Is salt really bad for the heart?

Local experts weigh in on controversy surrounding salt intake, heart disease

SINGAPORE — For decades, salt has earned a bad reputation for its negative effects on cardiovascular health. Consuming too much salt is said to raise blood pressure, a significant risk factor for stroke and heart disease, which account for one in three deaths in Singapore.

But new sodium studies have cast doubt on its harmfulness.

A review of seven studies involving over 6,000 participants found that while cutting down on salt slightly lowers blood pressure, there is no strong evidence to say that it reduces cardiovascular disease risk or death in people with normal or high blood pressure. The study was first published in the American Journal of Hypertension in 2011 and updated in 2014.

A study published last year in Jama Internal Medicine further suggests that salt might not be all that hazardous for heart health. Researchers examined records of 2,600 older adults over a 10-year period and found that salt intake had little effect on overall death and heart failure rates.

Meanwhile, findings from another study published in The Lancet this year found that while a high sodium intake is linked to a greater risk of cardiovascular disease and death in people with hypertension, a low sodium diet may also raise this risk in people with or without hypertension.

Do these findings mean it is time to shake off salt’s bad rap?

Experts told TODAY the studies are best taken with a pinch of salt. After all, for every study that downplays the risks of a high salt diet, there are others that provide solid evidence of its negative health effects.

Mr Lim Kiat, a nutritionist with the Singapore Heart Foundation, cited a review involving over 177,000 participants, which linked a high salt intake to a significantly greater risk of cardiovascular disease.

Reducing salt intake by half, from 10g to 5g per day, would lower stroke risk by 23 per cent and overall cardiovascular disease risk by 17 per cent, according to the findings published in The BMJ in 2009.

Taking into account previous well-established research findings, the evidence underpinning the World Health Organisation’s target to reduce salt intake to less than 5g per day remains indisputable, said Dr Mei-Yen Chan, senior lecturer in Food and Human Nutrition at Newcastle University (UK), Singapore.

“Most countries, including Singapore, struggle to lower their population’s salt intake levels to meet this target. Health promotion strategies to lower salt intake and reach the WHO target should not be daunted by the findings from these recent studies,” said Dr Chan.

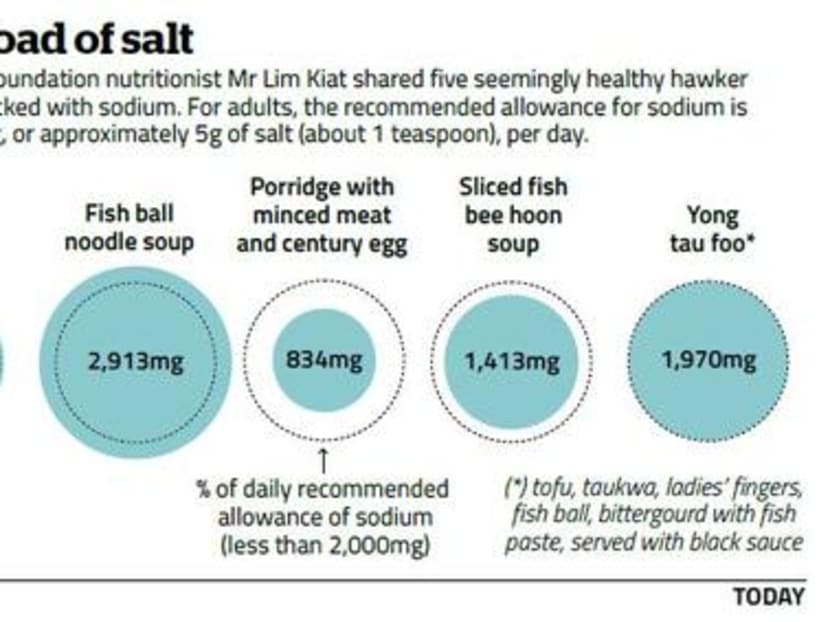

Public health strategies have focused on encouraging Singaporeans, eight in 10 of whom exceed the recommended daily salt intake, to eat less salt, said SHF’s Mr Lim. The average adult here consumes about 9g of salt per day, which is more than the recommended 5g (one teaspoon) per day, said the Health Promotion Board’s (HPB) spokesperson.

Consuming too much salt-preserved, cured or smoked food has also been linked to other diseases such as stomach and nasopharyngeal cancers, said a HPB spokesperson.

In 2014, the HPB announced its Food Strategy, an initiative to change the way Singaporeans eat at home and when they dine out.

Recently, the HPB also launched a nutrition tool kit for seniors that includes healthier eating tips such as how to use less salt when cooking at home.

“Salt is one of the main sources of sodium in the diet. There is good evidence to show that reducing sodium intake from salt and other sources helps lower blood pressure in both healthy individuals and those with high blood pressure,” said the HPB’s spokesperson.

Other sources of sodium — a type of mineral that occurs naturally in most food like meat, fruit and vegetables — include sauces, gravies, MSG and preservatives.

According to Assistant Professor Calvin Chin, a consultant at the National Heart Centre Singapore’s (NHCS) Department of Cardiology, the controversy surrounding salt and blood pressure is “unlikely to be resolved” anytime soon, in part due to the challenge of conducting research on nutritional intake.

Dr Chan said methods commonly used to assess dietary intakes, such as food frequency questionnaires and weighed food diaries, are subjected to the study participants’ recall biases, misreporting and other limitations.

“For instance, in the Lancet study, sodium excreted in the urine was used as a measure of how much salt the individual had taken. Can sodium in urine reflect how much sodium we take?” said Asst Prof Chin.

“However, one message is clear and well-established; if you have hypertension, heart failure or kidney problems, you should avoid a high salt intake.”

That said, cutting out too much sodium from the diet is not an option either, as the body needs an appropriate amount to function properly. Extremely low sodium levels can be harmful and even deadly, but this is not common in people who maintain a balanced diet, and is usually seen in the elderly and those on certain medications that affect the body’s sodium levels, he added.

Ultimately, the experts emphasised that there is more to managing a healthy heart than just limiting salt intake. “A balanced and healthy diet, along with an active lifestyle, are also essential in keeping the heart healthy,” said Mr Lim.