IVF couples seek ‘embryo screening’ overseas to improve pregnancy chances

SINGAPORE — Despite shelling out over S$100,000 for multiple in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) treatments in the past six years, 43-year-old homemaker Sandy Tan’s (not her real name) attempts to start a family were unsuccessful.

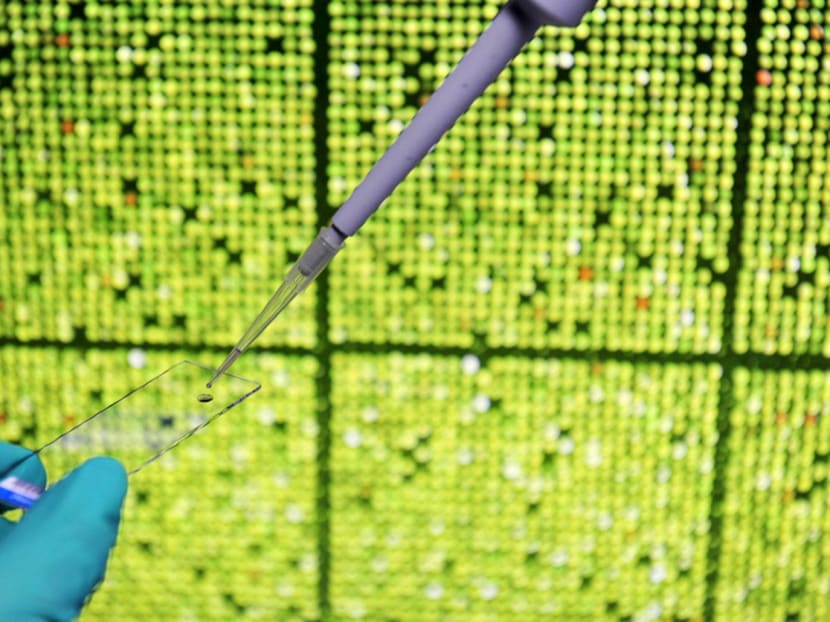

Doctors say PGS can improve pregnancy rates for those who have experienced repeated IVF failure. Photo: Reuters

SINGAPORE — Despite shelling out over S$100,000 for multiple in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) treatments in the past six years, 43-year-old homemaker Sandy Tan’s (not her real name) attempts to start a family were unsuccessful.

In a last-ditch effort to have her own biological child, Mdm Tan sought fertility treatment in Australia last year. “My husband and I wanted to find out what was wrong with our embryos, and why all our previous IVF attempts failed. We’ve experienced so much disappointment all these years,” she said.

There, she underwent pre-implantation genetic screening (PGS), an “embryo screening” technique currently not permitted in Singapore. She learnt that all her fertilised embryos were genetically flawed, which would have explained why she was unable to have a successful pregnancy through IVF.

An increasing number of Singaporeans such as Mdm Tan are turning to options abroad after exhausting fertility options here, according to a fertility centre in Singapore and another in Malaysia that offers PGS.

Dr Roland Chieng, medical director of Virtus Fertility Centre Singapore, receives three to four enquiries about embryo screening options available locally and overseas each month. The centre is part of the Virtus Health network that also operates fertility clinics in Australia and Ireland.

The centre first works with patients to explore treatment options available here; if an option is unavailable, patients are advised to explore options abroad. Alpha International Fertility Centre in Malaysia has seen about 100 couples from Singapore sign up for the screening programme in the past four years, with those who have experienced repeated IVF failures the largest group.

“Most of them are in their 40s, with several pushing 50 years old. The oldest patient we’ve seen from Singapore was a 50-year-old woman who insisted on using her own eggs, but the treatment was not successful as no quality embryos were produced,” said Dr Colin Lee, the centre’s consultant gynaecologist and fertility specialist.

Dr Lee expects the number of patients from Singapore to increase, given increasing rates of infertility and the affordability of advanced screening techniques.

PGS can help some women, say DOCTORS

Doctors say there is evidence to show that PGS can improve pregnancy rates in women who have experienced repeated IVF failure and miscarriages.

PGS is carried out with IVF and only embryos with the correct number of chromosomes are transferred into the womb, said Dr Lim Min Yu of the Division of Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility at National University Hospital Women’s Centre.

This raises the chances of pregnancy to between 70 to 90 per cent, said Dr Liow Swee Lian, Virtus Fertility Centre Singapore’s scientific director.

The overall success rate of conventional IVF is about 30 per cent, with chances of success decreasing with age, said NUH’s Dr Lim.

A woman is born with all the eggs she will ever have and, due to their decline in quantity and quality as she ages, the risk of chromosomal abnormality increases. An extra copy of chromosome 21 would mean a child with Down syndrome, for instance.

Dr Lee believes PGS should be offered to every couple who undergoes IVF. “A 39-year-old woman only has a 12 to 13 per cent chance of producing a normal embryo. What kind of pregnancy rate would you expect, after transferring it to her womb using the current practice of IVF?” he said. “Moreover, if genetic abnormalities can be prevented before the embryo is implanted and current technology allows it, why not?”

The technique is not without ethical implications, such as its potential use for gender selection by couples.

The risk of it being used to select embryos for non-medical reasons was cited by Health Minister Gan Kim Yong as a reason for the Ministry of Health (MOH) rejecting PGS requests, in a parliamentary reply last year to Nominated Member of Parliament Kuik Shiao-Yin.

Mr Gan said its effectiveness in improving the chance of live births for women with fertility problems is “unclear at present” but that his ministry would review the provision of PGS as new evidence emerges.

Responding to TODAY’s queries, the MOH said it is currently reviewing a proposal to offer PGS on a trial basis, as a pilot project at a local assisted-reproduction centre.

In Australia, the gender-selection concern has been easily overcome by not reporting the sex of the embryos, said Dr Liow.

Australia and Malaysia are among countries that do not allow the use of PGS for gender selection for social reasons, although a 2010 survey by the International Federation of Fertility Societies found that it is legal in 15 out of 104 countries, including the United States.

The most advanced PGS technology can now predict potential health risks, such as genes that increase the risk of breast or ovarian cancer, the child may have in future, said Dr Lee.

Mdm Tan is now considering options such as donor eggs and surrogacy, but some what-ifs linger.

“I wish we had learnt about PGS earlier. Perhaps we would be able to get viable embryos if we had done the screening right from the start,” she said.