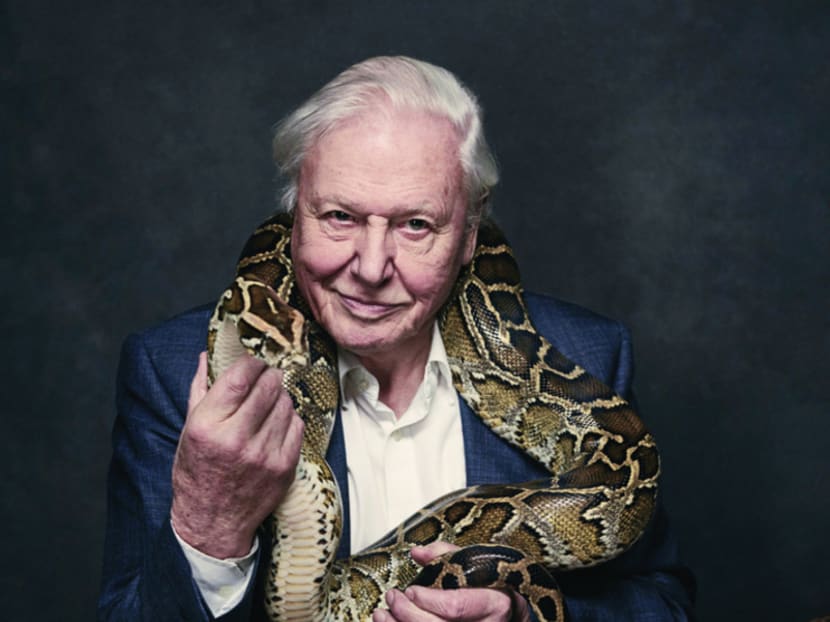

Why David Attenborough, at 90, is the sexiest man on earth

LIVERPOOL – So much has been said about the venerable Sir David Attenborough — about his life’s dedication to the study of the natural world, his boundless spirit and his incalculable legacy to conservationism — that there is nothing we could say that has not been said.

LIVERPOOL – So much has been said about the venerable Sir David Attenborough — about his life’s dedication to the study of the natural world, his boundless spirit and his incalculable legacy to conservationism — that there is nothing we could say that has not been said.

Therefore, as the only television personality to have made shows in black and white, colour, HD and 3D prepares to celebrate his 90th birthday this Sunday, we would simply like to campaign for his being named the world’s sexiest man.

Trust us when we tell you that when we attended the BBC Worldwide Showcase event in Liverpool in March together with Attenborough, his presence elicited a bigger flurry than that for global celebrities such as David Beckham and Matt Le Blanc.

When we sat down to a round-table interview with him, the excitement was palpable. Hard-boiled journalists who had been laissez-faire in interviews with other stars just minutes before, were suddenly jostling to get their questions in. Everyone somehow felt compelled to preface all their sentences with a reverential “Sir David”. And middle-aged male journalists were the first to crowd around him after the interview, asking for selfies and autographs like besotted Japanese fangirls.

It all goes to show that, in spite of today’s shallow celebrity culture, a well-developed cerebral cortex and the ability to narrate mellifluously will always put a man at an evolutionary advantage.

Lest you think we’re being flippant or disrespectful when we say Attenborough, who was knighted in 1985, is the sexiest man alive, well, he himself would probably agree, judging by his answer to one journalist’s uninspired question, “If you were an animal, what animal would you be?”

“There is a thing called the Algerian jird,” he said, straight-faced but with a twinkle in his eye, “which has the highest pelvic thrust rate of any copulating animal.” He then shrugged slightly as if to say, ‘Nuff said.’

As you can tell, one can always count on Sir David to address any question most succinctly and effectively. Here, in his own words, are the wit and wisdom of the world’s most alluring nonagenarian.

Q: You’re 90 this year. What’s your secret to ageing well?

A: Luck. No, it’s true. I’ve got two brothers. Both of them are dead. And I’m not more virtuous than them. It’s just luck. But it also seems to me that if you are lucky, you are very ungrateful not to take advantage of it or recognise it.

Q: What do your fans most commonly say to you?

A: Well, what children always say to me, always, is, ‘What is your favourite animal?’ (The answer) depends (on) how I’m feeling. But if someone serious asked me what my favourite animal was, I’d have to say an 18-month-old human baby. Because actually, that is the most extraordinary organism that evolution has produced. And the mothers and fathers among you will know that’s true. Every day it’s a new creature; it learns new things. So, nothing can compare with a human baby. Otherwise, I’d say, the weedy sea dragon.

Q: Do you have a least favourite animal?

A: Yes. I don’t like rats. Because rats have run over me, walked over my face when I’ve been asleep in the Solomon Islands, and come up between my legs when I’ve been on the loo in India.

Q: What is the craziest place that you have been to during your travels?

A: The craziest place is the South Pole. It’s crazy because it is just a sheet of ice. There’s nothing to be seen. There’s not a plant, nothing. And yet human beings, in my father’s lifetime, died to get to that place. The embarrassment about that is that you really have to hope the director is your friend if you’re supposed to be talking to the camera and there’s a bear coming. They say: ‘What about polar bears? Very dangerous. Can you run faster than a polar bear?’ The answer is: ‘No. I don’t have to run faster than a polar bear. I just have to run faster than the sound recordist.’

Q: Have you ever been attacked by an animal?

A: Not seriously, because I’m too much of a coward.

Q: You don’t like being called a national treasure. Why does it make you uncomfortable?

A: Because ‘national treasure’ isn’t a vote. A national treasure is a way in which a journalist, when he’s got no real story to tell, dreams up something in order to tell a story. Nobody’s voted for it. It doesn’t mean anything. You don’t get double your money or even 10 per cent more money.

To be absolutely truthful, I’m in a very fortunate position. I get the credit because my voice is on it. I don’t make these films. If you look at the credits, there are 50 cameramen who made this thing. If ever there was a team effort, it’s making natural history films.

Q: How do you feel about your own voice, which has taken on a life of its own?

A: By and large, my ideal commentary is the one that doesn’t exist at all. The ideal film is the one in which the human voice intrudes the least. And I think there are some very simple rules as a narrator that you should observe, as with writing a commentary: You shouldn’t use two words if you can use one, and you shouldn’t go into very flowery language, with very complicated adjectives, because viewers can see. If you say this is a really wonderful deep soul-moving moment and they can actually see it, they don’t need you to tell them; and if they can’t see it, they think you’re putting it on.

Q: How would you like to be remembered?

A: I know this will sound terrible — corny, really — but I don’t wish to be remembered particularly. I really mean it. But I would like to think that I helped the BBC to produce a truthful image of the natural world as it was, to the best of our ability. We introduced people to animals they never dreamed of, and more importantly still, to concepts they had never dreamed of. It had never occurred, even to naturalists, 50 years ago, that we could possibly destroy the environment. There were cities in this country, 60 to 70 years ago, that poured raw sewage into the sea on the grounds that the sea was infinitely big and it would just wash it away. Unthinkable now. How attitudes to the natural world have changed. People will talk to you and say: ‘The giant lemur in Madagascar — wasn’t that fantastic.’ I filmed the first film that had ever been made of that creature. And now, taxi drivers in New York will talk to you about it. It’s a paradox that the human race is more divided from the natural world than it has ever been, and yet knows more about it. And if that is true, television has been responsible for doing that.