ADHD not just a childhood condition

SINGAPORE — Diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in primary school, Luke Tan (not his real name) was once branded a hopeless case by teachers and relatives.

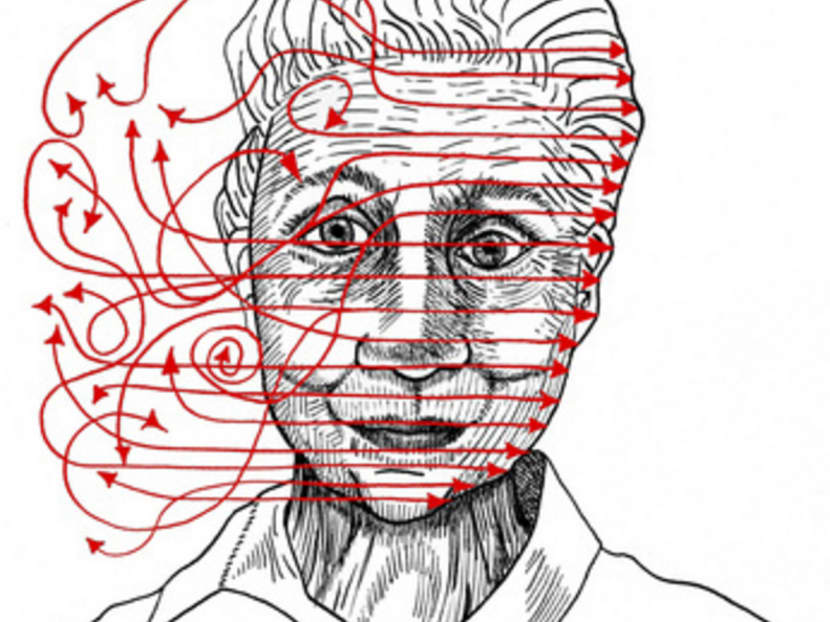

Once seen as a disorder affecting mainly children and young adults, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is increasingly understood to last throughout one’s lifetime. Photo: The New York Times

SINGAPORE — Diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in primary school, Luke Tan (not his real name) was once branded a hopeless case by teachers and relatives.

The former school dropout has come a long way since his pai kia (bad boy) days, when he would skip school and get into fights. Now an overseas law graduate, Mr Tan is preparing for his bar examinations.

While age has mellowed his ADHD symptoms, Mr Tan still finds it hard to sit still.

“Some people can study for hours. I can’t. My strategy is to take breaks in between long stretches of studying. I need to walk around and listen to music,” said Mr Tan, who requested that his real name and age be withheld.

Mention ADHD and hyperactive children come to mind. Characterised by hyperactivity, impulsive behaviour and inattention, symptoms typically begin before the age of 12, said Dr Ganesh Kunjithapatham, consultant at the Department of General Psychiatry at the Institute of Mental Health (IMH).

ADHD’s symptoms can continue well into adulthood, said the experts. When a diagnosis is made in adulthood, it probably means the individual was never diagnosed as a child, said clinical psychologist Ms Vyda S Chai at Think Psychological Services.

Some global studies suggest that up to 70 or 80 per cent of people with ADHD may not “outgrow” the neuro-developmental condition, believed to be caused by chemical imbalance in the frontal lobe of the brain that governs cognitive development, executive functioning and impulse control, said Ms Bella Chin, president of Society for the Promotion of ADHD Research and Knowledge (SPARK).

According to Dr Ganesh, a US study found that ADHD affects 2.5 per cent of the adult population in America. The same study also found that about 15 per cent of children diagnosed with ADHD will have symptoms in adulthood that require follow-ups, medication or other interventions. There is currently no data on adult ADHD in Singapore.

Last year, IMH saw 115 ADHD patients aged 19 and above. The figure is almost double from the 63 adult patients seen in 2012. Dr Ganesh attributed the increase to greater awareness of the condition in the community.

A new set of ADHD diagnostic criteria, updated in the fifth edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) released in 2013, has also made it easier to diagnose teens and adults, said Ms Chai. Some of the changes include raising the age of when symptoms can occur from seven to 12 years, as well as new descriptions on how the disorder appears in adults and teens.

“When diagnosing ADHD in adults and teens, clinicians now look back to middle childhood (around 12 years old) and the teen years for the onset of symptoms, not necessarily all the way back to childhood,” said Ms Chai.

LIVING WITH ADHD

Unlike children, whose ADHD symptoms may present as hyperactivity, adults tend to display inattentive or impulsive behaviour, said Dr Ganesh. For some people, symptoms may improve with age as the brain matures and they learn to adapt to their condition, he added.

But while ADHD may improve with age, many of those who do not receive support and intervention earlier tend to carry some of their symptoms into adulthood, said Ms Chai.

Married and working adults take up about 20 per cent of the cases that Think Psychological Services sees for assessment diagnosis, intervention or counselling for suspected ADHD in the past year. Ms Chai said these adults seek professional help when the symptoms interfere with their everyday functions, work and relationships.

“A number of adults we have seen also have substance-abuse issues or secondary symptoms such as depression and anxiety,” said Ms Chai.

Mr Tan quit school after completing his PSLE examinations. In his teens, he struggled to contain his condition while he eked out a living in the hotel industry. Medication helped to a certain extent, but he was often easily agitated when its effects wore off.

“At that time, ADHD was unheard of. People wrote me off as a troublemaker and called me all sorts of names. They could not understand what I was going through,” said Mr Tan.

A HOLISTIC TREATMENT PLAN

While medication may be able to offer immediate relief from ADHD symptoms, research has shown that this alone may not help to address the many core issues these individuals face, said Ms Chai. For instance, they may have difficulties controlling their impulses, lack organisation skills and social etiquette, or do poorly in stress management. As such, treatment for ADHD — for both children and adults — typically consists of a combination of medications and psychotherapy. Some patients may also engage coaches to help hone their soft skills, such as organisation skills, time management and personal social skills, said Dr Ganesh.

Said Ms Chai: “The idea is to help the person increase his level of function as much as possible and work on alleviating secondary conditions, such as depression, anxiety and self-esteem issues. ADHD symptoms can reduce if the person has access to the right tools and coping strategies”.

Ms Chin added that those with ADHD can maximise their potential by focusing on and developing their strengths and talents. “It will help a great deal if our education system can allow for and provide alternative paths to success besides academics in their school-going years,” said Ms Chin.

Spurred by his mother’s encouragement to channel his energy into something constructive, Mr Tan returned to school about eight years ago. He attended a foundation programme as he didn’t have an “O” level certificate, and went on to complete a diploma course before obtaining a law degree from a university in the United Kingdom.

“My mum said since I liked fighting so much, why not learn to ‘fight’ in court instead? Without her support and belief in me, I wouldn’t be where I am now,” he said.