The Holga story: A cheap plastic camera made in Hong Kong and how it became a cult classic

A Holga 135TIM camera. Picture: South China Morning Post

HONG KONG — Holga may not be a brand name as recognisable as Canon and Nikon, nor is it as highly regarded among perfectionists as German brand Leica, but it does have a global cult following and it has influenced the way people think about photography. And surprisingly, it is from Hong Kong.

Cheap, plastic, with barely any functions and weighing only 170 grams, the Holga (a phonetic play on the Cantonese word for “very bright”, which sounds like “holgon”) is so bare-bones, users often cocoon it in duct tape or wedge cardboard under the film spool to prevent what is known in photographic parlance as “light leaks”, the streaking of photographs. Rather than showing crispness, edge-to-edge sharpness and perfect exposure, the pictures produced by the Holga are typified by distortion, lens flares and vignettes (dark gradations along the corners), and appear, by today’s standards, to be highly flawed.

And that’s just the way Holga users like it.

“Technology was becoming more sophisticated, and lenses were becoming more sharp, with more precise focusing,” Cheung says. “The Holga is not exactly out-of-focus – a certain part is in focus and a certain part is not. That plastic look of the image – I still haven’t found the right word, but let me use ‘dreamy’ – provided an alternative.”

“People realised that these kinds of images could be powerful. It is the same reason people like the filter apps on phones – they do not have to look at the images as reality,” Cheung says.

Users lauded the Holga as a tool with which to create visual poetry, akin to Impressionist paintings, but the cameras fan base remained small throughout the 1990s.

Then photojournalists such as David Burnett and Teru Kuwayama started using the Holga, raising its profile dramatically. At the peak of sales, in the late 2000s, plastic boxes with “Holga” written on them were selling at a rate of two million a year.

Lee Ting-mo was born in Hong Kong in 1930. He conceived the Holga in 1981. He designed and produced the first model, a medium-format 120 film camera, and all subsequent versions until it met its demise, in 2015.

People realised that these kinds of images could be powerful. It is the same reason people like the filter apps on phones – they do not have to look at the images as reality Martin Cheung

Lee was employed by Japanese camera manufacturer Yashica in 1967, to oversee production at its Hong Kong factory. Two years later, he established his own company, Universal Electronics Industries, initially to produce capacitors but eventually moving into flash units.

Lee, who had studied locomotive technology, began winning praise for his WOC 250x flash, which caught the attention of Agfa, a German company that was interested in establishing a factory in Hong Kong to manufacture flash units.

“They asked me to reform our factory, and set very strict regulations,” says Lee, when we speak in his office in industrial Hung Hom, Kowloon. “Of course, they were a very famous company, so we accepted their demands.

“At the start of the 1970s, there was only our company and one other making external flash units in Hong Kong, but at the end of the ’70s, you know how many factories were making flash units? Thirty more!”

Japanese camera maker Konica put a sudden end to that explosive growth with the Pikkari, a camera with a built-in flash, a concept other manufacturers then copied.

“At the beginning of the 1980s, so many factories closed very fast, only two or three companies remained,” recalls Lee. “At that time, we moved from Kwun Tong to Hung Hom, and we employed 200 workers. We dismissed so many workers – more than 100.”

While Universal struggled to survive by selling flash units to professional photo studios, Lee racked his brains for a new product. Recognising that China was beginning to open up, Lee wanted something to sell to consumers there who were looking for foreign products. He would develop an affordable camera for the masses, he decided.

“In China, there were only a few factories making cameras, but they were really big companies, belonging to the government. Their equipment was very good; I think most of it was imported from Russia. They produced cameras at a very high price, and the quantity was very small. Only national companies had the money to buy them.”

This led to the development of the Holga 120, a camera that would be affordable for many. It would surely be a hit in China, where 120 film – which produces square images in a higher resolution and with more detail than those produced by the more common 35mm film – was being produced, Lee thought.

“However,” he says animatedly “I didn’t sell even one Holga to the Chinese market! They wanted something from the outside. At first I expected very good business. They didn’t want a 120; they wanted a 135 format. I was very confused.”

Having already produced a batch of 120-format cameras, Lee tried to interest buyers in Japan, the United States and Europe. Some people saw value in the Holga as a teaching tool, due to its simple construction, and Lee sent one to Lomography, an Austrian company that specialises in the distribution of toy cameras, such as the Diana, another from Hong Kong, which was launched by the Great Wall Plastic Factory, in Kowloon Bay, in 1955.

Overseas sales remained modest until American photojournalist Burnett used a Holga to shoot a presidential campaign. A dramatic monochrome shot of Democratic candidate Al Gore won him the 2001 White House News Photographers Association’s Eyes of History contest.

“It was interesting because at first someone said, ‘The pictures are not so good,’ but then after [Burnett took the prize] people said, ‘This camera is very special,’” says Lee. “It changed suddenly.”

Initially, news magazine editors had a “psychological barrier” when it came to Holga images, says Kuwayama, a New York-based photojournalist who uses Holgas to shoot in war zones and during humanitarian crises. But, over time, they began to ask for them, he says.

“Most of the places I worked in were very remote — and in many of them, like Afghanistan or northern Pakistan, the people I was encountering may have never seen any kind of camera before, so they weren’t judgmental about what type of camera it was,” says Kuwayama, from his home in New York.

Working in the West was a different story, however.

“It was quite common for people to be surprised and dismissive when they saw my equipment, or sceptical that I was really a professional photographer.”

Not that Kuwayama was deterred. The initial attraction was practical; the Holga was light and robust, so he could always carry two, one in each pocket. Then Kuwayama developed a deeper appreciation: “The camera has a voice, a really distinct, visual voice. It requires a more deliberate, conscious practice. The parameters of its simplicity [read limitations] require a photographer to choose conditions carefully.”

“As an analogy, in places like Iraq and Afghanistan, I lived among some very proficient fighters and hunters of different military forces. They all used a vast spectrum of tools, ranging from laser-guided missiles to automatic rifles, extremely sophisticated and powerful pieces of gear, but every single one of them also carried a knife,” Kuwayama says.

“We develop systems of incredible complexity and efficiency, and the most advanced equipment tends to become obsolete the most rapidly. It’s the most basic tools that endure. That’s how I think of the Holga. The Holga is a knife.”

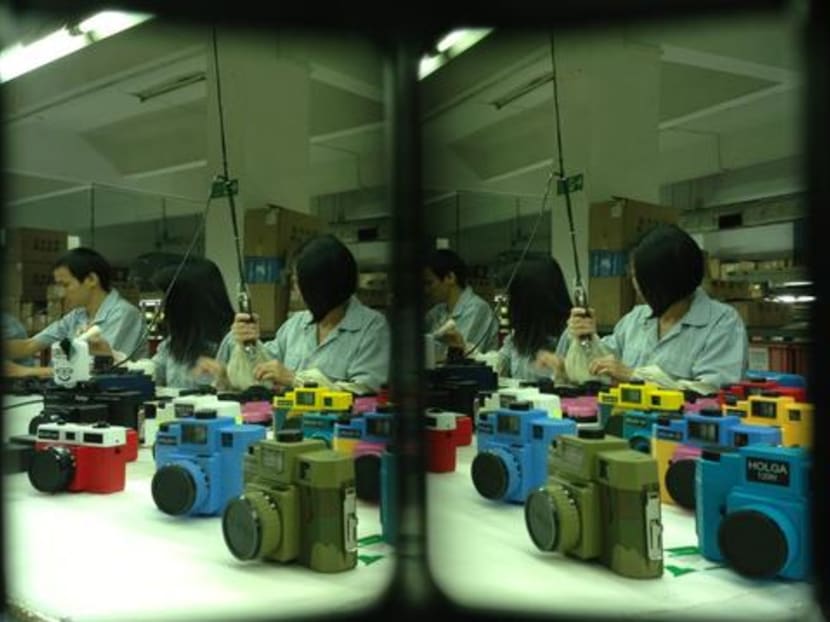

Thanks to the powerful work of Kuwayama and others, the Holga found a degree of popularity. Lee responded by producing more than 100 models: some with a built-in flash; 135 panoramic units; some bearing cute designs – Lee is fond of cats; and some with gel filters. He experimented with colours and formats but the fundamental feature – the plastic lens – was retained in every model.

“There was a recognition of [the Holga] being unique to Hong Kong,” recalls photographer Justin Lim, when we speak at his Kandid Soho studio in Sheung Wan, on the western side of Hong Kong Island. Lim experimented with toy cameras in the mid-2000s, using techniques such as cross-processing to create sci-fi-esque images in otherworldly colours.

“Hong Kong is always trying to make itself out to be a leader in tech, banking and law, but we should be proud that something creative, used worldwide, has come out of the city. I have always used the Diana and Holga with a sense of pride,” says Lim.

“People are interested in very cinematic things in Hong Kong because it has a huge cinematic culture and heritage. If you look at a Wong Kar-wai movie, it has obviously been filmed on a top-end camera, but it has that toy-camera feel, with the saturation of the colours.”

Similarly, for Simon Wan Chi-chung, a photographer who recently exhibited a 30-metre scroll of exquisitely crafted Holga images at Hong Kong City Hall, using a locally made camera was a conscious choice.

“[The work] is about Hong Kong’s landscape; of course I must use a camera made here,” says Wan, half-jokingly, when we speak at his exhibition, “107 No Man Islands”, organised by the Hong Kong Museum of Art.

To get his shots, the photographer travelled alone by kayak to 107 of Hong Kong’s uninhabited islands, Holga in hand – a brave undertaking considering the temperamental nature of the camera.

“The reason a Holga feeds my concept is because I take pictures, I work hard, but they might not come out [as expected],” Wan says. “Only if the lighting condition perfectly fits the setting on the camera, then you have a perfectly exposed negative – just like life.”

Another attraction of the Holga was its cost.

“I play a lot with [the concepts of] consumerism, ownership; I play with the value of art, not in terms of money,” says Wan, who used the cheapest camera and kayak he could find. Moreover, he adds, laughing, “the low cost meant that even if I dropped the camera into the sea, it wouldn’t have been a problem.”

This affordability has created a culture of “hackers”, people who play around with the construction of their toy cameras, customising them to take other film formats, for instance.

Cheung has fashioned his Holga into a pinhole camera, and he believes many hackers in Asia equate such manipulation to the childhood pastime of constructing plastic models, such as Gundam robots.

In 2015, Holga closed its factory, which had, in 1990, been moved to Changping, in China’s Guangdong province, and most of the tooling equipment was thrown out. Lee kept the equipment to make the 120-format camera, though, “as a souvenir”.

Sales had been falling, “but not very fast; even when digital cameras came out, people still wanted to take pictures using film – they even liked the cameras without a flash”, says Lee.

He experimented by producing cellphone filters, such as plastic cases, and Holga lenses for digital SLR cameras, but it was the increasing difficulty of obtaining and developing film that accounted for the camera’s demise. Also, Lee retired.

Now, however, film is experiencing something of a renaissance among young Hongkongers, in much the same way as vinyl records and other analogue media are.

Showa, a shop in Mong Kok, caters to millennials who are experimenting with film photography. The branding is chic and the shop uses social media to promote the appeal, stating that, “film photos have a textural quality that can’t be replicated with digital”.

Both owner Alan Mok Hoi-lun and Lui Pak-yu, who is in charge of public relations, take great pains to explain to customers the concept of film cameras, and are often bewildered by the questions they are asked.

“‘Do you have Wi-fi with film cameras?’ and, ‘Do you have an effect to make your face look pretty?’ You never know what they will ask,” says Lui. “They ask, ‘Do you have a new film camera?’ They think it is a brand new camera, a new concept.”

Showa received the last of the company’s stock, and is now one of the only places in the world where you can buy a new Holga.

“We have the most models and colours in Hong Kong, but if we sell one, we have one less,” says Lui, “We can’t restock any more, and it’s sad that these [new fans] only took an interest after Holga closed.”

Attempts to resurrect the Holga are already under way, however, and they include a digital model, made by Hong Kong start-up Smartgears. The analogue model is being resurrected by another Hong Kong factory, Sunrise, which is making the 120N model, having licensed the Holga brand. The camera is already available for pre-order on Freestyle Photographic Supplies and other specialist websites, and it is expected initial orders will be filled early next month.

It remains to be seen whether the new models will win the approval of Holga enthusiasts and live up to the reputation of the magic plastic box. SOUTH CHINA MORNING POST