Food-borne hepatitis E virus targets unwary travellers

SINGAPORE — A week after returning from a business trip in India Mr Harold Zhang (not his real name) developed fever, lethargy, loss of appetite and nausea. His doctor, a general practitioner, initially put it down to a simple viral infection. But the 43-year-old businessman knew something was amiss when his urine took on a tea-coloured hue and the whites of his eyes started to turn yellow.

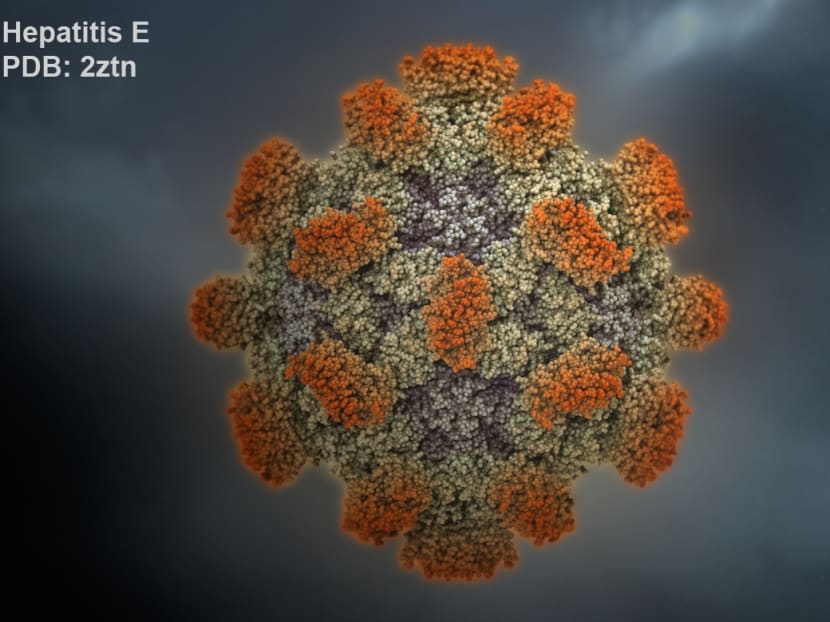

An image rendering of the Hepatitis E virus. The infection, which attacks the liver, is commonly found in developing countries that lack access to clean water and good sanitation, but cases have been reported in Singapore.

SINGAPORE — A week after returning from a business trip in India Mr Harold Zhang (not his real name) developed fever, lethargy, loss of appetite and nausea. His doctor, a general practitioner, initially put it down to a simple viral infection. But the 43-year-old businessman knew something was amiss when his urine took on a tea-coloured hue and the whites of his eyes started to turn yellow.

He then went to gastroenterology specialist Amitabh Monga about four months ago, and blood tests revealed an acute hepatitis E virus infection which he had probably picked up overseas.

The infection, which attacks the liver, is commonly found in developing countries that lack access to clean water and good sanitation, but cases have been reported in Singapore.

Last year, 85 cases were reported here according to the Ministry of Health figures.

This was lower than the 13-year (between 2004 and 2016) peak of 114 cases in 2010, but significantly higher than the 24 cases in 2004.

The rise could be due to the increasing number of visitors from countries such as India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, where hepatitis E is endemic, according to Dr Monga, a consultant at Raffles Internal Medicine Centre.

More than half of the patients in Singapore detected to have acute hepatitis E are from overseas, he said.

The rise in local cases detected could also be due to more doctors carrying out tests to check for the infection, according to infectious disease expert Leong Hoe Nam of Rophi Clinic at Mount Elizabeth Novena Specialist Centre.

A lack of public awareness of the infection may be why Singaporeans are acquiring it on overseas trips.

Despite some 20 million cases occurring worldwide each year, according to World Health Organisation (WHO), there is lower public awareness of hepatitis E compared to its more well-known cousins, hepatitis B and C.

Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver and the different letters — A, B, C, D and E — represent the five unique hepatitis viruses.

The viruses differ in various ways, including the mode of transmission and availability of a vaccine.

Types B and C, together, are the most common cause of liver cirrhosis and cancer, and lead to chronic disease in hundreds of millions of people worldwide, said WHO on its website.

Hepatitis D infections occur only in those infected with hepatitis B.

Hepatitis A and E are food-borne diseases, but the latter is mainly transmitted by drinking water contaminated with faecal matter.

Both types of viruses are endemic in most countries in the region, said Dr Leong.

“Once we step out of Singapore, the risk opens up,” he added. “Singaporeans are travelling further and further to countries with less access to clean water, but yet carry the same mentality — of how they usually live in super-clean Singapore — thus exposing themselves to infection.

“For example, they eat anything and everything they see, consume salads, half-cooked eggs and uncooked oysters or use tap water to rinse the mouth despite knowing the water is not safe to drink. The Singapore government actively screens the food we eat, but this may not be the case in other countries.”

The disease is not limited to developing nations or areas where poor sanitation is apparent.

Cases have been reported in Japan, said Dr Leong, who once encountered a local patient who contracted the infection, probably due to something she ate there.

“Contamination (during food preparation) can occur any time,” he said. “Think of it as a five-star hotel that employs a one-star kitchen helper who may not understand the level of cleanliness required to prevent transmission.”

In recent years, the United Kingdom has seen a surge in the number of infections, due to a new strain of hepatitis E from improperly cooked pork or pork products.

The bug is believed to have originated from pig farms in France, Holland, Germany and Denmark. Public Health England estimates it has affected about 60,000 people in the UK.

CLEAN HABITS ARE VITAL

Hepatitis E infection symptoms are similar to those of other forms of acute viral hepatitis — fatigue, lethargy, a low-grade fever, abdominal discomfort and jaundice (yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes), according to Dr Monga.

It can sometimes cause itching and prolonged jaundice.

Many people may be unaware that they are infected.

A large proportion of patients are asymptomatic or display mild symptoms, and may think they have a “flu-like illness”, said Dr Leong.

An infected person may unwittingly pass the infection to people around him or her, as the virus is shed in the stools and has an incubation period of up to 10 weeks.

The virus is believed to be excreted a few days before the onset of the disease, up to around three to four weeks after, according to the WHO.

“It is well-known that household (members) can fall sick after one person in the family is down with hepatitis A or E,” said Dr Leong.

Most people will make an uneventful recovery, without special treatment, within three to six weeks, said Dr Monga. After that, they usually develop immunity to the particular strain of hepatitis E. Certain groups of people including older adults, those with compromised immune systems and those with pre-existing liver diseases are at risk of more serious complications such as acute liver failure.

Hepatitis E infections have been reported to be fatal in up to one in four pregnant women in their third trimester, according to the WHO.

A hepatitis E vaccine has been developed in China, but is not available or approved in other parts of the world.

In the meantime, adopting habits in line with the “clean water, clean hands and clean food” mantra can help prevent transmission of the disease, said Dr Leong.

The WHO advises against consuming water and ice of unknown purity.

With a growing number of Singaporeans travelling every year, Dr Leong also advised getting vaccinated against hepatitis A.

Those under the age of 45 should go for two doses, recommended at six months apart.

Those above the age of 45 should do a blood test to check for an absence of immunity to the infection, before going for the vaccination, he said.