The language of survival

Few might have realised the significance at that time, but in making English Singapore’s lingua franca, a decision he made within only a few weeks of separation from Malaysia in 1965, Mr Lee Kuan Yew gave the Republic a fighting chance of overcoming the formidable crises post-Independence.

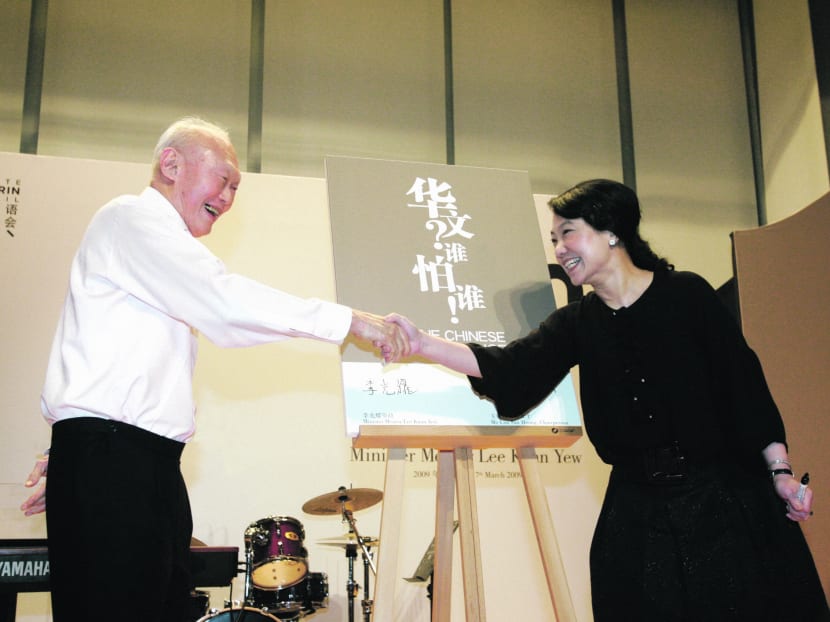

Mr Lee sharing a light moment with Ms Lim Sau Hoong, an award-winning Singaporean designer and businesswoman, at the launch of the 30th anniversary of the Speak Mandarin Campaign at the NTUC Auditorium in 2009. Ms Lim was cited by Mr Lee as someone whose effective bilingualism allowed her to make a contribution to director Zhang Yi-mou’s opening ceremony at the 2008 Beijing Olympics. TODAY FILE PHOTO

Few might have realised the significance at that time, but in making English Singapore’s lingua franca, a decision he made within only a few weeks of separation from Malaysia in 1965, Mr Lee Kuan Yew gave the Republic a fighting chance of overcoming the formidable crises post-Independence.

Adopting the international language of business, diplomacy, and science and technology was about the only way this resource-less tiny island could guarantee its survival after losing its economic hinterland in Malaysia. Unemployment was at 14 per cent and rising.

Mr Lee captured the move’s criticality in his memoirs: “Without it, we would not have many of the world’s multinationals and over 200 of the world’s top banks in Singapore. Nor would our people have taken so readily to computers and the Internet.”

Just as importantly, picking this race-neutral language demonstrated his government’s anti-communalistic stance, helping to keep the peace in a newborn nation made up of a polyglot-settler populace who had struggled for years with racial and religious strife.

“We treat everybody equally. We judge you on your merits. This is a level playing field. We do not discriminate our people on race, language, religion. If you can perform, you get the job,” he said.

This decision was not so intuitive in that post-colonial era as it seems in hindsight. Other newly-independent African countries, Malaysia and India, for example, were throwing out the English language along with the British yoke in a fit of nationalism.

In Singapore too, language was a political issue — except that in its case, English, Malay, Chinese and Tamil were recognised as the four official languages, with Malay the national language and English the main language of commerce and administration.

NANTAH OPPOSITION

But the force with which Mr Lee pursued English language proficiency met with opposition, most robustly from Nanyang University (Nantah) graduates.

They raised the issue of Chinese language and culture in the 1972 and 1976 general elections, after Mr Lee did away with vernacular schools and made Nantah, a source of pride among the Chinese community as it was the only Chinese-language tertiary institution outside China then, switch to teaching in English. The latter move was despite the reservations of many of his colleagues and when it failed, he forced Nantah to merge with Singapore University in 1978.

His most powerful riposte to these opponents: All three of his children were sent to Chinese-medium schools. (From age six, they also had Malay-language tuition at home.)

Mr Lee himself, born to English-speaking parents, had started to pick up Mandarin again only at age 32 and “spent years sweating blood” to master it, a story he recounted in detail in his 2011 book, My Lifelong Challenge: Singapore’s Bilingual Journey.

BILINGUALISM

For the sake of building “a community that feels together”, Mr Lee pushed through the bilingualism policy in 1966. All students had to learn their “mother tongue”, Mandarin, Malay or Tamil, depending on their race, as a second language, and this became a compulsory and critical examination subject in 1969.

“We insisted on the mother tongue because I saw the difference between the Chinese-educated and the English-educated. The English-educated were rootless,” he explained to a team of authors, citing Raffles College students’ indifference although a massive riot was boiling at Chinese High School in 1956, in response to an anti-communist crackdown by the then David Marshall Government.

“If Singapore students all turned out like those in the university hostel, Singapore would fail,” he said.

The nexus between language and culture was crucial to creating a rugged, tightly-knit society with “cultural ballast” because with the language go “the literature, proverbs, folklore, beliefs, value patterns”, he believed.

He later said: “I have no doubts that if we lose ... our sense of being ourselves, not Westerners, we lose our vitality. So that was our first driving force.”

IMPERFECT IMPLEMENTATION

But the various initiatives Mr Lee rolled out in subsequent years to put proficiency in mother tongue on par with that in English were to divide opinions, especially among the Chinese, even up to the present. Indeed, he described bilingualism in 2004 as the “most difficult” policy he had had to implement.

Mr Lee set up Special Assistance Plan schools in 1978 for students who were more proficient in both English and Mandarin to pursue both the subjects as first languages. Critics said the scheme caused ethnic segregation because these schools did not offer other mother tongues.

The following year, he also launched the Speak Mandarin Campaign to eradicate the use of dialects.

While not an insignificant number benefited from the bilingualism policy, particularly after Deng Xiaoping opened up China, many struggled with learning Mandarin. It was partly because many Chinese families retained strong loyalties to the different dialects spoken by their forefathers, but more importantly, it was caused by the way schools were teaching the language.

Mr Lee acknowledged as much during a parliamentary debate in 2004 on changes to Chinese language learning. The imperfect implementation of what he maintains was a sound policy, he said, caused interest in the Chinese language to be killed by the drudgery of rote memorising. He regretted not implementing the modular system earlier.

Reflecting on his belated realisation that language ability was, at best, only loosely linked to intelligence, Mr Lee admitted in 2009 that “successive generations of students paid a heavy price because of my ignorance”.

In November 2011, he started the Lee Kuan Yew Fund for Bilingualism to support ideas that would promote the learning of English and mother tongue. Even towards the end, at his last appearance at the National Day Dinner in his Tanjong Pagar ward shortly before his 90th birthday, he was exhorting parents to give their children an early start in bilingualism.

More in our Special Edition this afternoon (March 23).