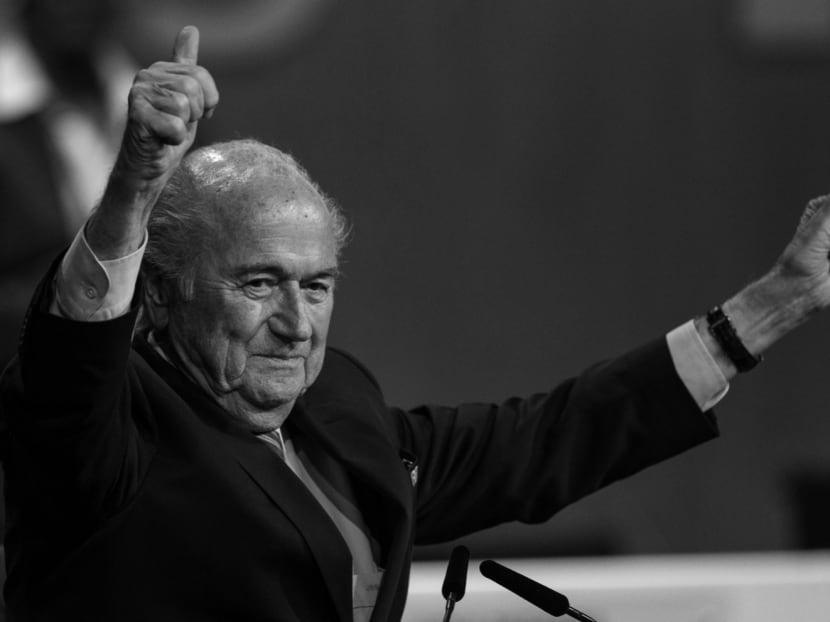

Some have likened FIFA to the Mafia, and Mr Blatter, born in a small Swiss village, has been called Don Blatterone. Photo: AP

The only surprise about the arrest of seven FIFA officials in a Swiss hotel in the early morning of May 27 is that it happened at all. Most people assumed these pampered men in expensive suits, governing the world’s soccer federation, were beyond the reach of the law. Whatever rumours flew or reports were made on bribes, kickbacks, vote-rigging, and other dodgy practices, FIFA president Joseph “Sepp” Blatter and his colleagues and associates always seemed to emerge without a scratch.

So far, 14 men, including nine current or former FIFA executives (but not Mr Blatter), have been charged with a range of fraud and corruption offences in the United States, where prosecutors accuse them, among other things, of pocketing US$150 million (S$202 million) in bribes and kickbacks. And Swiss federal prosecutors are looking into shady deals behind the decisions to award the World Cup competitions in 2018 and 2022 to Russia and Qatar, respectively.

There is, of course, a long tradition of racketeering in professional sports. American mobsters have had a major interest in boxing, for example. Even the once gentlemanly game of cricket has been tainted by the infiltration of gambling networks and other crooked dealers. FIFA is merely the richest, most powerful, most global milk cow of all.

Some have likened FIFA to the Mafia, and Mr Blatter, born in a small Swiss village, has been called Don Blatterone. This is not entirely fair. So far as we know, no murder contracts have been issued from FIFA’s head office in Zurich. But the organisation’s secrecy, intimidation of rivals, and a reliance on favours, bribes and called debts do show disturbing parallels to the world of organised crime.

One could, of course, choose to see FIFA as a dysfunctional organisation rather than a criminal enterprise. But even in this more charitable scenario, much of the malfeasance is a direct result of the federation’s total lack of transparency. The entire operation is run by a close-knit group of men (women play no part in this murky business), all of whom are beholden to the boss.

This did not start under Mr Blatter. It was his predecessor, the sinister Brazilian Joao Havelange, who turned FIFA into a corrupt and vastly rich empire by incorporating more and more developing countries, whose votes for the bosses were bought with all manner of lucrative marketing and media deals.

Huge amounts of corporate money from Coca-Cola and Adidas went sloshing through the system, all the way to the roomy pockets of Third World potentates and, allegedly, of Mr Havelange himself. Coke was the main sponsor of the 1978 World Cup in Argentina, ruled in those days by a brutal military junta.

Mr Blatter is not quite as uncouth as Mr Havelange. Unlike the Brazilian, he does not openly associate with mobsters. But his power, too, relies on the votes of countries outside Western Europe, and their loyalty, too, is secured by the promise of television rights and commercial franchises. In the case of Qatar, this meant the right to stage the World Cup in an utterly unsuitable climate, in stadiums hastily built under terrible conditions by underpaid foreign workers with few rights.

Complaints from slightly more fastidious Europeans are often met with accusations of neo-colonialist attitudes or even racism. Indeed, this is what makes Mr Blatter a typical man of our times. He is a ruthless operator who presents himself as the champion of the developing world, protecting the interests of Africans, Asians, Arabs and South Americans against the arrogant West.

Things have changed since the days when venal men from poor countries were paid off to further Western political or commercial interests. This still occurs, of course. But the really big money now, more often than not, is made outside the West, in China, the Persian Gulf and even Russia.

Western businessmen, architects, artists, university presidents, and museum directors — or anyone who needs large amounts of cash to fund their expensive projects — now have to deal with non-Western autocrats.

So do democratically elected politicians, of course. And some — think of Mr Tony Blair — turn it into a post-government career.

Pandering to authoritarian regimes and opaque business interests is not a wholesome enterprise. The contemporary alliance of Western interests — in the arts and higher education no less than in sports — with rich, undemocratic powers involves compromises that might easily damage established reputations.

One way to deflect the attention is to borrow the old anti-imperialist rhetoric of the left. Dealing with despots and shady tycoons is no longer venal, but noble.

Selling the franchise of a university or a museum to a Gulf state, building yet another enormous stadium in China, or making a fortune out of soccer favours to Russia or Qatar is progressive, anti-racist and a triumph of global fraternity and universal values.

This is the most irritating aspect of Mr Blatter’s FIFA. The corruption, the vote-buying, the absurd thirst of soccer bosses for international prestige, the puffed-out chests festooned with medals and decorations — all of that is par for the course. It is the hypocrisy that rankles.

To lament the shift in global power and influence away from the heartlands of Europe and the US is useless. And we cannot accurately predict this shift’s political consequences.

But if the sorry story of FIFA is any indication, we can be sure that, whatever forms government might take, money still rules. PROJECT SYNDICATE

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Ian Buruma is Professor of Democracy, Human Rights, and Journalism at Bard College, and the author of Year Zero: A History of 1945.