Preserving S’pore’s security via ASEAN

Four decades ago, Indonesia, together with Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand and Singapore, established the Association of South-east Asian Nations, or ASEAN, at a time when the region was in turbulence.

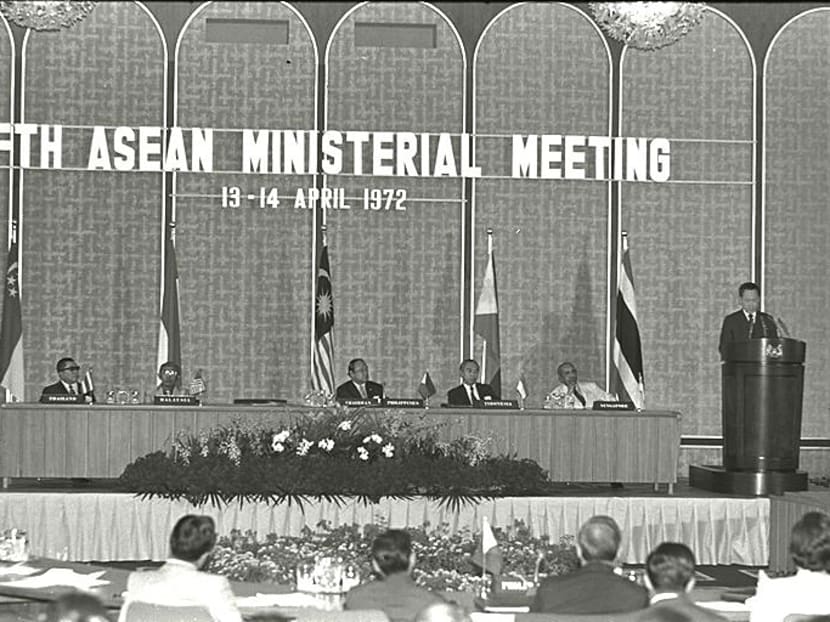

Mr Lee Kuan Yew speaking at the opening of the Fifth ASEAN Ministerial Meeting at Shangri-La Hotel in 1972, when he was Prime Minister. PHOTO: MINISTRY OF INFORMATION AND THE ARTS COLLECTION, COURTESY OF NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF SINGAPORE

Four decades ago, Indonesia, together with Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand and Singapore, established the Association of South-east Asian Nations, or ASEAN, at a time when the region was in turbulence.

It was August 1967: The Cold War was at its peak, dividing the region into communist and non-communist blocs, with a fault-line running right through the heart of South-east Asia. The United States’ war campaign in Vietnam was also intensifying.

Compounding the situation were the disputes between South-east Asian countries. Singapore had been forced out of Malaysia two years earlier.

Indonesia had recently wound up “konfrontasi” with Malaysia and Singapore. Malaysia and the Philippines were also locked in a dispute over Sabah, while Brunei had put down, with the help of British forces, an internal rebellion aided by Indonesia.

For Mr Lee Kuan Yew, these factors reinforced the fact that Singapore was situated in “a turbulent, volatile, unsettled region”.

The need for ASEAN

ASEAN’S formation was therefore based on an overarching rationale to counter communism and act as a unifying force during the Cold War. It was hoped that member states would also build their own resilience by managing their differences and preventing proxy wars in the region.

In From Third World To First, Mr Lee wrote: “The unspoken objective of ASEAN was to gain strength through solidarity ahead of the power vacuum that would come with an impending British and later a possible US withdrawal.”

It was clear that the leaders — Mr Lee, former Indonesian President Suharto and former Malaysian Prime Ministers Hussein Onn and, later, Mahathir Mohamad — shared an innate understanding of the situation and different sensitivities of the region during ASEAN’s formative years.

Mr Lee’s views of the grouping were shaped by Konfrontasi with Indonesia and the Vietnam War. To him, ASEAN was a vehicle that would not only buttress regional solidarity, but also maintain a delicate power balance between Indonesia, the largest power in South-east Asia, and its neighbours.

Mr Lee ensured that the voices of smaller states were not lost. In a 1999 Asiaweek interview, he said: “We don’t pick quarrels. As ASEAN’s smallest member, we have to stand our ground, or our rights will be rolled over.”

When Vietnam invaded and occupied Cambodia in 1978, for example, Mr Lee was the first to write to then Thai Prime Minister Kriangsak Chamanan and Chair of ASEAN to urge the organisation to stand united and steadfast in supporting the Cambodian coalition and pressure Vietnam to withdraw its troops. He later wrote: “We had spent much time and resources to thwart the Vietnamese in Cambodia because it was in our interest that aggression be seen not to pay.”

Mr Lee saw ASEAN as a means to preserve the security of a small state like Singapore, especially with its predominantly ethnic Chinese population, in a sea of Malays. He helped cement the fact that Singapore is a South-east Asian country by recognising China in 1990 only after Indonesia had done so.

By using his friendship with Suharto and being sensitive to Indonesia’s feelings on thorny issues, such as China, Mr Lee was able to carve out a reasonable space for Singapore in ASEAN. Mr Lee wrote in From Third World To First: “Under Suharto, Indonesia did not act like a hegemon. This made it possible for the others to accept Indonesia as first among equals.”

Future of ASEAN

Later, with the collapse of communism, the reality of a multi-polar world and China’s growing heft in the region, ASEAN continued to maintain a strategic balance of power in the region.

The grouping engaged the world’s major powers through multilateral mechanisms such as the ASEAN Regional Forum, the East Asia Summit and the ASEAN Plus Three Meeting, which includes China, Japan and South Korea.

At the same time, ASEAN needed a new force for unity: Economics. This economic imperative started in 1992, after Mr Lee had stepped down, with the launch of the ASEAN Free Trade Area and its goal of economic integration.

ASEAN enlarged from 1997 onwards to include new members. By the 2003 ASEAN Summit, member states would call for closer economic integration and the creation of an ASEAN Community by 2020, a goal which has now been advanced to 2015.

As one of the founders of ASEAN, Mr Lee had from the start engaged with new members and encouraged their opening and entry into the regional group and international community. For example, ASEAN and Singapore had worked hard on the Cambodian question early on, with Mr Lee personally travelling the world to highlight the issue.

Yet, Mr Lee also rapidly adjusted to the realities and possibilities of the post-Cold War world. In a 1999 Asiaweek interview, he said: “There’s no great ideological divide between the ASEAN countries. The communist system is gone. We are just varying degrees of democracy or of authoritarianism. Every country wants economic and social progress. After the severe financial and economic setbacks, nobody’s got time for ideological or expansionist issues.”

Vietnam, in particular, came into focus for him. Mr Lee first visited it in the early ’90s and had been appointed an adviser to its government. He then made visits to the Singapore-Vietnam industrial parks that were opened as part of inter-governmental cooperation.

Vietnam’s successful integration into ASEAN’s fold is proof that economic integration is indeed the path forward. Already, the organisation has announced that it has achieved 80 per cent of its goals in the ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint to be an integrated market by 2015.

As Mr Lee put it in 2011’s Hard Truths to Keep Singapore Going: “The logic of joining markets is irrefutable and it will happen.”

When, and not if, economic integration occurs, it would certainly validate Mr Lee’s confidence in ASEAN’s ability to serve as a viable force for unity and prosperity.