Mr Lee Kuan Yew wanted a zoo as successful as Singapore

SINGAPORE — It did not look like an auspicious start. First, Mr Lee Kuan Yew, then the Prime Minister, was worried that the Singapore Zoo’s waste would run into the surrounding reservoir, polluting the water being supplied to households.

SINGAPORE — It did not look like an auspicious start. First, Mr Lee Kuan Yew, then the Prime Minister, was worried that the Singapore Zoo’s waste would run into the surrounding reservoir, polluting the water being supplied to households.

Mr Lee, like other government officials at the time, was worried about the zoo’s animals excreting too much waste, which could be washed into the reservoir, polluting the water. As he said at the zoo’s 20th anniversary dinner in 1993, “I was obsessed with water”.

There were also worries about the amount of food large animals would consume, eating the zoo “out of house and home”, making operations unsustainable.

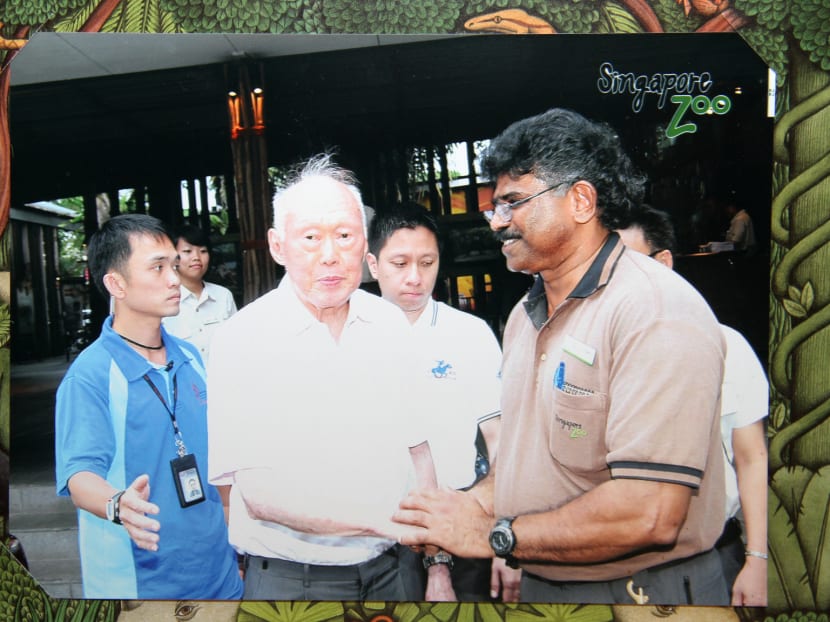

Despite these misgivings, the late Mr Lee went on to become one of the zoo’s most frequent visitors, dropping by almost every year, sometimes with his grandchildren, dispensing advice that shaped the zoo’s development.

For example, to prevent water pollution, the late Dr Ong Swee Lay, who was the zoo’s founder and executive chairman, asked the Public Utilities Board chief water engineer Khong Kit Soon to design a storm-water drainage system that ran along the parameter of the zoo. The drains would channel run-off into the zoo’s own sewage treatment plant. They remain a feature of both the Night Safari and River Safari.

“He only approved it if we had some kind of measure in place to prevent effluent from the zoo from going into the reservoir,” said Mr Vijaya Kumar Pillai, director of zoology at Wildlife Reserves Singapore (WRS), who began working at the Singapore Zoo as a keeper in 1972, a year before it officially opened.

With many zoos around the world operating at a loss, Mr Lee also stressed to the management that the Singapore Zoo needed to be financially viable, while keeping admission fees affordable.

“Dr Ong ... would go play golf with people, ask for sponsorship, adoption schemes (for animals) ... Then the Government came in to give us a grant to help with the operations,” recalled Ms Lok May Kuen, WRS’ director of education.

Mr Lee’s passion for greenery also led him to suggest that the zoo plant more slow-growing, primary forest trees to add to the diversity of the area.

“He has also been very strategic,” said WRS acting chief operating officer Melvin Tan, who started his career at the zoo in 1988 as an assistant curator. “... He suggested slow-growing jungle trees. We could only conclude he was thinking of the future generations.”

Such trees can take 50 years or so to reach maturity. Acting on the suggestion, WRS planted 1,000 trees over three years. “He asked the Commissioner of NParks (National Parks Board) to come and help us, even supply us the necessary trees ... Before that, there was no specific direction,” said Mr Tan, who noted that Mr Lee was knowledgeable about trees and recalled even their Latin names.

His concern for the trees, not just within the zoo but also around Mandai, was such that when six deer escaped from the Night Safari in 2010, Mr Lee was anxious that they be found because they could damage tree bark.

Another animal escape that upset Mr Lee was that of Congo the hippopotamus, which eluded keepers for 52 days in 1974. Mr Lee was concerned about the animal polluting the water, said Mr Pillai.

“He told Dr Ong, ‘You don’t catch it, we’ll close the zoo’. He was so upset,” Mr Pillai added. Ms Lok recalled that during the weeks when the hippo was missing, people here would boil the water from their taps before drinking it.

Mr Lee’s attention to detail knew no bounds. Mr Pillai recalled one of Mr Lee’s visits to the zoo: “I approached and asked if he wanted anyone to take him around. He didn’t ... so the SOs (security officers) just told us, ‘Leave him alone’. And he put his hands on his hips and just walked around, looked at everything. Shook his head a couple of times, and walked back into the car.

“The next thing we knew we got a letter from the P&R (the former Parks and Recreation Department) ... to say that the PM had visited the zoo and found that the trees and your park are poorly maintained ... Dr Ong called a meeting, and the first thing he did was to ask P&R for a few hundred-thousand dollars (for maintenance) and P&R gave him the money,” he said.

Years later, finding Mandai Lake Road was too narrow, Mr Lee saw to it that it was widened. And observing that the columns at the Night Safari building were bare concrete, Mr Lee suggested dressing it up, such as by binding it with rope for a more rustic look.

“He was like a child in that he’s very curious about everything,”Ms Lok said of Mr Lee. “I remember he walked past the gift shop (and asked) ‘Why is this gift shop like this? Go get somebody special to come in and help you run the gift shop’. And then at the next visit, he asked Dr Ong, ‘Has it been done?’. He remembers what he asks you to do.” The zoo later engaged duty-free chain DFS to run its souvenir store, before eventually taking over operations again.

Notably, Mr Lee, who had been concerned about animal waste washing into Upper Seletar Reservoir, also chanced upon a better use for the refuse: Sell them as fertiliser.

“From time to time, he would read some article in the newspaper, and he would tell chairman (about it) ... the Zoo Poo was his idea ... He saw that (a zoo overseas) was doing it, (and) sent the cutting to Dr Ong,” Mr Tan said. The idea was a roaring success and demand was high. However, the operations grew too big to manage and the zoo stopped the practice.

Mr Lee’s suggestions were adopted time and again because they were often sound. “It’s not like we followed them blindly ... They made sense,” noted Ms Lok.

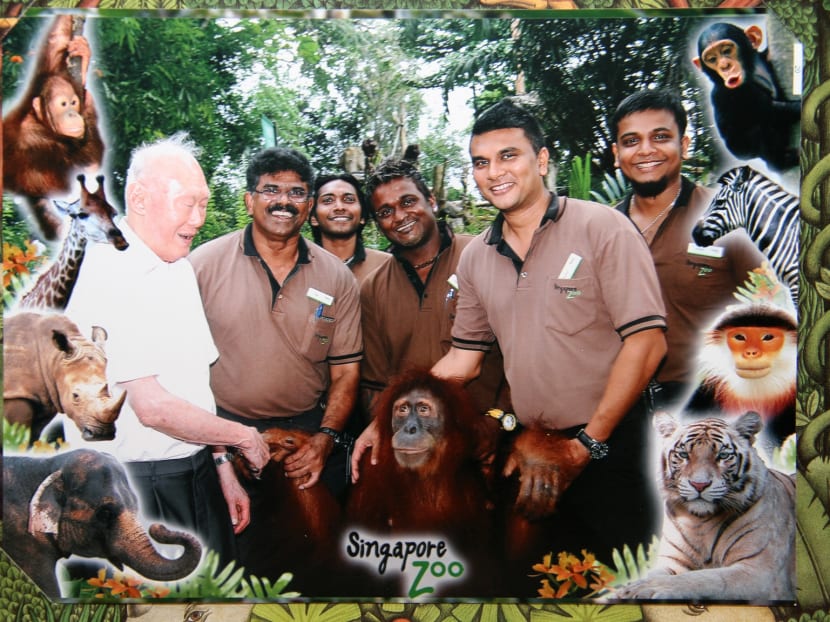

Singapore Zoo zoology specialist Alagappasamy Chellaiyah said he would spend days preparing for Mr Lee’s visit, bracing himself for his questions.

“It used to stress me out, but by 2011, when he visited, I was more relaxed,” he said. Whether he was fussing over whether the animals in captivity could end up inbreeding, or noting the size of the trams being used to ferry visitors around, Mr Lee was ultimately driven by the desire that the zoo, like Singapore, did well. His pride in how the zoo became a world-class facility was evident, and in his speech at the zoo’s 20th anniversary dinner, he credited Dr Ong’s hard work for its success.

Said Mr Pillai: “Once, at the entrance, he saw the number of visitors, he nodded his head. He just nodded he head. He must have felt very happy by the number of people patronising the zoo.”

Even after decades of visiting the zoo, Mr Lee never tired of learning more. Before the River Safari officially opened in 2012, Mr Lee had a chance to meet the resident pandas, and spent 30 minutes grilling their handlers.

And in 2011, after asking if the zoo had found a successor to the late Ah Meng, the orangutan which became synonymous with the zoo,

Mr Lee was introduced to Chomel, Ah Meng’s granddaughter. He shook hands with her.

“You could see the happiness in his face. All my three outings with him, I had never seen him so happy,” said Mr Alagappasamy.