Peng Chang-kuei, chef behind General Tso’s chicken, dies at 98

NEW YORK — Peng Chang-kuei, the Taiwanese chef who invented General Tso’s chicken, a dish nearly universal in Chinese restaurants in the United States, died on Wednesday (Nov 30) in Taipei. He was 98.

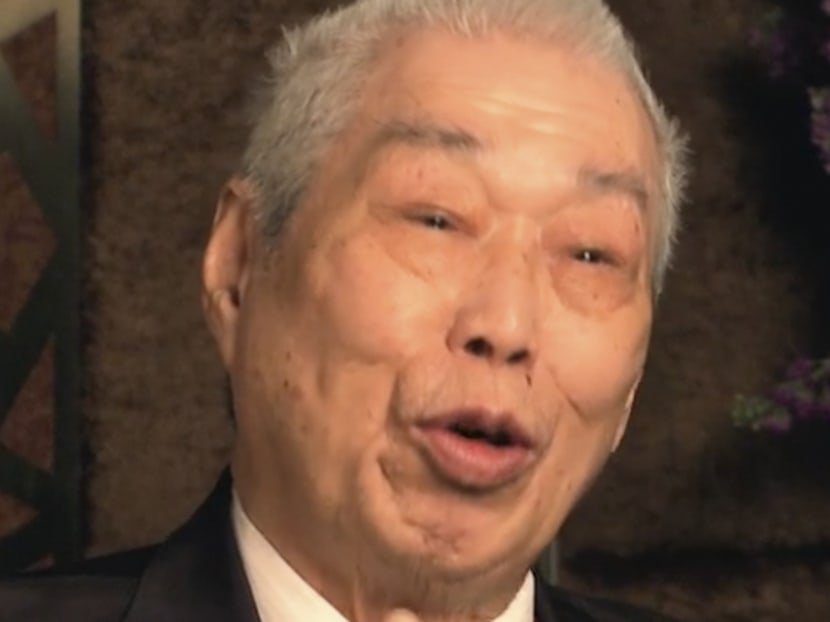

An undated image of Peng Chang-kuei in the documentary The Search for General Tso. Peng, a Taiwanese chef who in 1955 invented General Tso’s Chicken — a dish now familiar around the globe — and later helped popularise it in New York City, died on Nov 30, 2016 in Taipei. He was 98. Photo: Wicked Delicate Films via The New York Times

NEW YORK — Peng Chang-kuei, the Taiwanese chef who invented General Tso’s chicken, a dish nearly universal in Chinese restaurants in the United States, died on Wednesday (Nov 30) in Taipei. He was 98.

The death was reported by The Associated Press.

The British food scholar Fuchsia Dunlop has called General Tso’s chicken (lightly battered pieces of dark chicken fried in a chili-accented sweet-and-sour sauce) “the most famous Hunanese dish in the world.”

But like many Chinese dishes that have found favour with Americans, General Tso’s chicken was unknown in China until recently. Nor was it, in the version known to most Americans, Hunanese, a cuisine defined by salty, hot and sour flavors.

Peng, an official chef for the Nationalist government, which fled to Taiwan after the 1949 revolution in China, said he created the dish during a four-day visit by admiral Arthur Radford, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, during the Taiwan Strait crisis of 1955. On the spur of the moment, he assigned it the name of a Hunanese general, Zuo Zongtang, who had helped put down a series of rebellions in the 19th century.

“Originally the flavours of the dish were typically Hunanese — heavy, sour, hot and salty,” Peng told Dunlop, the author of Revolutionary Chinese Cookbook (2007), which is devoted to the cuisine of Hunan. “The original General Tso’s chicken was Hunanese in taste and made without sugar.”

The dish made its way to New York in the early 1970s after Chinese chefs in New York, preparing to open the city’s first Hunanese restaurants — Uncle Tai’s Hunan Yuan and Hunam — visited a restaurant Peng had opened in Taipei. They adapted the recipe to suit American tastes.

“We didn’t want to copy chef Peng exactly,” Ed Schoenfeld, an assistant to the restaurant’s owner, David Keh, told the website Salon in 2010. “We added our own spin to dishes. And so our General Tso’s chicken was cut differently, into small dice, and we served it with water chestnuts, black mushrooms, hoisin sauce and vinegar.” The chef was Wen Dah Tai.

At Hunam, the chef Tsung Ting Wang — who was also a partner with Michael Tong in another prominent Chinese restaurant in Manhattan, Shun Lee Palace — put a Sichuan spin on the dish. He crisped up the batter and sweetened the sauce, producing a taste combination that millions of Americans came to love. He called it General Ching’s chicken. But as the dish traveled, the General Tso name adhered.

Both restaurants were awarded four stars, the highest rating, by Raymond Sokolov, the restaurant critic of The New York Times.

In 1973, with Hunan fever raging, Peng came to New York and, with Keh, opened Uncle Peng’s Hunan Yuan on East 44th Street, near the United Nations. Peng discovered, to his consternation, that his creation had preceded him, and that the child was almost unrecognisable.

“New Yorkers didn’t realise he was the real thing, and some treated him like he was copying,” Schoenfeld said.

The tangled history of the dish was explored in 2014 in a documentary, The Search for General Tso, directed by Ian Cheney.

Peng Chang-kuei was born in Changsha, the capital of Hunan province, in 1918. His family was poor.

At 13, after running away from home, he began serving an apprenticeship under the celebrated Hunanese chef Cao Jing-shen. Formerly a family chef to Tan Yan-kai, prime minister of the Nationalist government in the late 1920s, Cao had opened the restaurant Jianleyuan in Changsha.

In the 1930s, after the Japanese invasion, Peng moved to Chunking, the temporary Nationalist capital, where he began to gain renown. After World War II, he was installed as the government’s head banquet chef. He emigrated to Taiwan in 1949, leaving his wife and two sons behind, and continued to cater official functions.

He is survived by a son, Peng Tie-Cheng. Complete information on other survivors was not available.

New York proved to be a fraught experiment, as Peng’s restaurant soon closed. “Doom trailed Uncle Peng”, the food critic Gael Greene wrote in New York magazine in 1973. “The pressures of Manhattan restaurant reality were too much for the brilliant teacher.”

Undaunted, Peng borrowed money from friends and opened Yunnan Yuan on East 52nd Street, near Lexington Avenue, where Henry Kissinger, then the secretary of state, became a faithful customer.

“Kissinger visited us every time he was in New York, and we became great friends,” Peng told Dunlop. “It was he who brought Hunanese food to public notice.”

General Tso’s chicken began to assume celebrity status when Bob Lape, a restaurant critic, showed Peng making the dish in a segment for ABC News. The station received some 1,500 requests for the recipe.

Encouraged, Peng reopened his old restaurant as Peng’s, bringing his signature dish with him. Reviewing the restaurant in the The Times in 1977, Mimi Sheraton wrote, “General Tso’s chicken was a stir-fried masterpiece, sizzling hot both in flavour and temperature.”

He left the restaurant in 1981 and opened Peng’s Garden in Yonkers, then returned to Taiwan in the late 80s and opened the first in a chain of Peng Yuan restaurants there. The menu featured General Tso’s chicken. It was listed on the menu in Mandarin as Zuo Zongtang’s farmyard chicken, and in English as chicken la viceroy.

In 1990 he opened a branch of his restaurant in the Great Wall Hotel in Changsha, but it was not a success.

As Hunanese chefs adopted General Tso’s chicken, the dish entered a strange second career. In a sweeping act of historical revisionism, it came to be seen as a traditional Hunan dish. Several Hunanese chefs have described it in their cookbooks as a favorite of the 19th-century general’s.THE NEW YORK TIMES