Singapore’s Second Gen artistic adventures

SINGAPORE — With Singapore’s visual art scene hurtling forward at breakneck speed, buoyed by many art fairs, aggressive galleries and new art centres, the preoccupation with contemporary art and its youthful practitioners nowadays is undeniable and, perhaps, understandable.

SINGAPORE — With Singapore’s visual art scene hurtling forward at breakneck speed, buoyed by many art fairs, aggressive galleries and new art centres, the preoccupation with contemporary art and its youthful practitioners nowadays is undeniable and, perhaps, understandable.

But two ongoing exhibitions at the Nanyang Academy Of Fine Arts (NAFA) make the case for the scene’s pioneers. It is in many ways a call for a breather to look back and take stock.

Both Ho Ho Ying — Present and Joie De Vivre: Chen Cheng Mei present a spread of works covering more than half a century of practice by two members of Singapore’s so-called Second Generation, or those who have been taught or mentored by First Generation icons like Lim Hak Tai, Cheong Soo Pieng, Liu Kang and Chen Wen Hsi. With works spanning from the ’50s to the 2000s, Ho and Chen would have very likely been influenced by the Nanyang Style and the adventurous East-meets-West ethos that informed it.

There’s much to learn from both artists, said Bridget Tracy Tan, Director of the Institute Of South-east Asian Arts and Art Galleries at NAFA.

“We may allude to specific canonical fixtures and styles to discuss how their art looks, but to respect and truly understand their style is to look at their work always with fresh eyes,” she said.

CREATIVE ABSTRACTION

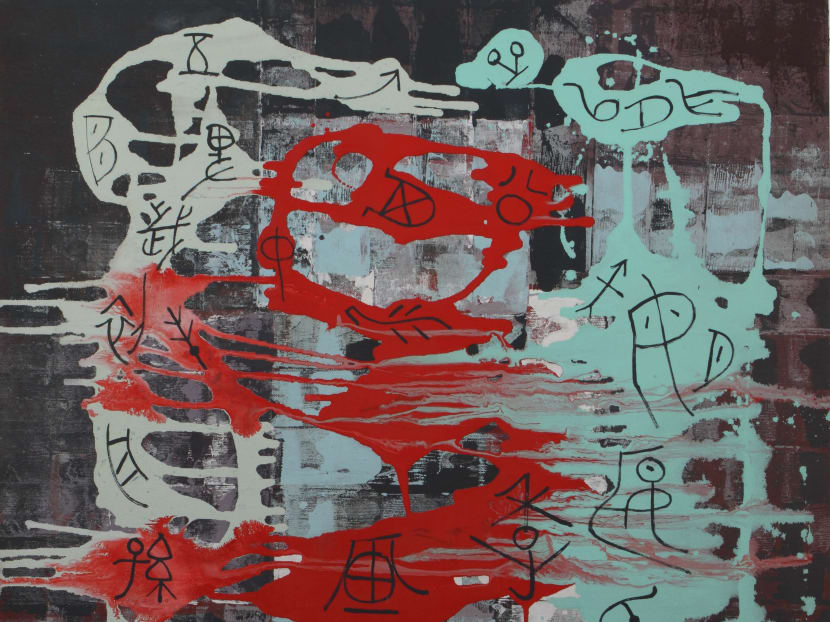

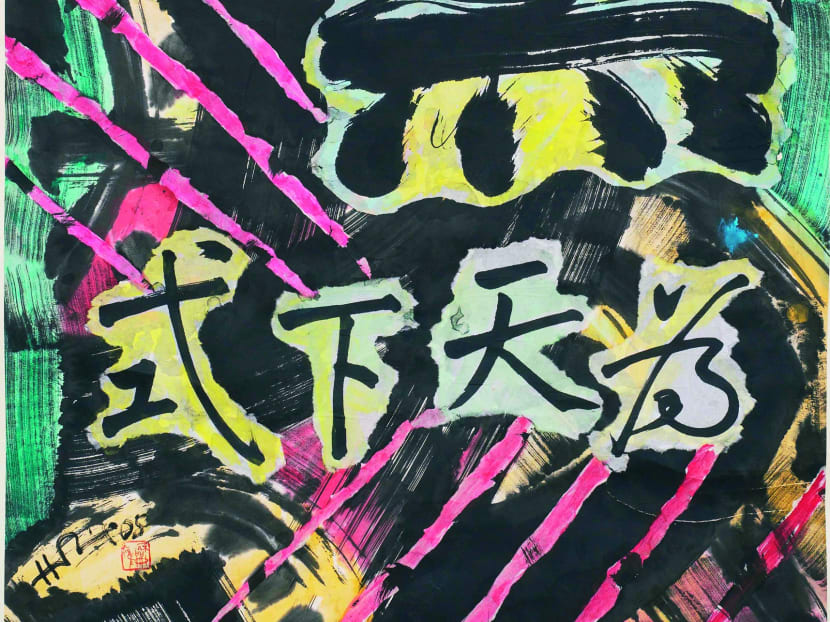

That’s certainly the case in Ho Ho Ying — Present. The 78-year-old artist-art critic and 2012 Cultural Medallion recipient’s 80 pieces are primarily comprised of his trademark abstract expressionist and experimental calligraphy pieces done from the ’50s to 2011.

While a name like Pollock might be thrown into a discussion of his abstract works, Ho remarked his work is “not so violent as Pollock’s. I’ve got some order.” There’s a gentle quality to his paintings, not least because of his strategy of pouring paint and meticulously dribbling, instead of drawing, lines in some.

Elsewhere, Ho’s exploratory nature would see him use spray paint in a work like Outer Space And Black Hole “to make it more interesting” and others recall graffiti-like strategies. (He would good-naturedly quip about how loan sharks — by splattering or spraying paint on walls — stole his “tactics”.)

His inventiveness becomes more evident in his use of calligraphy. An abstract piece like Fossils is infused with Chinese calligraphy and ancient Chinese ideograms. And in the ’90s, he turned the traditional world of calligraphy upside down, literally. Calling them “creative calligraphy”, Ho combined both the rules of Western painting and Eastern calligraphy as characters could be read from the bottom up, from the centre outwards, or even partially obscured. He would make collages of various calligraphy pieces. “I would rearrange them, break them up, join together, until it becomes something new,” he shared.

Ho’s seeming appetite for artistic innovation would, on the surface, be contradictory to one seminal incident in Singapore’s art history that the artist was linked with. In 1972, conceptual artist Cheo Chai Hiang claimed that his piece, 5’ x 5’ (Singapore River), was rejected by the Modern Art Society, then headed by Ho. It was essentially a list of instructions to create a blank square piece — a completely out-of-the-box idea at that time — and Ho reportedly wrote the rejection letter.

Ho has since insisted it was not a rejection but a differing view. “We weren’t against it. It didn’t mean the society didn’t approve it,” he said. Of that pivotal moment of the art scene, the incident wasn’t a case of breaking away, he said, but a “continuation” of debates regarding art. Indeed, the former art critic clarified that he is not against contemporary art. “We’re all on the same train and different thinking (is good), not to fight but to debate and go deeper,” said Ho. And judging from his works in the exhibition, this senior artist is still very well in the here and now.

TRAVEL TIME

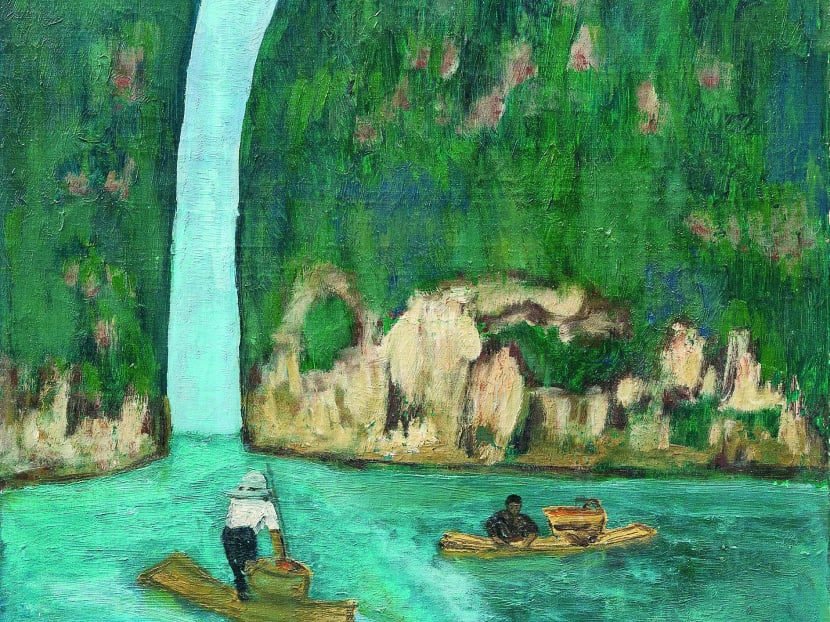

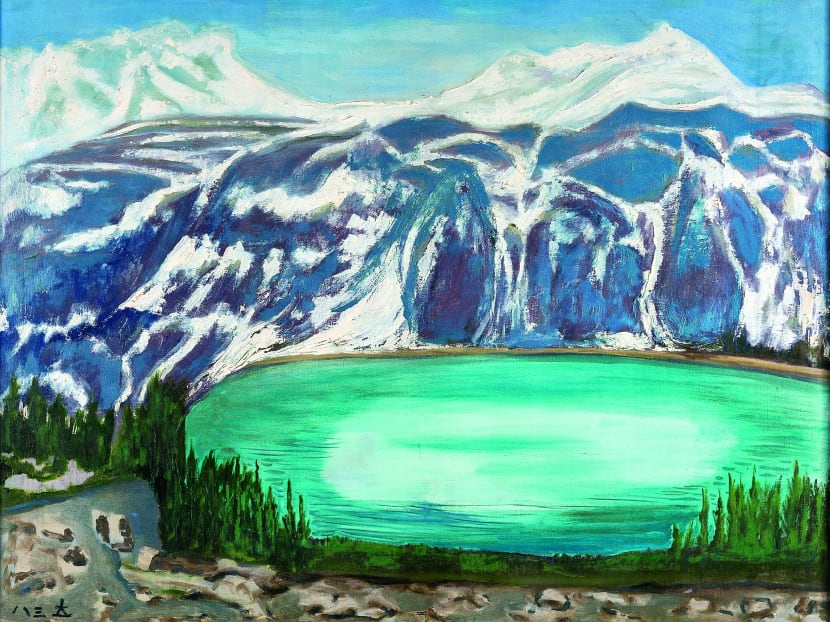

If Ho embodied the supposed spirit of evolution and continuous reinvention of the Nanyang Style in his abstract and “creative calligraphy” works, his contemporary Chen Cheng Mei personifies another aspect of the Nanyang ideal: That of exploring art through travel and of portraying subject matter akin to that historical trip to Bali by Singapore artists in 1972.

The 40 paintings and sketches in 86-year-old Chen’s solo Joie De Vivre highlight the places she went to. Done between 1954 and 2005, and mostly in strikingly vivid colour, the exhibition is a veritable album of landscapes and portraits of people from around the world.

Drawn to exotic cultures and scenery, it would seem on the surface that there’s very little in terms of stylistic change for Chen — her “naive” approach, the extensive use of colours that sometimes echo those of post-Impressionists Gauguin and Cezanne to capture the essence of a place. Indeed, it’s the landscapes and topography rather than the portraits of people that grip this writer. Those on huge canvasses in particular overwhelm us with their vastness of space and vividness of colour.

But her travels did not simply echo that well-known Bali excursion by the Singapore artist. Chen was already a regular traveller as a member of the Ten Man Art Group, a coterie of artists who ventured around the region throughout the ’60s. As a female artist, she was also a rarity.

“When she travelled with the Ten Men Art Group, there were a handful of female artists present (but) none have noteworthy careers,” said Tan. There were other female artists making their mark like Georgette Chen, she added, but many juggled between being artist and teacher.

“Perhaps Chen Cheng Mei’s significant departure from this is that she embraced art-making full time and spent many years travelling abroad with colleagues and family. All these travels yielded the bulk of her artworks,” said Tan.

Taken side-by-side, Ho and Chen’s respective solo shows reveal the ways in which they artistically differ (even if their paths have occasionally crossed, such as for an exhibition in Monaco in 1981, where Ho invited Chen) but you could likewise see a common sensibility in their pursuit of art.

Said Tan: “Painting as a genre is difficult because there are paradigms against which you can make comparisons, in both Chinese and Western traditions. But to seek out your own style and your own way, regardless, is hard work. Ho Ho Ying and Chen Cheng Mei exemplify what it means to live and embrace life as an artist without thinking about global trends, fashion and commerce.”

Ho Ho Ying — Present runs until March 30 and Joie De Vivre: Chen Cheng Mei runs until March 23, 11am to 7pm, at NAFA Campus 1’s galleries. Free admission. Closed on Mondays.