Art review: After Utopia

SINGAPORE — In 1516, the philosopher Thomas More coined the word “utopia” to describe an idealised society living on an island. He could not have predicted that, nearly half a millennium later, there would be an actual island state that some circles consider the epitome of his imagined community.

SINGAPORE — In 1516, the philosopher Thomas More coined the word “utopia” to describe an idealised society living on an island. He could not have predicted that, nearly half a millennium later, there would be an actual island state that some circles consider the epitome of his imagined community.

Singapore’s status as a kind of poster child for the utopian dream forms an interesting backdrop to the Singapore Art Museum’s (SAM) newest show, After Utopia.

Comprising 20 works from 18 artists, who are primarily from South-east Asia, the exhibition asks some rather timely questions about our ideas of the perfect world or society — Singapore, of course, is in the middle of a 50th year soul-searching experience, but it is not the only post-World War II country pondering its place in the world now. The European Union is being challenged by issues of immigration and strained economies, and closer to home, the region has been in a pretty shaky situation as well. (It is no wonder, then, that this year’s Singapore International Festival Of Arts also addresses similar “post-utopian” questions with the theme Post-Empires.)

It is easy to get overwhelmed by such a big topic, but SAM curators Tan Siuli and Louis Ho do well in condensing and simplifying the experience with four distinct sections.

There is a small narrative going on in the two wings downstairs, where opposing images of utopia — the Garden and the City — are seemingly pitted against each other.

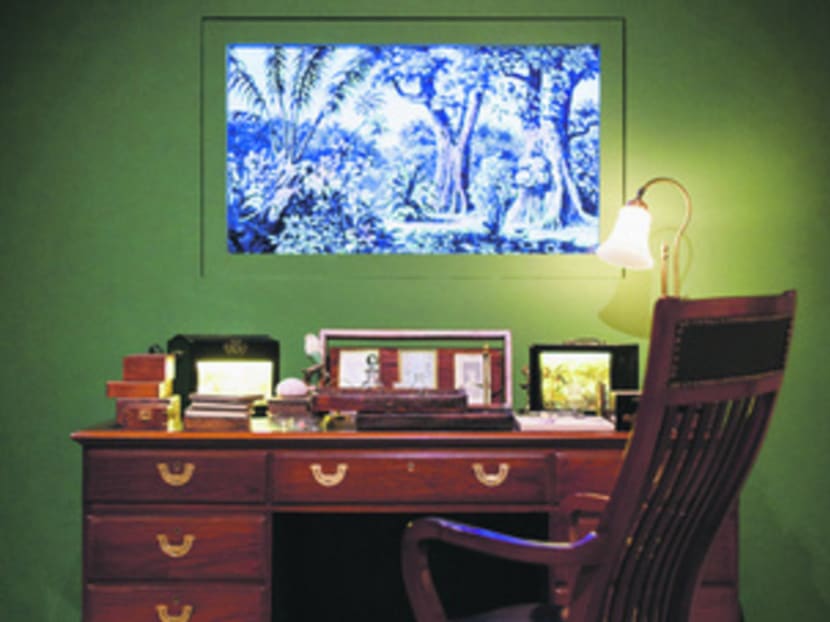

In the former, Ian Woo’s painting of an unkempt green scenery eases us into the world of former colonial masters who saw the countries they occupied as idyllic Edens — Donna Ong’s meticulously constructed desk installation, which mimics that of a colonial adventurer, is directly opposite maps of Java and West and East Asia from the time of Stamford Raffles and Walter Raleigh. But nearby is a fierce rebuke by Maryanto’s charcoal mural, a dark, barren Indonesian landscape ravaged by mining and gas drilling. The harsh present-day reality it addresses is in stark contrast with the lush vision of the colonial past.

The exhibition’s most famous (and controversial) work also plays with past-present tensions in its own imagined “garden”. Agus Suwage and Davy Linggar’s Pink Swing Park comprises a pink swing made from a rickshaw in a middle of a room with images of two naked Indonesian personalities playfully cavorting and posing in a tropical forest setting. Back in 2005, the installation had caused a media storm during the Jakarta Biennale, after an Islamic fundamentalist group protested elements of nudity. But it is its critique of artificiality, of man-made “gardens”, that justifies its presence here.

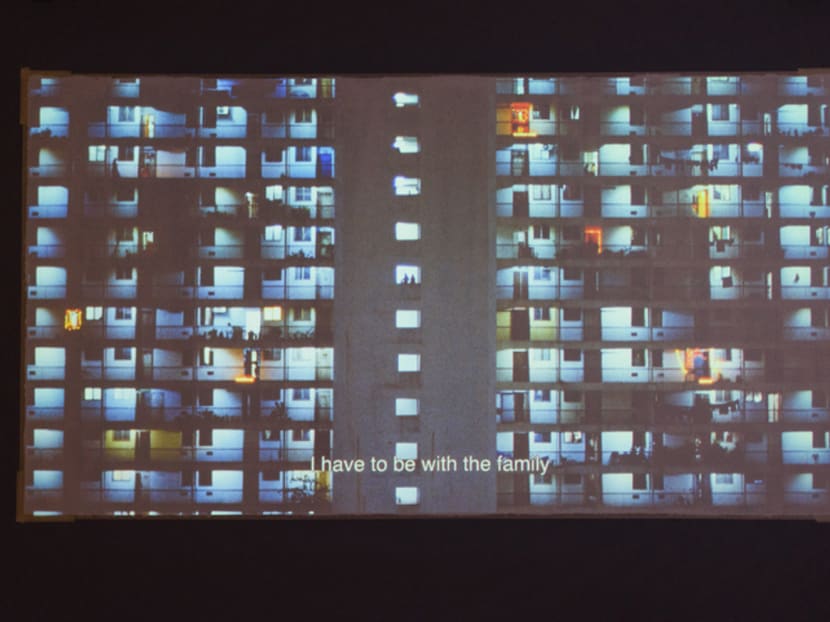

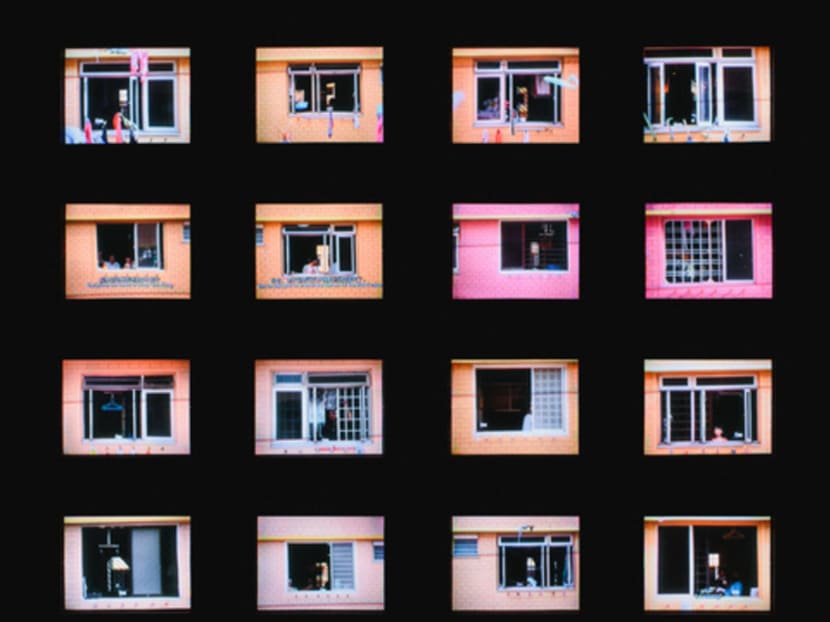

Urban life, meanwhile, rears its head next door — voyeuristic impulses and cramped living conditions are addressed in somewhat similar video works that centre around housing blocks in Singapore (Shannon Lee Castleman) and Malaysia (Chris Chong Chan Fui), and in Gao Lei’s peek-a-boo metal cabinet.

Meanwhile, Made Wianta creates a monument to pollution — a huge sculpture comprising welded motorcycle mufflers that echo, in its order-in-chaos form, the mess of Indonesia’s traffic.

These works, perhaps, are the closest one gets to our cliched images of urban dystopia (in Asia). In Tang Da Wu’s installation you see a rejection of it. Primarily a simplified map of the Sembawang area painted on a wooden platform, it is a plea for a return to the rural — that area, after all, was where The Artists Village, the art collective he founded in the ’80s, began, surrounded by chickens.

From small narratives, After Utopia takes on the idea of grand narratives upstairs, with a room that critiques the big utopian ideologies of multiculturalism and communism.

Parental bickering is compared with Malaysia’s current social and political instability in Anurendra Jegadeva’s installation, which comprises an altar-cum-wedding dais and rice mats featuring the faces of the country’s prime ministers.

Communism has been put up as the biggest grand narrative that has supposedly failed in the 20th Century and here it is given the proverbial smackdown in two works. Shen Shaomin offers what seems to be a wake, featuring communist and socialist biggies such as Lenin (and a barely breathing Fidel Castro joins in, seemingly on his deathbed). Vietnamese collective The Propeller Group, meanwhile, employed an agency to create a commercial for a so-called “new communism”. While it purportedly attempts to highlight the so-called essential values of these political systems while removing the stigma attached to it by having an all-white, all-smiles campaign, one cannot help but see it as simply smug criticism — this is advertising, the ultimate signpost of capitalist consumerism, appropriating the enemy.

But lest we forget, capitalism, too, is a utopian grand narrative whose promises are being undermined with more frequency than ever before, if you go by the economic upheavals in Greece and Spain or the Occupy movement. It initially seems as if After Utopia has given it a free pass, if not for one of the show’s two “standalone” and most eye-catching works (the other being Yudi Sulistyo’s fighter jet carcass made of cardboard).

Kawayan de Guia’s series of disco balls in shape of bombs that hang inside the museum’s chapel space is almost an accidental critique — its most recent version was set up at the Philippine Stock Exchange building, symbolically evoking destruction amid the ebb and flow of financial crises worldwide.

After Utopia’s stance on these grand narratives is clear — they are failed or failing systems and ways of thinking. Whether you agree with it or not, it offers perhaps the obvious counterpoint — a return to the personal.

The final section contains a documentation of Svay Sareth’s journey from Siem Reap to Phnom Penh, dragging a heavy metal sphere as both a physical and mental journey, as he grapples with the horrors of his (and Cambodia’s) tragic past. The meditative slant continues in Kamin Lertchaiprasert’s installation of 366 small wooden sculptures, which he had carved one for every single day. Utopia, the exhibition seems to whisper, is all in the mind.

After Utopia runs until Oct 18 at the Singapore Art Museum. For more details, visit http://www.singaporeartmuseum.sg/