Why paternal age matters to children’s health

Sir Mick Jagger embodies what one writer has called paleo-fatherhood, or the trend of becoming a dad in later life.

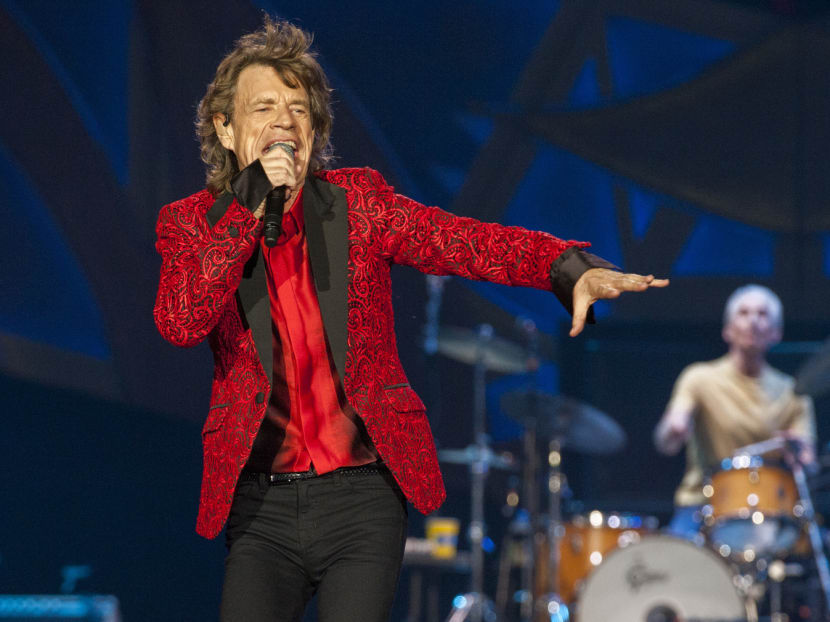

Sir Mick Jagger was 73 years of age when his eighth child was born to his 29-year-old partner, Melanie Hamrick in December last year. There has been a shift to older parenthood in recent decades. Photo: AP

Sir Mick Jagger embodies what one writer has called paleo-fatherhood, or the trend of becoming a dad in later life.

He was 73 when Deveraux, his eighth child, was born to his 29-year-old partner, ballerina Melanie Hamrick.

The Rolling Stone is an extreme example but there has been a shift to older parenthood in recent decades.

Discussion has tended to focus on women’s declining fertility, but paternal age seems to matter too.

There is fairly robust evidence that fathers who conceive in their 40s or older have children who run two to three times the usual risk of developing an autism spectrum disorder and schizophrenia.

Other studies have implicated advanced paternal age (usually defined as over 40, though different studies use different thresholds) in low academic achievement.

A paper out this month suggests that the children of both atypically young and old fathers are more likely to show unusual patterns of social development, and to end up more socially challenged than their peers.

The reasons for this are unclear, but the findings highlight the emerging association between delayed fatherhood and higher health risks for offspring.

The big question is whether this association stems from age-related genetic changes in sperm, or whether the men who become fathers later in life already have social difficulties that delay conception, which then get passed on to the next generation.

The new research was led by Dr Magdalena Janecka, from the Seaver Autism Center for Research and Treatment, at the Mount Sinai Hospital in New York.

It looked at data collected on 15,000 pairs of twins between the ages of four and 16, including social development, conduct with peers, and hyperactivity, and ruled out those already diagnosed with autism.

It found that children born to fathers aged either under 25 or over 51, were more socially skilled than their peers in their early development.

By adolescence, however, the same children had fallen behind socially.

Their findings, published this month in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, were independent of the mother’s age.

Dr Janecka concludes that “social skills are a key domain affected by paternal age ... in extreme cases, these effects may contribute to clinical disorders”.

The researchers theorise that paternal age influences how a child’s brain matures, with further study possibly shedding light on how autism and schizophrenia develop.

Scientists suggest that random genetic mutations during sperm production might explain the association.

The precursors to sperm cells are continually dividing, with each division representing the opportunity for a genetic typo, or copying mistake.

The rate of these so-called de novo mutations has been estimated to double roughly every 16 years, meaning older men shoulder many more mutations than younger men.

Others have suggested that the rate of such mutations is simply not high enough to account fully for the higher risk of psychiatric illness in the children of older fathers.

A 2016 paper in Nature by scientists from the Queensland Brain Institute concluded that “genetic risk factors shared by older fathers and their offspring are a credible alternative explanation” to the mutated sperm theory.

In other words, men who are at greater risk of psychiatric illness tend to become fathers later in life — and their children simply inherit that greater risk.

If this is the case, the biological clock does not tick as urgently for men as for women. But the science is by no means settled, partly because there are so many other factors aside from parental age — such as childhood neglect and drug use — that influence mental health.

One major study, which supports the link between paternal age, psychiatric risk and academic outcome, involved combing the data of 2.6 million Swedes. It was able to compare siblings born to the same father.

If the siblings were simply inheriting risk, paternal age would be immaterial. In fact, as paternal age rises, so does the risk of psychiatric illness and lower school grades.

“It would make sense that the effect lies in the integrity of the sperm line,” said Professor Frances Happe, an autism expert at the Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London, and a co-author of the JAACAP paper.

Men, she adds, make sperm throughout life. The production process may be vulnerable to environmental effects as well as random mutations.

Professor Adam Balen, chair of the British Fertility Society, said the study “doesn’t give a definitive answer about the biological or social causes of autism in the children of older men”.

He added: “As people in more developed economies are choosing to have children later in life, we need to understand what that might mean for the overall health and well-being of future generations.”

Prof Happe also warned that, since it is impossible to predict which men are affected, couples should not plan families around this research. In the meantime, silver-haired dads are on the rise, thanks to a collision of social trends.

Many men and women want to taste career success — and the financial stability that accompanies it — before procreating. Relatively high divorce rates are producing second broods, and reproductive science is extending the age limits to parenting that were previously set by nature.

Celebrity fathers are removing the stigma of late parenthood: Sir Paul McCartney and Clint Eastwood became 60-something dads.

There might even be advantages amid the (hypothetical) genetic gloom: Work might not compete as much; finances might be less strained. Perhaps Sir Mick had thought it through, after all. Financial Times

About the author: Anjana Ahuja is a contributing writer on science for the Financial Times.