Another Earth might be near, a mere 25 trillion miles away

NEW YORK — Another Earth could be circling the star right next door to us.

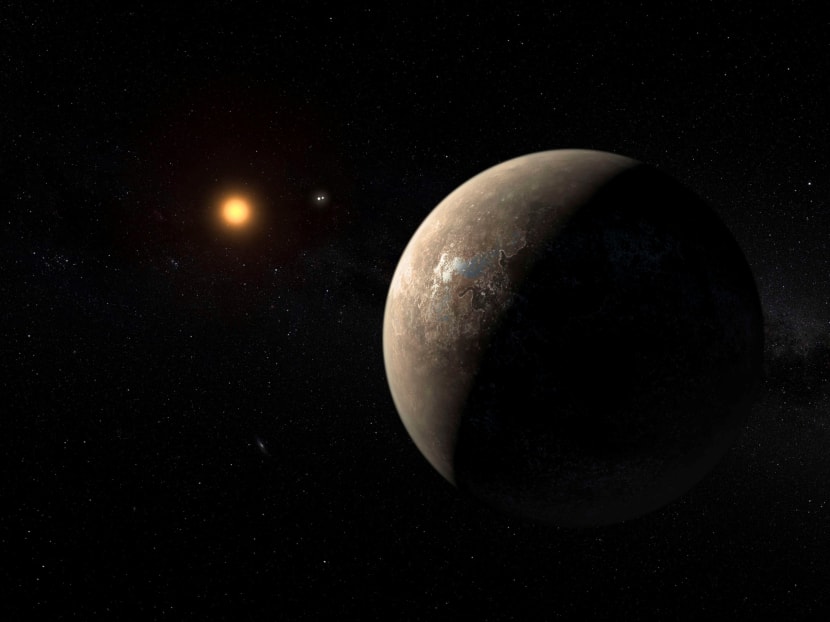

The planet Proxima b orbiting the red dwarf star Proxima Centauri, the closest star to our Solar System, is seen in an undated artist's impression released by the European Southern Observatory on Aug 24, 2016. Photo: ESO via Reuters

NEW YORK — Another Earth could be circling the star right next door to us.

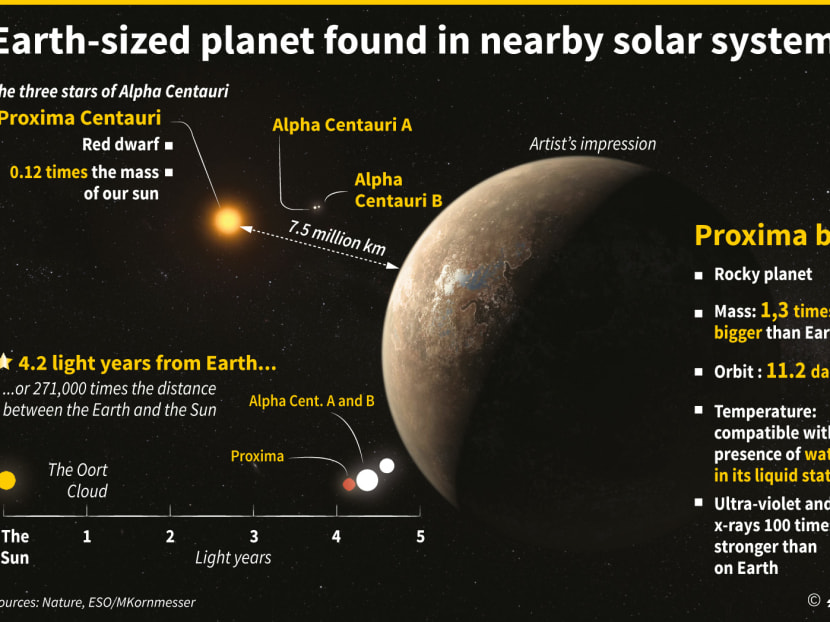

Astronomers announced on Wednesday (Aug 24) that they had detected a planet orbiting Proxima Centauri, the closest neighbour to our solar system. Intriguingly, the planet is in the star’s “Goldilocks zone,” where it may not be too hot nor too cold. That means liquid water could exist at the surface, raising the possibility for life.

Although observations in recent years, particularly by NASA’s Kepler planet-finding mission, have uncovered a bounty of Earth-size worlds throughout the galaxy, this one holds particular promise because it might someday, decades from now, be possible to reach. It’s 4.2 light-years, or 25 trillion miles, away from Earth, which is extremely close in cosmic terms.

One astronomer likened it to a flashing neon sign.

“I’m the nearest star, and I have a potentially habitable planet!” said Dr R Paul Butler, an astronomer at the Carnegie Institution for Science and a member of the team that made the discovery.

Dr Guillem Anglada-Escud, an astronomer at Queen Mary University of London and the leader of the team that made the discovery reported in the journal Nature, said, “We know there are terrestrial planets around many stars, and we kind of expected the nearby stars would contain terrestrial planets. This is not exciting because of this. The excitement is because it is the nearest one.”

Beyond the planet’s size and distance from its parent star, much about it is still mysterious. Scientists are working off computer models that offer mere hints of what’s possible: Conditions could be Earthlike, but they could also be hellish like Venus, or cold and dry like Mars.

There is no picture of the planet, which has been designated Proxima b. Instead, Anglada-Escud and his colleagues detected it indirectly, studying via telescope the light of the parent star. They zeroed in on clocklike wobbles in the starlight, as the colours shifted slightly to the reddish end of the spectrum, then slightly bluish. The oscillations, caused by the bobbing back-and-forth motion of the star as it is pulled around by the gravity of the planet, are similar to how the pitch of a police siren rises or falls depending on whether the patrol car is travelling toward or away from the listener.

From the size of the wobbles, the astronomers determined that Proxima b is at least 1.3 times the mass of Earth, although it could be several times larger. A year on Proxima b — the time to complete one orbit around the star — lasts just 11.2 days.

Although the planet, lost in the glare of the star, cannot be viewed by current telescopes, astronomers hope to see it when the next generation is built a decade from now.

And the planet’s proximity to Earth gives hope that robotic probes could someday be zooming past the planet for a close-up look. A privately funded team of scientists and technology titans, led by the Russian entrepreneur Yuri Milner and the theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking, have announced Breakthrough Starshot Initiative, a project to develop and launch a fleet of iPhone-size spacecraft within two to three decades. Their proposed destination is the Alpha Centauri star system, which includes two larger sunlike stars in addition to Proxima Centauri.

“We will definitely aim at Proxima,” said Dr Avi Loeb, a Harvard astronomer who is chairman of an advisory committee for Breakthrough Starshot. “This is like finding prime real estate in our neighbourhood.”

This newly discovered planet is much closer to its parent star, about 5 million miles apart, than Earth is to the sun, 93 million miles. Even Mercury, the innermost planet of our solar system, is 36 million miles from the sun.

While Proxima b might be similar to Earth, its parent star, Proxima Centauri, is very different from the sun. It is tiny, belonging to a class of stars known as red dwarfs, with only about 12 percent of the mass of the sun and about 1/600th the luminosity * so dim that it cannot be seen from Earth with the naked eye.

Thus Proxima b, despite its closeness to the star, receives less warmth than Earth, but enough that water could flow on the surface. Whether the planet has liquid water or an atmosphere is “pure speculation at this point,” Dr Anglada-Escud said in a news conference.

If the planet formed close to the star, it could be dry and airless, but it might also have formed farther out and migrated inward to its current orbit. It is also possible that the planet formed dry and was later bombarded by comets or ice-rich asteroids.

“There are viable models and stories that lead to a viable Earthlike planet today,” Dr Anglada-Escud said.

Even if it is habitable, scientists studying the possibility of life elsewhere in the universe spiritedly debate whether planets around these red dwarfs are a promising place to look.

Small stars are more erratic, especially during their youth, and eruptions off the star’s surface could strip away the atmosphere from such planets. Levels of X-rays and other high-energy radiation bombarding the planet would be 100 times that on Earth, the scientists said.

The close orbit suggests that the rotation of the planet would probably be gravitationally locked by the star’s pull. Just as the same side of the moon always faces Earth, one side of Proxima b is probably eternally bright, always facing the star, while the other is ever dark.

Additional visible light observations further convinced the scientists that they were not being fooled by variations in the star itself erroneously mimicking the presence of a planet.

The discovery was more than a decade and a half in the making. Dr Michael Endl, an astronomer at the University of Texas and one of the authors of the Nature paper, peered at Proxima Centauri for eight years beginning in 2000, looking for hints of a planet.

“At that time, I didn’t see anything highly, highly significant,” Dr Endl said in an interview. “Then we published our data and moved on.”

Later, Dr Anglada-Escud, analysing data from a different instrument on a different telescope, found inconclusive hints of a planet. He reached out to Dr Endl to reanalyse the earlier data, and he also spearheaded the Pale Red Dot project, which tried to observe Proxima Centauri every day for two months earlier this year.

The new observations clearly revealed the 11.2-day period of the planet, and the signal matched what Dr Anglada-Escud had suspected earlier. It also matched a signal that was hidden in the noise of Dr Endl’s data, which was lower in precision and observed Proxima Centauri only once a week or so, not every day.

There are hints of perhaps another planet, perhaps more, but those hints are still ambiguous, the scientists said.

The discovery could provide impetus for planet-finding telescopes. Dr Ruslan Belikov of the NASA Ames Research Center in Mountain View, California, has proposed a small space telescope costing less than $175 million (S$237.2 million) dedicated to the search for planets in Alpha Centauri. While it would not be powerful enough to spot Proxima b, its existence would give more confidence that terrestrial planets also orbit the two sunlike stars there.

“It just raises the public awareness there’s a new world just next door,” Dr Belikov said. “It’s a paradigm shift in people’s minds.” THE NEW YORK TIMES