Art review: National Gallery Singapore’s permanent exhibitions

How does an art museum tell the stories of both a nation and a region?

How does an art museum tell the stories of both a nation and a region?

It’s a pretty colossal task that the new National Gallery Singapore has taken upon itself to do, across two permanent galleries that, once the fanfare surrounding its opening dies down, would primarily be the reason for visitors to return time and again.

And they should. The exhibitions Siapa Nama Kamu? and Between Declarations And Dreams at the DBS Singapore Gallery and UOB Southeast Asia Gallery, respectively, offer plenty of exceptional works to engage viewers of all sorts — or, at least, incite some kind of reaction. (During my latest visit, a teenager struck up a conversation, out of the blue, about a painting of a kampung house at the Singapore section. A couple of hours later, I overheard a woman muttering “I don’t have patience for this” at the South-east Asian contemporary art section. As for the issue of museum etiquette, let’s set that aside for another day.)

Meanwhile, how do the exhibitions, which will be up for five years, fare as shows as a whole?

SIAPA NAMA KAMU?

It’s essentially the same trajectory for both shows, offering a meaty presentation of art from the 19th century onwards. And we get a substantial overview of the art produced and the art movements that were born in parallel to (or as a reaction to) social and political contexts.

The results, however, are markedly different. Simply put, it is way easier to make sense of the art of a young, anal-retentive nation than that of a super-chaotic, super-diverse region.

Siapa Nama Kamu? flows smoothly: From its starting point of an 1865 engraving of a tiger leaping out of a forest to interrupt road surveyors (and its modern Singapore story-meets-Sang Nila Utama’s own mythic feline encounter allusions in this context), we encounter the Nanyang artists and their idyllic visions, before segueing into the competing schools of thought of the social realists of the Equator Art Society and the abstractionists of the Modern Art Society, and, finally, ending up with the contemporary artists from the 1980s onwards.

An exhibition of such scale offers perspective: The much-lauded 1952 trip to Bali that supposedly gave birth to the East-meets-West style of the Nanyang folks is presented as transitional rather than central (it gets a dark red corridor where the aptly titled The Ferry by Chen Wen Hsi is a central work).

But art histories are never meant to be completely linear, of course, and there are some surprises. Behind the social realists-versus-abstract artists drama is a somewhat hermetic section on Chinese ink painting. Popping up amid the Nanyang works’ rural imagery are photographs of modern Singapore. Teo Eng Seng’s The Net, which features, well, a net, feels like nudge-wink conceptual piece amid the more conventional artworks of its time.

Over at the contemporary art section, copies of the short-lived but important arts journal Forum On Contemporary Art And Society make a well-deserved cameo. But despite having so much crammed into one room (perhaps too much), the absence of one particular piece is rather glaring.

While there are works that responded to the controversy surrounding performance art (and the removal of its funding), the piece at the centre of it all, Josef Ng’s Brother Cane performance in 1993, is not to be found. Given its significance in the story of Singapore art, this is a rather unfortunate omission.

BETWEEN DECLARATIONS AND DREAMS

It’s a lot trickier making sense of the South-east Asian show, which is certainly under scrutiny not just in Singapore but in the region: When the National Gallery announced it would be housing South-east Asian works, more than a few eyebrows were raised at this bold — and for some, presumptuous — gesture.

Granted it’s not the first time Singapore has played “playground leader” — a couple of years back, the Singapore Biennale took an ambitious look at the region, resulting in an explosion of diversity that was somewhat chaotic in nature. But that chaos was part of the fun. Besides, it was merely a snapshot of contemporary art practice in the here and now.

But what happens when you cram into one show art from all these different countries with their diverse histories, aesthetic developments, politics and cultures, spread across a longer timeframe?

There’s a sense of Between Declarations And Dreams being a valiant effort to try and weave together disparate art scenes into sections that make sense. Sometimes it feels odd, like a room that brings together 19th century European-influenced masterpieces from Indonesia and the Philippines, and court art works from Thailand and Myanmar.

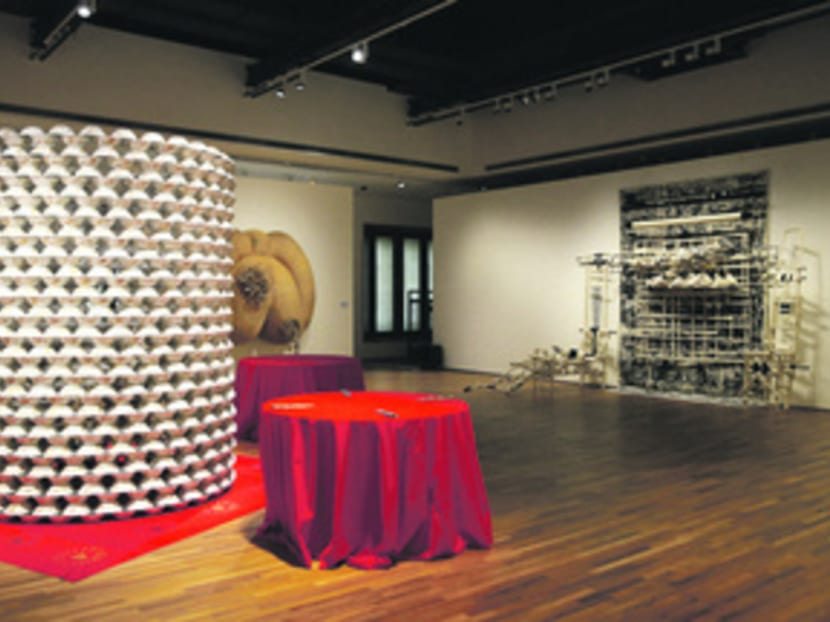

Other times, though, it just clicks wonderfully: The sections on post-World War II independence movements exude a sense of vibrancy and energy, depicting a region in a state of flux. Everyone’s doing their own thing, responding to specific situations in their own countries, but there is a bigger overarching picture, too. Ditto the section on contemporary art, where the language of the times asserts itself robustly and everything explodes in the same way that it did during the Singapore Biennale in 2013.

At best, any attempt to frame in neat terms art production from a region this messy is provisional. And once I got into that mind-set, it was easier to appreciate the significance of this motley group of artists’ forays into conceptualism, performance and installation as a response to their own specific experiences.

Unlike the condensed history of Singapore art in Siapa Nama Kamu?, Between Declarations And Dreams’ “centre” we call South-east Asia does not completely hold. It shouldn’t be unexpected and, perhaps, that’s also for the better.

The National Gallery Singapore’s two-week opening celebrations continue until Sunday. Complimentary entry by tickets only during this time, at http://tickets.nationalgallery.sg. Opening hours is from 10am to 7pm (Mon to Thur) and 10am to 11pm (Fri, Sat and Sun).