Ecological planning ‘can help palm oil, forests co-exist’

SINGAPORE — The palm oil business need not grow at the expense of vast stretches of forests, two scientists are arguing in a book that aims to inject nuance into a sometimes-polarising topic.

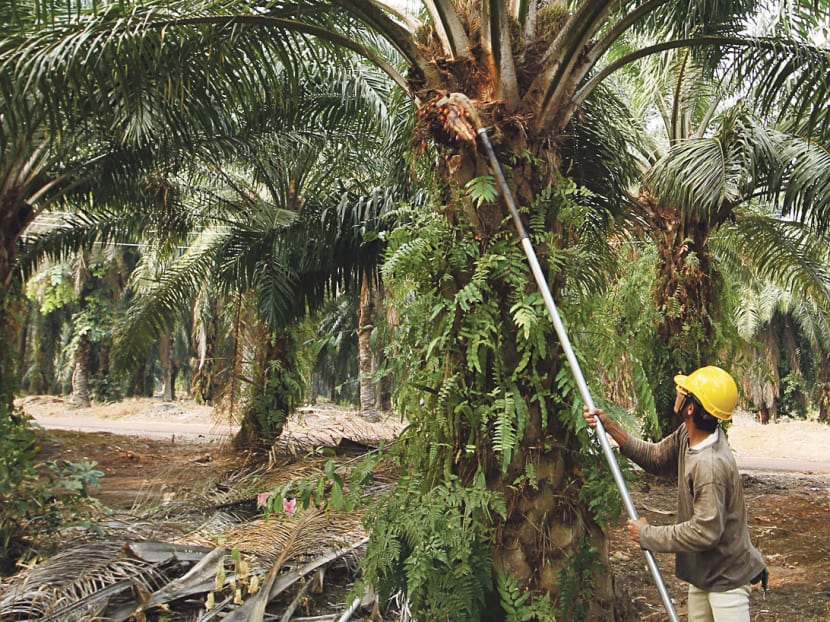

A worker harvesting oil palm fruit in Johor. Ramping up production in existing plantations through the use of improved seeds and well-planned fertilisers is important.

Photo: BLOOMBERG

SINGAPORE — The palm oil business need not grow at the expense of vast stretches of forests, two scientists are arguing in a book that aims to inject nuance into a sometimes-polarising topic.

But any expansion of the palm oil industry must include intensified use of existing plantations without damaging the environment, avoid development in areas of high conservation value, and respect the rights of indigenous people, among other strategies, they say.

The book, Palms of controversies: Oil palm and development challenges, authored by biologist Alain Rival and agricultural economist Patrice Levang, has been newly translated into English and published by the Centre for International Forestry Research.

Palm oil is used in many household products and in food manufacturing, but the industry has been in the spotlight for some haze-causing fires that have occurred on palm oil concessions. Indonesia and Malaysia supply about 87 per cent of the world’s palm oil. While viewed as a serious ecological threat by environment non-governmental organisations, oil palm is also seen as a miracle plant by the agro-food industry for its high oil yield, compared with other crops such as sunflower or rapeseed.

Yet, the relationship between palm plantations and deforestation is “neither direct or automatic”, argued Dr Rival and Dr Levang, noting that only a portion of deforested land has been converted into palm plantations.

Out of 21 million ha of primary forest that disappeared in Indonesia between 1990 and 2005, no more than 3 million have been developed into palm plantations, they wrote. However, the link has been more direct in “new frontier areas” such as Borneo, where nearly 30 per cent of primary forests destroyed were planted with oil palm.

“The problem is not the oil palm but the way people have chosen to exploit it,” they wrote.

The appeal of forests to big producers lies in the relatively free access to these areas, and the timber, they said. To secure land in areas already cleared would entail negotiations with multiple smallholders and add to the cost of the transaction, while lumber available for exploitation can cover a large part of the costs of operations.

Developing sustainable plantations

Among the ways plantations can be developed without destroying vast tracts of tropical forests is to have systems that identify and prevent areas with high carbon stock from being converted. Areas near rivers, hill tops and very steep slopes should also be avoided, and care should be taken to connect the different conservation zones.

But such “ecological planning” requires technical knowledge and additional expenses, and the financial and legal incentives to do so are still too low for most companies, noted the authors. “The market dominated by the emerging countries is more interested in cheap oil than ‘clean’ oil and the weak governance in most of the countries where the major companies are active tends not to respect legislation (when this exists at all),” they wrote.

Ramping up production in existing plantations, through the use of improved seeds and well-planned fertilisation, is important. Malaysia has an average national yield of less than four tonnes per hectare, for instance, which remains far below the top yields of six to seven tonnes per hectare in some plantations in the region, the authors said. Headway is also being made in the composting of organic waste and recycling of oil mill effluents, which can be used as organic fertilisers.

But a key obstacle to this strategy, is the transfer of innovation to smallholders, they said.

Both authors are senior research officers from French public research institutions. Dr Rival’s organisation, CIRAD, which works with developing countries to tackle agricultural and development issues, is 80 per cent funded by the French government with marginal contributions by private stakeholders, including the palm oil industry. Dr Levang’s institution, IRD, is publicly funded.

“The book was aimed at reaching the general public and to be informative on real facts and challenges in order to help in forging a balanced and clear opinion about this controversial topic,” Dr Rival told TODAY via email. “We believe that ongoing initiatives for the sustainable production of palm oil provide an interesting way forward, although they presently need and will need more and more accurate and shared results and decision tools from collaborative research.”

Contacted by TODAY, environmental group Greenpeace’s global palm oil coordinator Suzanne Kroger agreed that “it’s not the crop that should have a negative image, (but) the way it’s currently being produced and also the way currently concessions are being handed out”.

“We also think it doesn’t have to be that way,” she said, adding that Greenpeace is among the non-governmental organisations working with some palm oil producers to be held to higher standards.