In ‘watershed moment,’ YouTube blocks extremist cleric’s message

WASHINGTON — For eight years, the jihadi propaganda of Anwar Awlaki has helped shape a generation of United States terrorists, including the Fort Hood gunman, the Boston Marathon bombers and the perpetrators of massacres in San Bernardino, California, and Orlando, Florida.

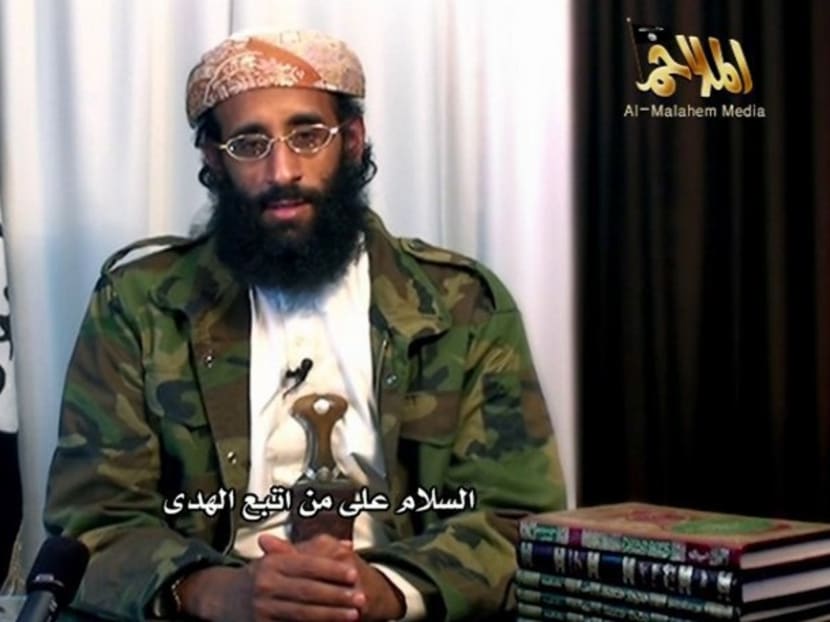

A video grab image released by SITE Intelligence Group shows a clip of Yemeni-American cleric Anwar Awlaki. Under growing pressure from governments and counter-terrorism advocates, YouTube has drastically reduced its video archive of Awlaki, who remains the leading English-language jihadi recruiter on the internet six years after he was killed by a US drone strike. Photo: AFP

WASHINGTON — For eight years, the jihadi propaganda of Anwar Awlaki has helped shape a generation of United States terrorists, including the Fort Hood gunman, the Boston Marathon bombers and the perpetrators of massacres in San Bernardino, California, and Orlando, Florida.

And YouTube, the world’s most popular video site, has allowed hundreds of hours of Awlaki’s talks to be within easy reach of anyone with a phone or computer.

Now, under growing pressure from governments and counter-terrorism advocates, YouTube has drastically reduced its video archive of Awlaki, an American cleric who remains the leading English-language jihadi recruiter on the internet six years after he was killed by a US drone strike.

Using video finger-printing technology, YouTube now flags his videos automatically, and human reviewers block most of them before anyone sees them, company officials say.

A search for “Anwar al-Awlaki” on YouTube this fall found more than 70,000 videos, including his life’s work, from his early years as a mainstream American imam to his later years with Al Qaeda in Yemen.

Today, the same search turns up just 18,600 videos, and the vast majority are news reports about his life and death, debates over the legality of his killing, refutations of his work by scholars or other material about him.

A small number of clips of Awlaki speaking disappeared after The New York Times sent an inquiry about the change of policy last week.

“It’s a watershed moment on the question of whether we’re going to allow the unchecked proliferation of cyberjihad,” said Mr Mark Wallace, chief executive of the Counter Extremism Project, a research organisation that has long called for Awlaki’s recordings to be removed from the web.

“You just don’t want to make it easy for people to listen to a guy who wants to harm us,” said Mr Wallace, a former diplomat.

He said the fact that much of Awlaki’s presence was lectures on Islamic history did not justify keeping it on YouTube. “It’s an insult to Islam to say the teaching of the religion can’t stand the loss of a preacher who was also the leading propagandist of jihad in English,” he said.

Scrutiny has been rising for internet companies, including Facebook, Twitter and Google, which owns YouTube. They had long argued that they were merely neutral platforms with no responsibility for what users posted.

But they were quick to remove copyrighted material, child pornography and beheading videos, for example, which posed an obvious threat to their business. They have slowly stepped up the removal of extremist content, spurred on after 2014 by the Islamic State’s use of Twitter to recruit fighters.

The prolific presence on YouTube of Awlaki, who in his later years called for attacks on the US and Americans, has been a subject of complaints since November 2009, when he wrote on his website that Army Major Nidal Malik Hasan was a “hero” for fatally shooting 13 people at Fort Hood, Texas.

Born in New Mexico to Yemeni parents, Awlaki spent half his life in the US and spoke excellent English. As a popular young imam in Denver, San Diego and a Washington DC, suburb, he recorded lecture series that were eventually best sellers among Western Muslims — notably his 53-CD boxed set on the life of the Prophet Muhammad.

After leaving for London in 2002, however, he gradually embraced the view that the US was at war with Muslims, who had a religious duty to fight back. After evidence emerged that he had recruited and coached the young Nigerian who tried to blow up an airliner over Detroit on Christmas Day in 2009, President Barack Obama ordered a legal review and then placed him on the terrorist kill list.

Awlaki and three other members of Al Qaeda were killed in a drone strike in Yemen in September 2011. But his death on Mr Obama’s orders made him a martyr in the eyes of many admirers, who posted more and more of his work on YouTube.

Much of it was the early, mainstream material, which clearly did not violate YouTube’s “community guidelines.” But especially after Awlaki’s death, fans often labelled even his early material as the work of the martyr killed by the US. The number of videos on YouTube presenting or celebrating his work more than doubled from 2014-2017, even as investigators found his decisive influence in most of the major terrorist attacks in the US and some in Europe.

The Counter Extremism Project, in a series of reports, documented his posthumous power and complained about YouTube’s recommendation tools, which often suggested Awlaki’s more sinister recordings to people who watched material on Islam or sampled his history talks.

YouTube was slow to remove even his most explicit calls for violence. Though the company first promised publicly to take such material down in 2010, Awlaki’s “Call to Jihad,” a 12-minute talk calling on Western Muslims to join the jihad in the Middle East or carry out attacks at home, remained easily available on YouTube until last year.

As pressure mounted, however, the company recently decided to treat Awlaki the way it treats terrorist organisations, with a near-total ban, according to company officials. The officials agreed to discuss the policy change but declined to be named, citing security concerns.

YouTube said the initial decision to purge any particular video was made by human reviewers. But once the decision has been made, a “hash function,” a kind of digital fingerprint, is created to automatically rid the site of additional copies of the same video.

The officials noted that YouTube, according to its published rules, “strictly prohibits content intended to recruit for terrorist organisations, incite violence, celebrate terrorist attacks or otherwise promote acts of terrorism.” But they decided that in the special case of Awlaki, all of his recordings should be removed.

“I’ve seen a major drop-off of his work on YouTube,” said Mr Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens, research director at George Washington University’s Programme on Extremism and author of a forthcoming book on Awlaki. “They deserve credit for that.”

Some civil libertarians cautioned about the dangers of censorship, even by a company rather than a government.

“The motivations that lead any individual to commit an act of violence are very complex,” said Ms Faiza Patel of the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University’s law school. “To pin it on one guy’s videos seems very simplistic.”

Mr Meleagrou-Hitchens noted that Awlaki’s work remains easy to find elsewhere on the web for those seeking it. A weekend search for Awlaki’s “Call to Jihad,” for instance, instantly brought up the video on a French site, Dailymotion; on the Internet Archive; and on a Pakistani’s Facebook page.

Nonetheless, Mr Meleagrou-Hitchens said, the popularity of YouTube and its automated recommendations have made it an especially pernicious platform for the cleric.

“The fact is that if you really want Awlaki videos, you’ll find them,” he said. “But if he’s less available on YouTube, fewer people are coming across him who aren’t actually seeking him out.” THE NEW YORK TIMES