From studio to museum: A painting's journey

SINGAPORE — When the magnificent-looking National Gallery Singapore opens to the public tomorrow (Nov 24), visitors will most certainly be seeing some of the best works of art from Singapore and the region.

SINGAPORE — When the magnificent-looking National Gallery Singapore opens to the public tomorrow (Nov 24), visitors will most certainly be seeing some of the best works of art from Singapore and the region.

Spread across the museum’s two permanent galleries alone are more than 800 pieces, each with its own story to tell.

So just how does one artwork go from simply being a niggling of an idea in an artist’s mind to a final product that can capture a viewer’s imagination as it hangs on the wall?

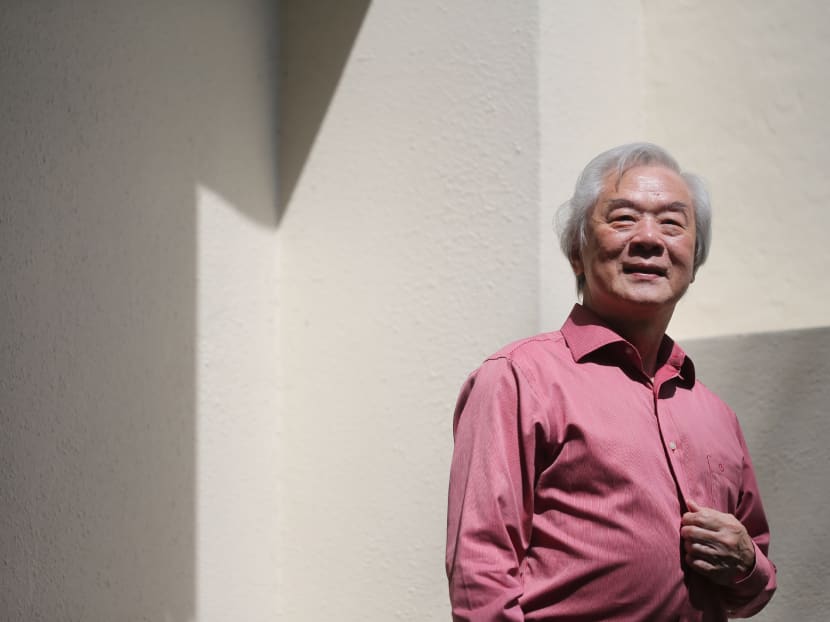

Here, we look at the story behind one of Singapore’s most iconic paintings on display, Chua Mia Tee’s National Language Class.

THE PAINTER IN HIS STUDIO

Even before taking its pride of place inside the museum’s DBS Singapore Gallery, Chua’s 1959 social realist painting of people taking Malay language classes already had a long connection to one of the two historical buildings that comprise the National Gallery. Back in the 1960s, it was hung at the City Hall after S Rajaratnam, then-Minister for Culture, took a liking to it after seeing it at an exhibition.

“So I gave it for free! It was an honour to give it to the minister,” shared the 83-year-old Chua in Mandarin, during a recent chat with him at his home in Bukit Timah.

The recent Cultural Medallion recipient recalled how he had come to create one of his most memorable paintings — National Language Class was his artistic response to Rajaratnam’s call for everyone to study Malay.

By then, Chua had already painted another iconic work, Epic Poem Of Malaya. The powerful piece, done in 1955, featured Chinese Middle School students on a picnic, listening to someone recite an imaginary poem about the future of what was then-Malaya. But if Epic Poem Of Malaya was Chua’s response to the colonial situation of the times, his new work would be about nation-building.

The language issue had resonated well with Chua, who remembered growing up in Geylang surrounded by Malay neighbours and listening to a lot of Malay songs on radio. He also used to speak the language fluently, having taken up language classes.

It took him 20 days to finish the painting in his cramped studio somewhere in Hougang “near a cow farm”. The kampung house he rented was so small there was only space to work on one painting at a time.

Chua also revealed that much of National Language Class was drawn from his imagination and not from photographs (he couldn’t afford cameras back then, he joked). Some figures, though, were based on people he knew: The woman at the rightmost part of the painting was his wife, the painter Lee Boon Ngan (the sister of Chua’s fellow artist Lee Boon Wang). Meanwhile, the cikgu (or teacher) holding court was modelled after an Indonesian friend named Herman Ali.

After its stint at the City Hall, the painting would regularly transit between storage vaults and other shows. It has been given an airing a few times in recent years, such as at an exhibition on art made during the Malayan Emergency at the Singapore Art Museum in 2007 and a survey on modern art at the National Museum of Singapore in 2013. Through the years, it has also inspired other works, directly or otherwise: From an eponymous theatre production by the group spell#7 (who had also done another show on Chua’s Epic Poem Of Malaya), to artist-archivist Koh Nguang How’s exhibition Errata, which had been inspired by an error in the dating of National Language Class in a seminal book on Singapore art (it was erroneously dated 1950, rather than the correct 1959).

Despite all of these, Chua said he had not expected the painting to achieve such an iconic status. In fact, at the time of our interview, he hadn’t seen it for quite some time, except for a recent trip to the Heritage Conservation Centre (HCC) in Jurong to check up on some minor touch-ups done by conservators before it was brought to the National Gallery.

“Someone touched it up, but the brush strokes were a bit different — thankfully, it’s not the important parts,” he quipped.

THE CURATOR IN THE MUSEUM

Suffice it to say, showing National Language Class in the National Gallery was a no-brainer.

The entire exhibition at the DBS Singapore Gallery pivots around one of the elements found in the painting: The show’s title, Siapa Nama Kamu? (Malay for “what is your name?”), was taken from a question written on the blackboard in the painting.

It was an obvious choice for an exhibition that sought to look at Singapore’s history and identity through its art, and reflect a nation and its artists in the midst of trying to understand themselves, said senior curator Shabbir Hussain Mustafa, who heads a team of five in charge of the Singapore side (there’s another team handling the South-east Asia side).

Describing the painting as “one of the critical moments” of Singapore’s art history, he said it was one of the first works brought in from HCC, a process that began last September.

The painting was just one of many works that the museum’s curatorial team had to deal with. From a “working list”, and with lots of research and discussions taking place, it had been a “long and arduous process” of selection. The museum also had to go work with the HCC’s different departments, which handled works in different mediums. The curators’ tasks would range from figuring out the right frames for the art works, waiting for the works “acclimatise” to the museum’s environment after it had been delivered, and figuring out how and where to place the many works in the two permanent galleries.

It was clear from the start, however, where National Language Class was to be hung: At the entrance of one of the DBS Singapore Gallery’s rooms on social realist and modernist works. It had to be the first thing visitors would see.

“All the (rooms) are anchored by key works at the start and at the end, so the location and site (for National Language Class) was quite clear from the start,” said Mustafa. “It’s a work that can command a space.”

They also put one artwork at an angle in front of it — a sculpture by Chua’s brother-in-law Lee Boon Wang titled Before The Moment Of Painting. It was of Chua himself, seemingly pondering his next artistic move.

“The idea was we wanted the public to look at National Language Class in relation to it,” said Mustafa.

The painting is, of course, just one of the many works that will collectively tell the museum’s story of Singapore art. And coupled with the other regional works, Mustafa considers the museum “an immense opportunity … to tell our own histories on our own terms”.

THE MUSEUM GUIDE AND HER AUDIENCE

While the curators were busy getting the art works up, others were equally busy getting the word out.

Months before the opening, the museum has already gone on a full-scale publicity campaign. It was a wide-ranging one that even tapped heavily into popular culture and celebrities, including a Channel NewsAsia docudrama on pioneering artist Georgette Chen, which starred actress Rui En; a graphic novel on Chen by artist Sonny Liew; and an outreach programme called Portraits Of The People endorsed by another celebrity, Joanne Peh.

The most sustained initiative was its My Masterpiece series on YouTube, which saw entertainment and lifestyle personalities such as JJ Lin, Suhaimi Yusof, Kumar, Anthony Chen and Peh talking about their favourite artworks in the national collection. For National Language Class, it was Cultural Medallion recipient Edwin Thumboo who waxed poetic about Chua’s painting.

After the museum opens to the public, another group of people will step in to become the bridge between the art and the people: The museum docents or guides.

One of these is Elaine Cheong. The 60-something president of the Friends Of The Museum has been playing guide since 1999, whether it’s at the Asian Civilisations Museum, National Museum or Gillman Barracks.

The guides take it very seriously — as trainees, they had to prepare (and test) two one-hour tours, one for each of the permanent galleries, which will include six to 10 artworks. After signing up in December of last year, Cheong and the other trainees had to attend art lectures every Saturday until July.

Naturally, National Language Class is part of her tour that talks about the theme of Home. Cheong cited how the painting reflected the mood of that time, and the idea of people wanting to make Singapore their home, which included embracing the Malay language.

And like Chua’s own personal experiences that led to the painting, she also felt a personal connection to the work — she had taken Malay as a second language during her secondary school years.

“National Language Class is enduring. Our national anthem is still in Malay. It speaks of Singapore being part of this region,” she said.

Beyond the big picture, though, it’s also Cheong’s task to get museum visitors interested in the painting as a painting.

She plans to talk about the colours Chua used, the different elements such as the blackboard and the table (“Who uses such things these days?” she quipped), and the teacher-student relationship back in the day. During our chat, she also pointed out a detail in the painting we had not noticed before: One of the characters had a mourning cloth pinned on his left sleeve.

Being exposed to art has changed the way she looks at things, and Cheong hopes to pass this on to the museum’s visitors. One of the best rewards of being a museum guide, she said, is when people are inspired enough to visit and check out the works again.

And in that sense, the experience of seeing a work such as National Language Class comes full circle — from something that stems from an artist’s mind to something that grows in the public’s imagination.

The National Gallery Singapore’s two-week opening celebrations begins on Wednesday. Complimentary tickets from http://tickets.nationalgallery.sg. Opening hours are from 10am to 7pm (Mon to Thur) and 10am to 11pm (Fri, Sat and Sun). The outdoor weekend art carnival from Nov 27 to 29 will be open from 5pm till midnight.