The fragile and the timeless

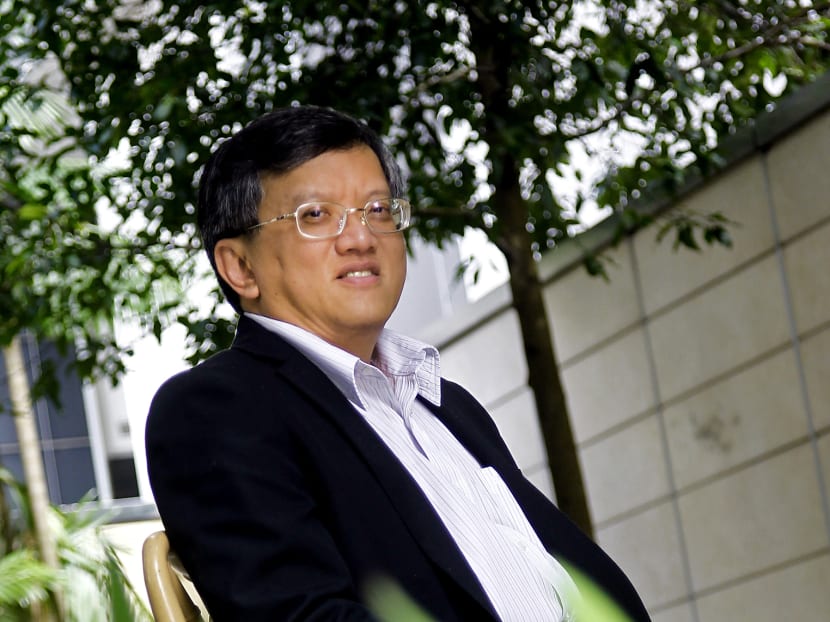

He is intimately acquainted with architectural icons built to stand the test of time, such as the Gardens by the Bay, the Supreme Court and other recognisable structures in Singapore. But what sets architect Khew Sin Khoon’s heart aflutter is a creature that embodies the fragile and ephemeral.

He is intimately acquainted with architectural icons built to stand the test of time, such as the Gardens by the Bay, the Supreme Court and other recognisable structures in Singapore. But what sets architect Khew Sin Khoon’s heart aflutter is a creature that embodies the fragile and ephemeral.

He is one of Singapore’s foremost butterfly experts, having fallen in love with the flying jewels of the insect world 40 years ago while growing up in Malaysia.

On a typical weekend, Mr Khew can be spotted at a reservoir or in Pulau Ubin or Semakau with other enthusiasts, scouting for places where butterflies are likely to feed or probe the ground for water and nutrients. These photography buffs might soak in a stream or lie on muddy ground to snag a prized shot, and Mr Khew’s friends have joked that he looks nothing like a corporate boss in his white shirts made for the outdoors.

The easy-going, self-effacing 54-year-old is, in fact, President and Chief Executive of CPG Corporation. The architectural, project and facilities management firm, which also provides engineering consultancy services, recently celebrated its 180th anniversary. Its body of work includes Changi Airport’s Terminals 1, 2 and 3, the National Museum of Singapore and the upcoming National Art Gallery.

CPG began as the Public Works and Convicts Department in 1833, became the Public Works Department (PWD) in 1946, was corporatised in 1999 when acquired by Temasek Holdings and became CPG Corporation in 2002. Last year, it changed hands from Australian company Downer EDI Group to China Architecture Design and Research Group.

‘JAILED’ ON THE JOB

Mr Khew has been watching the company develop — from handling local public infrastructure projects to forays into markets such as Pakistan and Ethiopia — since 1984 when he joined fresh out of the National University of Singapore.

Born in Penang, he came to Singapore on a government scholarship and was to be posted to either the PWD or the Ministry of Defence to serve his eight-year bond.

At the interview, he “quite innocently” wondered if Malaysians could serve in the Defence Ministry. This gave the interview panel pause for thought and he was promptly posted to the PWD, Mr Khew recounts with a chuckle, one of many anecdotes shared over lunch at The St Regis Singapore.

The mid-1980s were busy nation-building years and the young man was “pretty consumed with work”, handling schools in his early days. He once handled four schools simultaneously and was later involved in the development of Woodlands Polyclinic and Tanah Merah Prison.

“About 10 years of my life was spent working on Tanah Merah Prison,” Mr Khew says. It was a project “some of the boutique architects would turn up their nose at. I mean, how can a prison win you any awards?” But he saw another side to it: A chance to contribute to society.

It was an “extremely challenging” project for a young architect. Instead of modelling it after Changi Prison, which was poorly ventilated with very small windows, the team took a humanistic approach and studied how to ventilate the cells using design.

Mr Khew locked himself up in a cell for a few hours to feel first-hand the morning temperatures and movement of the sun, and spoke to wardens and prisoners to understand users of the future facility better. The cells were designed with lower windows that did not compromise security, he said.

The team also studied prisons in the United States. “The Singapore prison system is very, I would say, mature. We believe in rehabilitation, not only incarceration,” he notes.

A FLYING-SAUCER START

The slate of social infrastructure projects prompted Mr Khew to sink roots and become a citizen. “The 1980s were very ‘nation-building’ years. Being part of it made me proud to be a part of Singapore’s history … I decided this is home.”

More projects followed, including the Supreme Court — a partnership with Foster + Partners that evoked strong reactions from the public and fellow architects. Complete with a “flying saucer” on top, it is a design “you either like or don’t like”. “I guess the form is very subjective, but functionally, it works well as a space,” says Mr Khew. For starters, it is a lot simpler finding one’s way around the building than its predecessor.

That it is commonly known as British architect Norman Foster’s design is fine with Mr Khew. “We were just the elves that went around picking up all the pieces for the ‘starchitects’. But along the way, we tried to learn detailing from him, the process of architectural design, how they presented to people, how they convinced clients and their very sustainable practice,” he says. “Every encounter with a foreign architect, there’s always something to learn from them.”

Foster + Partners’ emphasis on sustainability led to features such as a weather mitigation facade for the Supreme Court, which was completed in 2005. For instance, harsh sunlight never pierces the viewing gallery on its eighth floor — shaded by dint of it being the bottom half of the “flying saucer”. The experience with Foster + Partners started Mr Khew on the journey of sustainability and consciousness of the environment in his work.

CHEK JAWA

This, the firm rigorously practised for the redevelopment of Chek Jawa. They started pondering how a boardwalk could be constructed “without touching the ground” even before the nature groups came knocking.

Instead of trucking in equipment from inland, CPG did piling from the sea, using a piling rig mounted on a flat-bottomed barge that only came in during high tide. This avoided damage to the sea floor and, once the first stretch of the boardwalk was constructed, cranes were lifted from the barge to the boardwalk to complete its entire 2.5km length.

The boardwalk’s planks are made of fibreglass-reinforced concrete, whose edges Mr Khew told the contractors to keep jagged to create the feel of a rustic kampung.

By then, his passion for butterflies had reignited after largely laying dormant during his university days and he joined the National Parks Board in the mid-1990s as a volunteer on butterflies. Mr Khew had grown up chasing butterflies with a net, climbing trees and catching fish in drains in Malaysia.

His favourite butterfly, in fact, is one that got away the first time.

Called The Commander, or Moduza procris milonia, he had spent two hours chasing the skittish specimen in Petaling Jaya but did not manage to catch it. “I remember it for life, not because of its beauty but because of the experience!”

WANDERING YOUTH

His father was an engineer with Shell and would move the family when work demanded — from Penang to Johor Baru and Petaling Jaya before returning north — causing the young boy much trauma when he had to part with friends.

“In those days, there was no email and phone calls were very expensive, so the moment I left Johor Baru, I almost cut ties with everybody. A couple of letters here and there as pen pals, and that was it,” he recalls.

Mr Khew reckons he was a bit of a rebel in his younger days even as he pursued diverse interests. His father had encouraged him and his brother to learn a musical instrument, but it seemed unappealing — until his organ teacher, a nightclub musician, taught him pop songs and dispensed with routine keyboard finger exercises.

When he himself taught the organ to others later at a music school, he did the same and would tell students to play what was comfortable and pleasant to their ears.

What stayed constant was his exploration of the outdoors. “We had to find our own entertainment in those days because Dad was always working and Mum was always making sure the house ran smoothly.”

From catching and killing butterflies, he progressed to learning their taxonomic parts and Latin names, thanks to a supportive science teacher. His father also got a carpenter to make him boxes in which he could pin the butterflies.

BEAUTY AND GRACE

Mr Khew is a pioneer of the ButterflyCircle, a group of enthusiasts and hobbyist photographers, and in 2010 he authored a field guide on butterflies in Singapore (there are about 300 species here, mostly forest-dependent).

In the introduction of the impeccably-structured tome, he wrote that he has “never ceased to be amazed at their beauty and grace”.

ButterflyCircle — which now consists of about 40 regulars — started venturing to Malaysia and Thailand in 2004.

It was in Johor’s Endau Rompin National Park that Mr Khew and his friends got chased by a wild boar. Another time, the group had a close encounter in the middle of the night with a herd of wild elephants that stomped through a banana plantation beside the dormitory. Another reason he loves Endau Rompin: “It has no handphone signal.”

His wife, who is also 54 and works in library IT systems, is not a butterfly enthusiast but joins him on his jaunts for the exercise. Their two sons aged 23 and 24 are more into computer-gaming and cyber security.

NOT JUST PRETTY PLANTS, BUT THE LALLANG TOO

As an architect and butterfly enthusiast, Mr Khew is well aware of the tension between development and nature conservation, and of the different views held by members of the public and nature groups.

He is “against something happening to the Central Catchment Nature Reserve” and is contributing to efforts by nature groups to compile scientifically rigorous reports to address the biodiversity impact of an underground train line cutting through it.

But he also notes: “You have to be practical and take a balanced view of various options. In land-scarce Singapore, we are under a lot of pressure to develop whatever land we have left, to optimise it.”

Architects and landscape architects, he says, can help promote biodiversity in built environments by incorporating nectarine and caterpillar host plants, and by having more organic designs that leave portions of a site to grow wild.

“Don’t bring in pretty plants only. Humans just look at a pretty plant and say, ‘I want this’. But if it’s not a host plant for a caterpillar, there’s no life — without caterpillars, the birds won’t come.”

Native species should also be used, including plants perceived to be weeds, such as lallang and snakeweed, he says.

When it comes to leaving portions to grow wild, Mr Khew says more awareness of the ecosystem among officials and the public is needed.

Education of urban planners and civil servants is key, as they serve as ambassadors to tell the public that in order to have beautiful butterflies, plant-munching caterpillars are part of the deal. Less popular creatures such as snakes and mosquitoes are also part of the ecosystem.

His favourite area in Gardens by the Bay — a CPG partnership with Grant Associates and WilkinsonEyre Architects — is an area 10ha to 12ha in size beyond The Meadow that has been left wild.

There are 50 butterfly species there, as well as kingfishers and lizards, he said. “It’s a very different environment from what is inside the domes and most people don’t know (about it).”

TAKING S’PORE’S LESSONS ABROAD

Mr Khew has also tried to grow appreciation of nature within his firm.

This year, he began inviting experts to share with CPG’s architects, engineers and planners on spiders, urban landscape ecology and other topics relevant to their work in “creating biodiversity-friendly environments in our projects”. The talks take place once every two months at CPG’s lounge, with 30 to 50 staff attending.

He sees doing business in countries from China to Colombia as a way of imparting lessons Singapore has learnt from its development. CPG ventured overseas out of necessity after corporatising, but it is also an opportunity to help realise the aspirations of overseas clients to become a quality city, he says.

And if emerging cities can learn from Singapore’s experience to, perhaps, allocate space for cycling tracks even as more room is made for motor vehicles, all the better. CPG has offices in China, Dubai, India, Macau, the Philippines and Vietnam, and 2,164 staff of 28 nationalities.

Asked how he manages such a diverse workforce, Mr Khew says he takes the different personalities and the more vocal members of the team in his stride (“You have to come to terms with it when dealing with the younger generation’s views, and also because it’s a global market”) and draws on his childhood days to “expect the unexpected”.

And on weekends, he heads outdoors. “Butterfly watching is my weekend stress-relief therapy,” he says. “I like to be out in green areas because nature energises me.”