Making life easier for people with kidney disease

SINGAPORE — The last four years have been tiresome for 62-year-old Ms Cheong Lee Fah, who has had to make trips to the dialysis centre every other day after she was diagnosed with kidney disease. And with the recent implant of a vascular graft — a soft plastic tube — into her arm to help with the blood flow for her haemodialysis sessions, Ms Cheong has to make two extra trips to the doctor every year to check on it.

SINGAPORE — The last four years have been tiresome for 62-year-old Ms Cheong Lee Fah, who has had to make trips to the dialysis centre every other day after she was diagnosed with kidney disease. And with the recent implant of a vascular graft — a soft plastic tube — into her arm to help with the blood flow for her haemodialysis sessions, Ms Cheong has to make two extra trips to the doctor every year to check on it.

Her chief worry, said the National Kidney Foundation (NKF) beneficiary, is the greater financial burden as the costs for such medical complications are not subsidised. After countless hospital admissions over the last few years, “I’ve lost count of my medical bills”, she said. “I simply cannot afford because I am not working now.”

To help such patients, vascular specialist Dr Benjamin Chua teamed up with scientists from the A*STAR Institute of Microelectronics to build a device that could result in patients doing away with these routine checkups.

“There are a lot of these patients, and sometimes they come to let us have a look to say that the blood flow is good, and that they can go home,” he said, noting that bills for each check could cost anything between S$400 for an ultrasound test to S$1,000 for a computerised tomography (CT) scan.

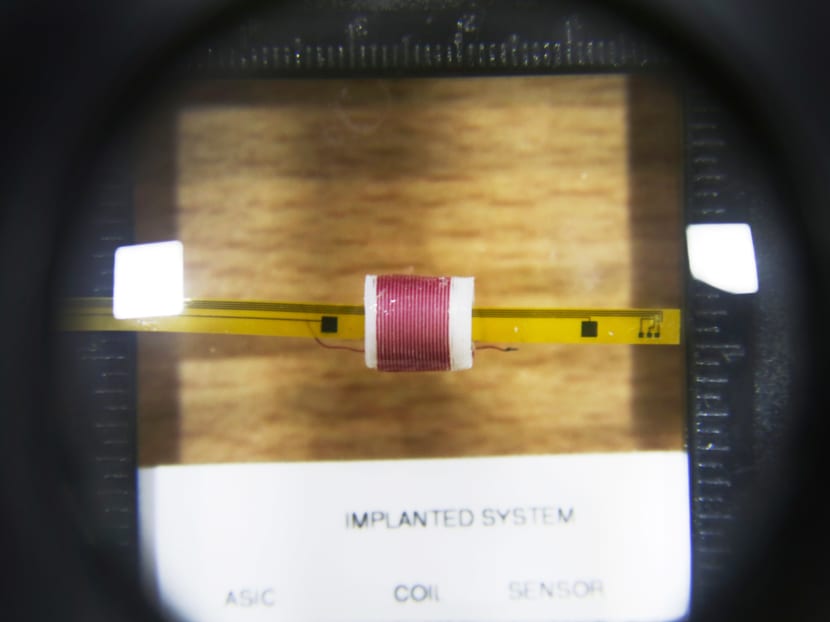

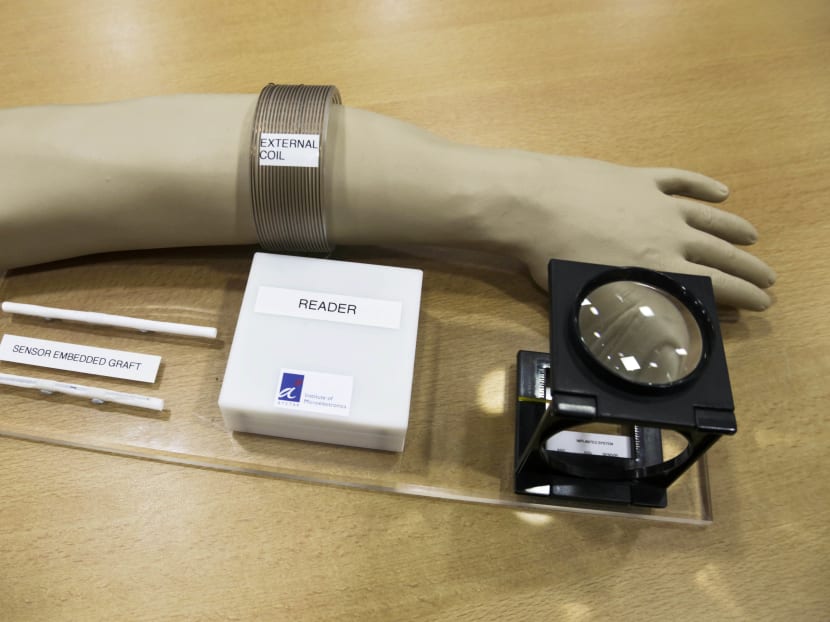

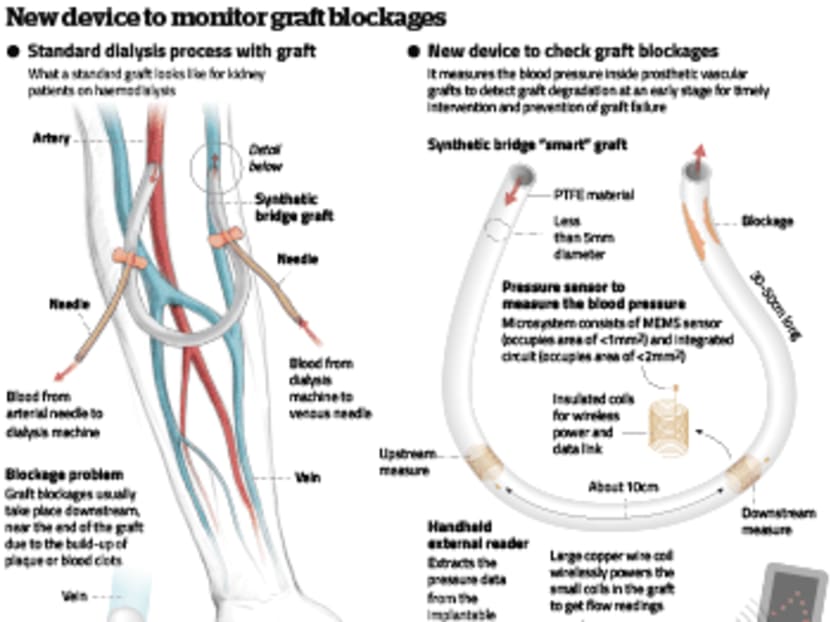

The team built a “smart” graft with tiny electronic sensors at two points to measure the blood flow through the graft. In a minute-long process, all patients would need to do is insert their limb with the graft through a handheld reader to find out the flow status.

(Click to enlarge)

The technology can also be used on those with prosthetic grafts to bypass diseased or clogged blood vessels.

“The flow rate is a surrogate of how well the graft is doing — whether it is narrowing,” said Dr Chua. “If it (the graft) gets narrower and narrower, the flow rate starts dropping and this makes dialysis difficult and inefficient.” With “real-time” readings, any blockages can be monitored and detected earlier — lessening the need for expensive scans on a regular basis.

After three years of development, scientists are now making the final tweaks before they apply for approval to start clinical trials. “So far, we have primary results and it looks promising,” said Dr Chua, a senior consultant and medical director at the Vascular & Interventional Centre at Sincere Healthcare Group. The project is expected take another three to four years before it reaches the market.

The NKF, which is not involved in the project, said it looks forward to the outcome of the clinical trials. “If the new technology with sensors allows easy, frequent and accurate measurement of access flow, it will be a real breakthrough,” said NKF medical director Dr Mooppil Nandakumar. “This will allow early intervention to prevent graft failure and hospitalisation, and reduce cost of medical care.”

Out of the 2,800 haemodialysis patients the NKF oversees, about 8 per cent of them have to rely on a graft for their haemodialysis treatments. There are about 6,000 patients undergoing dialysis in Singapore.

Ms Cheong said she welcomed any device which could lower the costs to a kidney patient.

BUILDING THE ‘SMART’ GRAFT

In a Polytetrafluoroethylene graft, usually about 30-50cm long, A*STAR scientists led by Dr Tan Ee Lim implanted two silicon-based sensors about 10cm apart: One to measure upstream pressure and another to measure downstream pressure.

The insulated copper coils that line the circumference of the graft allow for communication with an external reader. Dr Tan said tissue heating during the scan could be a risk, and the team had reduced the power consumption of the chip to 12.6mW. The external reader transmits 600mW to power the chip — over 8,000 times milder than the power used by a wireless Internet router.

Dr Alex Gu, director of the miniaturised medical devices programme at A*STAR, said the sensor is “totally passive” and works on “power transfer” from a data reader. To ensure the device can be detected under layers of human tissue, the team worked to increase the efficiency of the power transfer.

Inserting a smart graft is expected to be slightly more costly, said Dr Chua. He said a standard graft costs between S$1,500 and S$3,000.

“It is too early to say, but I think 10-20 per cent of a premium would be very acceptable,” said Ms Rachel Hong, from the National University of Singapore’s Medical Engineering Research and Commercialisation Initiative team tasked to pass the device through regulatory hurdles.

The research team also wants to develop a phone app for patients to monitor flow readings, with coloured indicators to show how well a graft is doing. “If they regularly check this, and the machine keeps going green, and the flow is good, then maybe (they) don’t need to come and see a doctor so often anymore,” said Dr Chua. “We also solve the problem of having too many patients in the hospitals.”

Team member Dr Michael Ho added: “It’s (also) about the quality of life earned.”