Apps and aerial dog fences on the agenda to block wayward drones

WASHINGTON — They’ve buzzed the White House, come too close to planes, attempted to airlift drugs over prison walls, and interfered with firefighters in California.

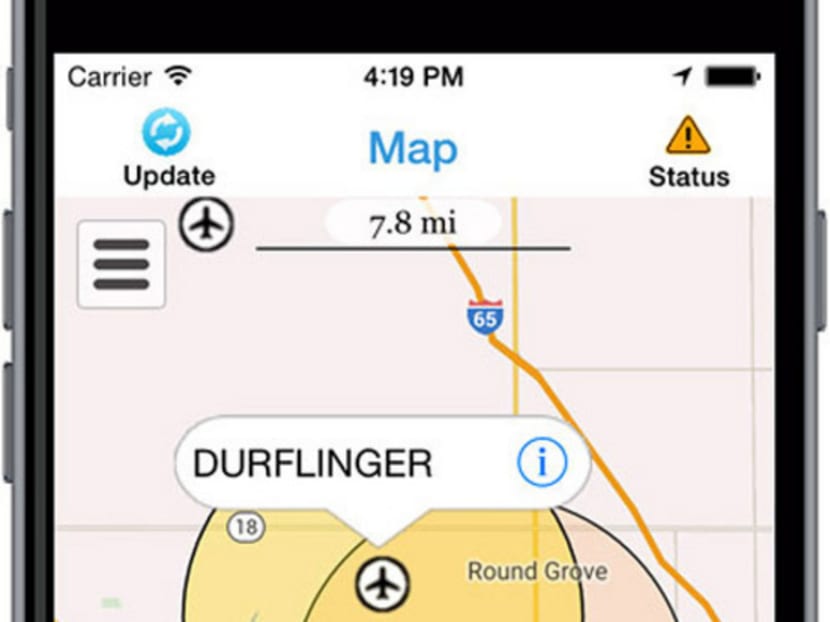

The FAA is testing a smartphone app that shows drone users where it is safe to fly. Photo: Bloomberg

WASHINGTON — They’ve buzzed the White House, come too close to planes, attempted to airlift drugs over prison walls, and interfered with firefighters in California.

In fact, drones have been involved in so many incidents that some United States lawmakers are proposing to fight technology with technology — requiring an aerial version of an invisible dog fence to block unmanned aircraft from flying in sensitive areas.

Similar to how electronic fences zap dogs to keep them within boundaries, the fence-in-the-sky uses global-positioning systems to mark no-fly zones for drones. Trouble is, the systems, known as geo-fencing, may not be effective against the growing lawlessness in the skies.

Geo-fence technology can be overridden and it won’t work on older or cheaper models, education campaigns haven’t seemed to work so far, and catching violators has proven almost impossible.

“As long as there’s YouTube and everybody’s competing for the coolest video, there’s going to be drones out there,” said Mr Jim Williams, the former chief of the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA’s) unmanned aircraft division. “My confidence isn’t high that this will go away.”

Geo-fencing holds some of the best promise to rein in drone excesses, but will hardly be a panacea as the surge of drone incidents is expected to exceed 1,000 this year.

Before geo-fencing can be mandated, the government must first write regulations, an often cumbersome process that can take years, said Mr Williams, who is now a drone-industry consultant at the law firm.

The technology also won’t work for cheaper models without GPS, he said. And as many as 1 million consumer drones have already been sold in the United States, many of which may never be updated with geo-fence boundaries, he said.

“That’s great going forward, but the ones that are out there already are difficult,” said Mr Alex Mirot, president of the Unmanned Safety Institute. His Maitland, Florida, company trains drone operators and has advised airports on steps to address the risks created by unmanned aircraft.

The geo-fencing limits are also vulnerable to being disabled or hacked, said Mr Kevin Finisterre, a computer security consultant in Columbus, Ohio, who has studied software on drones made by different manufacturers.

SZ DJI Technology, the Shenzhen-based firm that is the leading producer of consumer drones, already includes more than 6,700 restricted zones around the world in its geo-fencing software. But it still may be possible to fly DJI drones in restricted areas because in some cases the system provides a warning without halting the flight, DJI vice-president of Policy and Legal Affairs Brendan Schulman said in an e-mail. That’s because drones are allowed to fly in some normally prohibited zones if operators receive FAA approval, Mr Schulman said.

The FAA generally restricts unmanned aircraft from flying more than 400 feet above the ground, and also within five miles of airports. There have been almost 700 incidents this year in which pilots and other crew members reported seeing drones violating airspace rules, according to a database released on August 21 by the FAA.

While in most cases, pilots in traditional planes said they didn’t have to take evasive action, there was at least one possible collision with a drone, according to the FAA database.

A pilot of an unidentified small plane said he heard a loud thump on April 27 near Livermore, California. Scratches on the fuselage and propeller were found after landing, according to the FAA. In other instances, pilots said they have narrowly missed hitting unmanned craft. Airline crews in cities such as New York, Boston and Los Angeles have reported seeing drones as they prepared to land.

As a result of cases such as these, California Senator Dianne Feinstein introduced legislation in June that would require stricter regulation of unmanned aircraft. In addition to geo-fencing, drones would have to broadcast their identity, location and altitude while flying.

Such technology is justified even though it may increase the cost of drones or cause sales to decline, said Senator Richard Blumenthal, a Connecticut Democrat who supports the Bill.

“We don’t sell less expensive cars without seat belts or airbags,” Mr Blumenthal said in an interview.

New drone provisions could be included in legislation setting the FAA’s broad policy goals, which Congress is writing this autumn.

Representative Peter DeFazio, an Oregon Democrat who is the highest-ranking member of his party on the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, asked the Department of Transportation for suggestions on how to reduce drone safety incidents in an Aug 26 letter.

Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx in interviews has suggested requiring registration of newly purchased drones, while FAA administrator Michael Huerta has said the agency is looking at the feasibility of technology to identify operators. The FAA is also testing a smartphone app that shows drone users where it is safe to fly.

While such steps may make sense, especially for drone users who aren’t familiar with FAA regulations, they are relatively easy to thwart, said Mr Richard Hanson, spokesman for the Academy of Model Aeronautics (AMA).

Some people assemble drones from kits, and many are sold online by companies outside the Unites States, where enforcement would be difficult, said Mr Hanson, whose group represents 180,000 members who fly model planes.

The AMA believes the risks are being overblown and the government shouldn’t attempt a rushed response, he said.

“It’s not as easy an issue and the fixes aren’t as easy as some people try to make them,” he said.

The law enforcement arm of the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection knows how difficult it is, said Captain Richard Cordova.

There have been at least a dozen cases this year in which drones were spotted near wildfires, forcing the agency to temporarily ground its fleet of aircraft dropping water and chemicals on blazes, Capt Cordova said.

In spite of working with local police, drone operators have melted away each time and no one has been caught, he said.

The FAA has opened more than 20 investigations of drone misuse, assessing penalties in five of them.

“It’s hard,” said assistant professor John Robbins, coordinator of Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University’s unmanned aerial systems programme. “You can kind of look at it as the wild west of aviation right now.” BLOOMBERG