Smart people are not always the best investors

Bloomberg and the Wall Street Journal recently reported how Harvard University’s endowment fund was hit with a staggering US$1.1 billion (S$1.45 billion) write-down on its natural resources holdings. Yet Harvard’s money managers are likely ranked among the best and brightest in the investment business.

Conventional wisdom says that if you are smarter, you should be able to spot better investment opportunities and thus, invest better.

Bloomberg and the Wall Street Journal recently reported how Harvard University’s endowment fund was hit with a staggering US$1.1 billion (S$1.45 billion) write-down on its natural resources holdings. Yet Harvard’s money managers are likely ranked among the best and brightest in the investment business.

In 2017, the Boston Globe reported that Harvard’s seven top-paid endowment managers earned a combined US$58 million in 2015, during a period when Harvard’s investment performance lagged behind the rest of the Ivy League endowments.

How can this be? Conventional wisdom says that if you are smarter, you should be able to spot better investment opportunities and thus, invest better. Perhaps it was just bad luck, or was it something else?

In the latest update on returns from endowments from financial research firm Markov Processes International, Harvard continued to maintain close to the bottom spot among its peers (see chart below).

On a closer look, most large endowment funds fail to beat the benchmark return of a “dumb” and passive 60-40 index portfolio (consisting of a diversified basket of 60 per cent of the United States stock market and 40 per cent of the US bond market, with about 12,000 holdings)

Professor Gilbert, a finance professor at the University of Washington, said that the mistake smart investment managers make stems from the belief that their skill and intelligence would allow them to side-step risks and mistakes that others would typically avoid.

Shane Frederick, from the Sloan School of Management at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, found out that smart people (those with high IQ scores) had the tendency to make more mistakes when problem-solving, by taking mental shortcuts as that requires less mental effort.

He also found out that smart people were more willing to gamble (take more risk) even with poor odds.

Behavioural finance and psychology experiments also point to a cognitive bias called the blind-spot bias. Everyone is prone to this irrationality, where we are better at recognising biased reasoning in others but not in ourselves.

Psychologists West and Meserve from James Madison University and Stanovich of the University of Toronto have found that the blind-spot bias is greater the smarter an individual is. As a result, most smart individuals are able to see why others have made poor investment choices, yet are unable to see their own mistakes. They are more likely to ignore the advice of peers or experts and fail to recognise when they need help.

As an illustration of this point, Eleanor Laise did a study on the investment performance of the Mensa investment club. Mensa is a non-profit organisation open only to people with IQ scores in the top 2 per cent of the population.

For the 15-year period from 1986 to 2001, the Mensa investment club managed to get an average return of 2.5 per cent annually versus the 15.3 per cent annual return of the S&P 500 index. In other words, the investment returns of a select group with IQs at the top 2 per cent of the population did 84 per cent worse than the index.

The point is not to say that all smart people are bad investors, as there are obviously smart people who have done really well.

However, everyone, smart or not, needs to be more aware that self-perceived smartness, especially if derived from past successes in their careers, need not always equate to success in investing.

We should thus not be so awed by the large armies of highly paid professional investment managers and analysts employed by large financial institutions as many of them could likewise be unaware of their blind-spot bias.

CHILDREN COULD DO IT

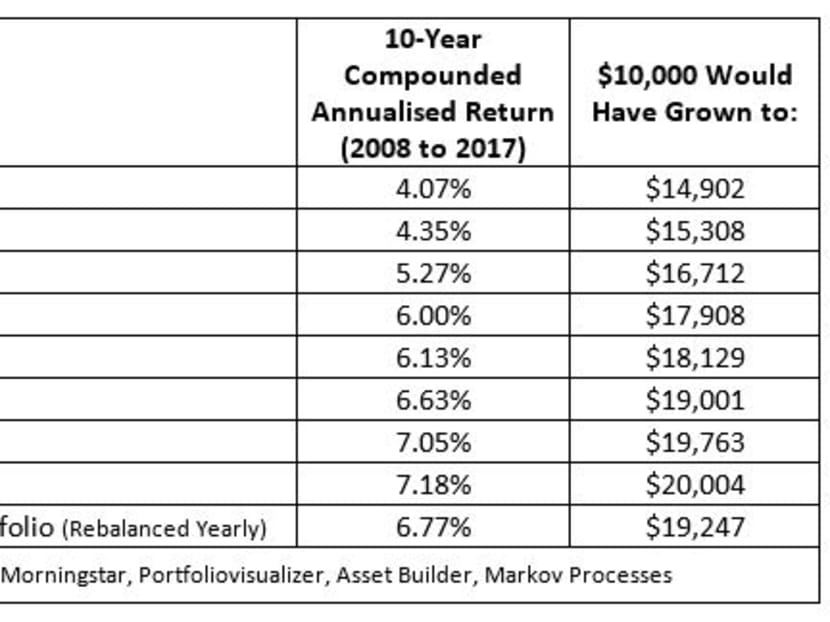

Elaborating on the reports of the Ivy League’s endowment performance, author and financial columnist Andrew Hallam conducted a fun experiment and wrote about it on the AssetBuilder website.

He asked two girls aged seven and eight to pick 20 exchange-traded funds (ETFs) from five main asset categories to construct a portfolio, of which not all were “winning” funds. He then back-tested their portfolios to see if they could beat the endowments. The results were unsurprising.

A simple diversified portfolio was able to beat the complex investment strategies employed by all these super smart professionals. The portfolios that the children chose did not constantly switch the asset allocation nor constituent funds.

So, the good news is that if children are able to beat some of the most intelligent investors on the planet with simple, proven methods, so can you.

The mechanics can be as simple as just investing in a globally diversified portfolio of index funds with an asset allocation that is most suited to one’s personal risk tolerance and then rebalancing yearly.

The more difficult part is managing one’s emotions and instinctive behaviours during volatile and uncertain markets, so that one does not fall prey to buying and selling at the wrong times.

While you may not beat all the pros each and every single year, the odds of outperforming many of them over the long term, in 10 years, for example, is good.

Remember Warren Buffet’s US$1 million bet against a basket of hedge funds? The bet ended after 10 years in 2017 with his chosen S&P 500 index gaining an average of 7.1 per cent per annum against the 2.2 per cent per annum returns of the hedge funds selected by asset management firm Protege Partners.

Back to Bloomberg’s report on Harvard, it ended with a suggestion from a group of alumni from the class of 1969. They had a simple suggestion for Harvard’s endowment chief: Invest in index funds.

That way, Harvard would have had better investment returns, and saved a whole lot of money from paying salaries to their top-notch investment teams.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Aw Choon Hui is the deputy chief executive officer of GYC Financial Advisory, a licensed financial adviser and registered fund management company.