Diving into Indonesia’s Raja Ampat was worth the 12-hour journey

RAJA AMPAT — We left Singapore at about six in the evening and flew to Jakarta, where we began the first part of our airport junk-food odyssey, with mee soto and doughnuts. A few hours later, we hopped on our next flight to Makassar, which lies further east of Jakarta, and killed another couple of hours in the airport, this time filling our bodies with sugary ice-blended coffee drinks.

RAJA AMPAT — We left Singapore at about six in the evening and flew to Jakarta, where we began the first part of our airport junk-food odyssey, with mee soto and doughnuts. A few hours later, we hopped on our next flight to Makassar, which lies further east of Jakarta, and killed another couple of hours in the airport, this time filling our bodies with sugary ice-blended coffee drinks.

By the time we boarded our next flight and touched down in the port town of Sorong at 6.30am, I was high on sugar, and my eyes felt like peeled grapes, dry and aching from the airplane air.

But in the West Papua region of Indonesia, we eventually found paradise — that is, after we boarded our home for the week, a 32-m “liveaboard” boat for scuba divers, and sailed for another two-plus hours.

Our destination? Raja Ampat, the stunning group of islands featured in ads by the Indonesian tourism board, which wisely leaves out details of the amount of time needed to get there.

But its relative isolation may be a blessing. Raja Ampat, comprising some 1,500 small islands, cays, and shoals ringed by turquoise waters so luminous they beggar belief, has maintained its pristine beauty. This is something of a miracle in South-east Asia, where destruction of marine habitats, even in protected areas, are heartbreakingly common, and fishing continues with flagrant disregard for depleting ocean stocks. Because many of the smaller islands do not have fresh water sources, human inhabitation in Raja Ampat is largely limited to the main islands of Waigeo, Misool, Salawati and Batanta. Resorts and homestays, though growing in number, remain relatively far and few between.

The waters of Raja Ampat — the “Four Kings” — have a reputation for superlative scuba diving, and we were here to find out if this was true.

Creatures feature

The short answer? Yes.

Located in the Coral Triangle which spans the Philippines to Papua New Guinea, the region is famous for its biodiversity. You’re likely to see more species of marine life than you knew existed, some of them endemic to the area, like the Raja epaulette shark — often referred to as a walking shark — which is small, catfish-like in shape with a beautiful brown spotted pattern. Also a common sight are the comic-looking wobbegong sharks — bottom-dwellers with a shaggy beard-like fringe around their mouths, curling tails and a lazy disposition. Sleek, muscular grey reef sharks can be seen circling their prey at the edges of the reef, oblivious to the occasional ripping current, while whitetip reef sharks, their smaller, relatively cute cousins, glide through the reefs leisurely.

Here, marine life thrives. The dazzling schools of fish are at times so dense that the sensation is one of swimming in a kaleidoscope of moving fish — a river of electric blue here, a streak of silvery grey there, a bolt of magenta at the corner of the eye, a shock of lemon-yellow cutting through the crowd. A herd — there is no other word to describe these cow-like creatures — of over 30 humphead parrotfish, about a metre in length, slowly munch their way across a reef (they eat coral, really). In the mornings, if you are lucky, you can watch the majestic trevallies — or to be accurate, several species of these badass, fast-swimming predators — chase down hapless sardines, which school with balletic grace as they swim for their lives.

For those with a fondness for the strange, there are the critters — unusual, often tiny marine creatures — and cephalopods. You might see the delicate and deadly blue-ringed octopus, pretty as a Ming vase, or the iridescent bobtail squid the size of a grain of rice. You might see the boldly-striped wunderpus — not to be confused with its lookalike, ironically named the mimic octopus — and it might be too busy mating to hide from your rude stare. A few species of pygmy seahorses — including the really, really teensy Denise’s pygmy — can be found on massive gorgonian sea fans, assuming your eyes are up to spotting these miniscule, perfectly camouflaged creatures. An orang utan crab might wave one of its tiny red hairy arms at you. There are more reputable dive sites in South-east Asia for such creatures, but Raja Ampat is no slouch in this area, in the hands of the right guide.

And then there are the oceanic manta rays, superstars wherever they go. With wingspans that easily measure 4m or more, these graceful giants sometimes soar over divers, seemingly without fear, while us clumsy human beings try to maintain our buoyancy and stay put for a good view. The danger is running out of air while you are in rapture, unwilling to leave and forgetting to monitor your air gauge.

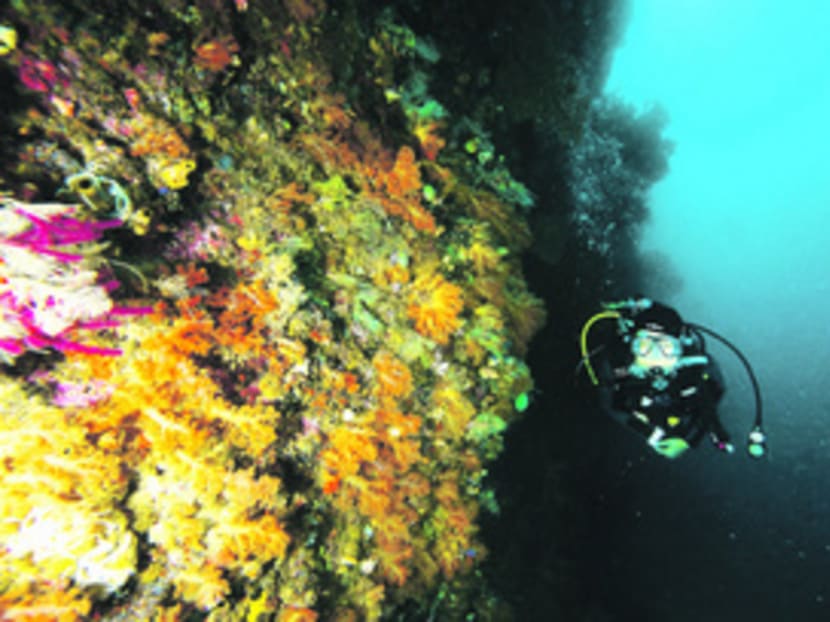

These marine marvels are set amid an extraordinary underwater landscape of ridges and sea mounts invisible from the surface and never-ending reef walls, punctuated by grottoes, canyons, and arches, and covered with colourful hard and soft corals, sponges and sea fans.

The life aquatic

The best way to experience the underwater pleasures of Raja Ampat is to spend at least a week at sea on a liveaboard, sailing from one site to another, guided by the knowledge and instincts of the crew on local weather conditions and currents. Land-based diving is possible in Raja Ampat, but this restricts how far you can go, and there is something to be said for shaking off the shackles of land. On a liveaboard, shoes are packed away for the week, watches are left in rooms, and the passage of time is marked by dives and punctuated by meals: A dive before breakfast, one before lunch, one after lunch and one at nightfall, before dinner.

Between dives, you eat, read, chat with other divers and the crew, and work on your tan, amid a stunning vista of waters in infinite shades of blue, emerald islands both jagged and smoothly domed carved by wind and sea. The wide skies go from pastel at dawn to brilliant blue by day, to orange, pink and purple by dusk, and become strewn with stars at night.

Landfall is occasionally made. The crew takes guests out on rubber dinghies for a tour of a couple of the spectacular lagoons, where you can see the towering cliffs up close, and, when the boat’s motor is turned off, experience a perfect, deep, silence. At the Penemu group of islands — also spelt as Piaynemo — visitors can climb about 300 steps to a small platform to take in those famous views.

When our boat made a stop at an island called Saonek, it was an opportunity to stretch our legs — and also to catch a brief glimpse of village life in West Papua. On an island easily traversed in 15 minutes, there were few shops, and no traffic, although the odd parked motorbike was spotted. Amid simple houses fronted by neatly tended gardens, there was a gleaming mosque and further inland, a church — a reminder of the diversity of Indonesia, even in its remote corners.

Liveaboards are yacht-sized, but in case this conjures images of billionaires clinking glasses of champagne, I should point out that generally, dive liveaboards are rated on how well they cater to the needs of divers — are the guides any good, is there plenty of space for me to gear up and so on — and conventional marks of luxury like bazillion-thread count sheets and plush mattresses are usually not a priority. Not that those seeking the ultimate in luxury travel will lack for options. The famed Aman group, for example, offers a seven-day expedition for an eye-watering five-figure sum.

But what is luxury? For nine days, I was able to immerse myself in one of the most pristine marine environments in the world. Our boat, the Mermaid II, was perfectly comfortable, with every need — dive-related or otherwise — anticipated and cared for. As a diver, you are ultimately responsible for your personal safety, but beyond that, your most pressing decision might be which swimsuit to wear for the day, or whether to skip dessert. The rest of the world went on, but we were suspended in time, in a landscape that hasn’t changed very much since the intrepid explorer Alfred Russel Wallace found his way to Raja Ampat in the 19th century. I didn’t turn over a year’s wages for my holiday, but I felt no less privileged.

The success of a dive trip is very much in the hands of nature. In March, we were lucky to have crystalline visibility for many of our dives, especially around Misool in the south, where the weather was relatively clear. But there were also days of rain and overcast skies and this meant poorer visibility underwater.

But this does not take away from the experience — that is, if you accept that the natural world is not a zoo, and the weather and marine life do not perform like trained animals for your pleasure. Giving yourself over to whatever awaits you is part of the adventure.