Taking a long-term view of tuberculosis

World Tuberculosis (TB) Day has been observed on 24th March every year since 1982, when it was sponsored by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease to commemorate the centennial of Robert Koch’s discovery of the germ that causes TB.

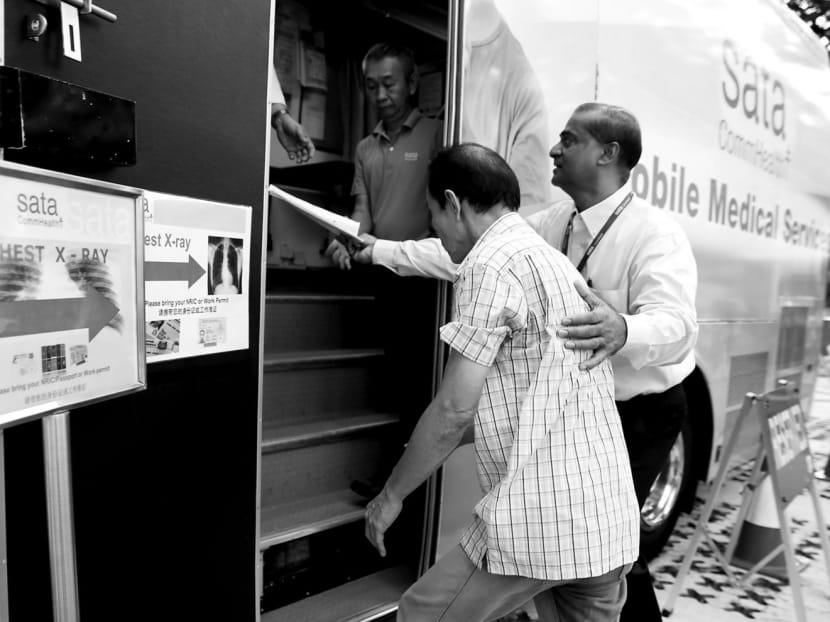

A resident enters a mobile medical services vehicle for a chest X-ray at an MOH health screening at Ang Mo Kio Avenue 3 in June 2016. TB remains an epidemic in most countries, including Singapore. More resources have been provided by the Ministry of Health to address the rise in TB rates. TODAY file photo

World Tuberculosis (TB) Day has been observed on 24th March every year since 1982, when it was sponsored by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease to commemorate the centennial of Robert Koch’s discovery of the germ that causes TB.

On that Friday evening in 1882, Koch stunned the scientists who had come to listen to him at the Physiological Society of Berlin by describing a series of experiments that conclusively attributed the disease variously known as the “white plague”, consumption, phthisis, and even lyrically as “captain of all these men of death” to a bacterium that could also cause the same disease manifestations in cattle, guinea pigs, and apes.

World TB Day reminds us that TB remains an epidemic in the majority of countries in the world, including Singapore, and it still exerts a ruinous toll on the health and economy of individuals and society.

TB can be viewed as a crude microcosm of Singapore’s development. It reflects, in equal parts, the benefits and risks of our openness to the world.

In the 19th century, many of the vagrants suffering from TB had been dumped, unwanted, onto Singapore’s shores by the Dutch East Indies government.

The growth of Singapore’s global entrepot trade brought considerable wealth to us in those days, but also increased the incidence of TB, as great numbers of working-class immigrants crammed into the congested shophouses of the inner city, where the disease took root.

In 1901, TB killed 1,700 people, cementing its status as one of Singapore’s top-killing diseases.

After the end of World War II, Singapore made a concerted effort in the 1948 Medical Plan to tackle TB through both clinical methods (surgery to collapse diseased lungs, chemotherapy, BCG vaccination, and the conversion of Tan Tock Seng Hospital into a sanatorium) and social policy (public housing development).

In this anti-TB campaign, which was bolstered when Singapore became a self-governing state in 1959, the island was able to tap into the expertise of the British Medical Research Council.

Singapore even served as a critical site for a series of seminal clinical trials during the late 1970s and early 1980s, which led to the development of the short-course multiple-drug treatment regimen that is still the standard of care today.

Similarly, when the Singapore Tuberculosis Elimination Programme was launched in 1997 to eliminate the disease, local physicians collaborated with their American counterparts to institute a comprehensive programme of directly observed therapy (Dots) and a national registry to monitor patients’ therapy, including preventive treatment for their close contacts.

The impact of the HIV epidemic on TB rates in Singapore has thankfully been small, unlike other parts of the world where a resurgence of TB was witnessed.

In the 21st century, further incremental progress was made, with continued reduction of local TB incidence rates until 2008.

The WHO estimated that only 58 per cent of the world’s approximately 10.4 million new cases of TB had access to quality TB care in 2015.

For multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) — a term used to describe infections caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates that are resistant to the two “backbone” drugs in the chemotherapy cocktail against TB, isoniazid and rifampicin — this percentage fell further to just 20 per cent.

In Singapore, however, virtually all patients with TB and even the rare few with MDR-TB have access to quality care, with social support provided to low-income patients to maximise the likelihood of treatment completion. One example of this is the “Dot & Shop” scheme — sponsored by Sata CommHealth — where grocery vouchers are disbursed to low-income individuals if they are compliant with Dots.

Nonetheless, Singapore’s TB incidence rates started to climb post-2008, after decades of decline.

Various research studies have shown that there are two primary demographic factors that account for much of this phenomenon. They are an ageing resident population and an increase in the non-resident population.

Both factors are not unique to Singapore. In countries with low TB incidence, such as western Europe, Australia and the United States, a significant proportion of their TB cases have come from those who were born in countries where the burden of TB remains high.

The effect of ageing has similarly been described elsewhere, including Japan and Hong Kong.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis can remain in one’s body for years without causing any symptoms — a condition known as latent TB infection — reactivating and causing disease only when one’s immune system becomes weakened (as in the case of HIV infection), which can occur in various ways as one becomes older.

Thankfully, infection rates in Singapore have fallen decade on decade after World War II, and the proportion of elderly that reactivate earlier contracted TB will also fall over time.

Today, in many countries, TB continually risks losing the requisite state and community support to threats posed by other more publicly visible infectious and non-communicable diseases.

Patients are also in greater personal danger due to the emergence and spread of MDR-TB around the world, a message brought home by the Parklane cyber cafe and Ang Mo Kio cluster of cases that made the news in 2012 and 2016.

Socio-economic factors such as the stigma against tuberculosis also cause a small number of patients to fail to complete their treatment, increasing the likelihood of drug resistance.

Thankfully, increased resources have been provided by the Ministry of Health to address this rise in TB incidence rates in Singapore, but it may take a few more years before the impact is seen.

It is imperative that Singapore utilises its international collaborative links, in conjunction with its national and community capacities, to deal with the persisting threat of TB, as it had done throughout its history.

Such commitment and focus must be decades-long, beyond the cycles of government leaders and business.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS:

Associate Professor Hsu Li Yang is the Programme Leader of the Antimicrobial Resistance Programme at the National University of Singapore’s Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health. Dr Loh Kah Seng, a historian and co-founder of Chronicles Research and Education, is researching the history of TB in Singapore as part of the programme at the school.