The Big Read: Indonesia needs a new approach to blunt ISIS’ appeal, experts warn

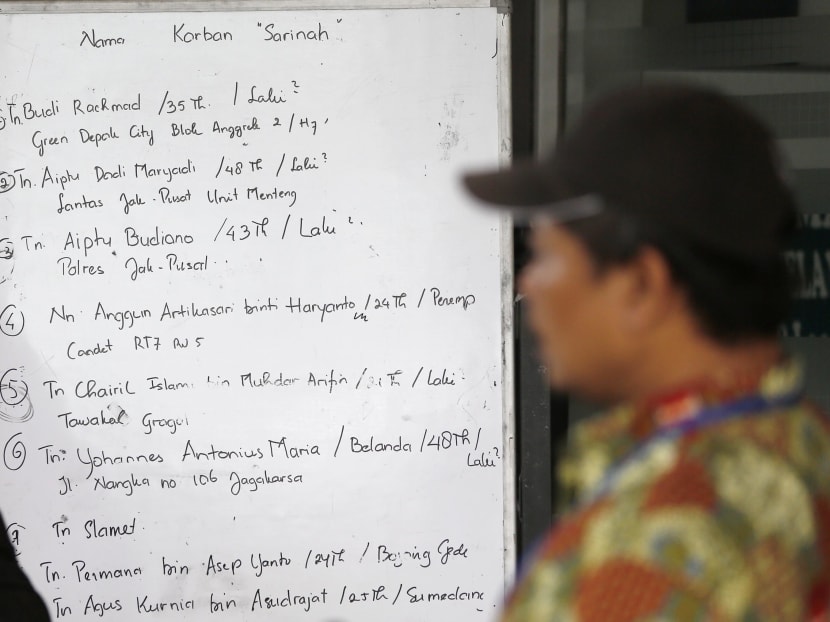

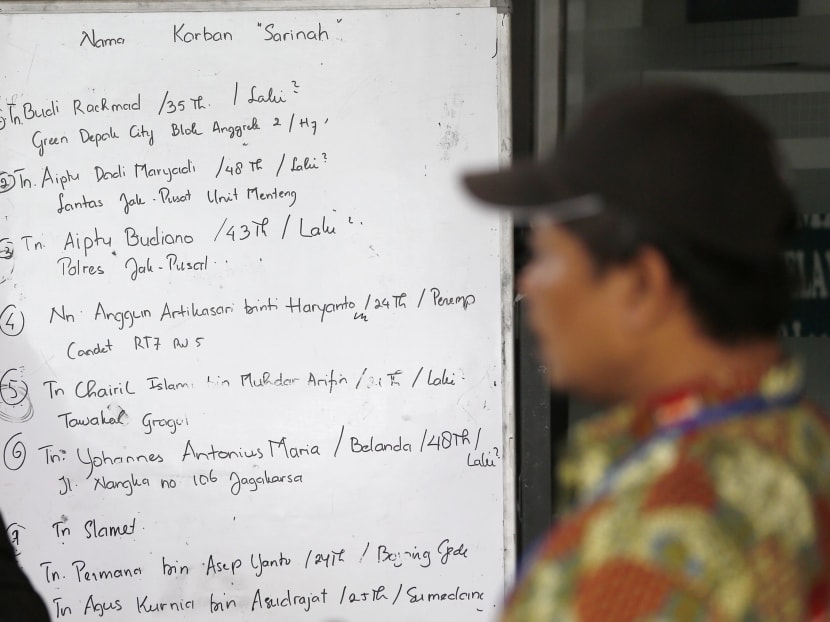

A list showing casualties from last Thursday's bombings in Jakarta. Photo: Raj Nadarajan

JAKARTA — Hours after Islamic State (ISIS) militants struck central Jakarta with bombs and gunfire last Thursday, bird-meat seller Karim wheeled his pushcart to his usual spot, some 200m away from the site of the attack, despite being “a bit afraid”.

Business was poor that day as people stayed away. But the initial shock from the transnational militant group’s first major strike in South-east Asia, a game changer for the region’s security outlook, quickly faded for Mr Karim and most Indonesians.

“My friends are still running their businesses and I just did the same,” said the 38-year-old a day after the attack. “No, I’m not afraid now.”

Neither, apparently, were thousands of Jakarta residents, who turned up en masse at the blast site near the popular Sarinah mall in a defiant show of solidarity and what experts consider the resilience of Indonesian society.

“Indonesian society is far more resilient than outsiders realise, for the reason that Indonesians have been exposed to all kinds of calamities from earthquakes (to) tsunamis and political upheavals,” said Associate Professor Farish Ahmad-Noor of the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) at the Nanyang Technological University.

Such resilience, he and other analysts suggest, will likely help dampen the appeal of ISIS in the world’s largest Muslim country, Indonesia.

However, in the last three years, several countries in the Middle East and North Africa have seen thousands of their nationals head to Iraq and Syria to fight for ISIS. Elsewhere, those who could not travel to Syria have taken up ISIS’ call to launch attacks at home, such as last November’s terror siege in Paris.

Security experts say ISIS poses a serious threat in Indonesia and must be tackled with more resources. But at the same time, they point out that economic, social and religious conditions in Indonesia are vastly different from those in countries where ISIS sympathies have grown dramatically.

For one, Indonesia largely practises a moderate brand of Islam. The country is also not in the grips of extreme political or economic upheavals, noted RSIS associate research fellow Romain Quivooij.

Young Indonesians, experts say, are more concerned about upward mobility than armed jihad.

“Many young Indonesians today aspire to better standards of education and upward social mobility, and violence is seen as counterproductive and detrimental to their own interests,” said Assoc Prof Farish.

Still, there are growing concerns about ISIS’ presence and capabilities in Indonesia which, alongside Malaysia, rank among the most likely locations for a South-east Asian base for the militant group.

According to The Soufan Group, a New York-based security intelligence firm, no more than 500 Indonesians have travelled to Syria and Iraq to fight for ISIS. The figure, while small compared to Indonesia’s population of 250 million, potentially makes Indonesians the largest South-east Asian contingent in ISIS.

“One ISIS fighter is already one too many,” said Ms Susan Sim, vice-president for Asia of The Soufan Group.

Several Indonesian militant groups, including the Jemaah Islamiyah (JI), have already pledged allegiance to ISIS. The JI was behind the 2002 Bali bombings, and plotted to attack embassies and key infrastructural targets in Singapore.

Indonesian security forces have largely been successful in disrupting the JI network and arresting key figures like the group’s spiritual leader Abu Bakar Ba’asyir. But the prisons where many JI terrorists are held have, ironically, become fertile breeding grounds for radicalisation and ISIS’ recruitment efforts.

This has raised concerns in the region as Indonesia has no preventive detention laws which can be used against the large number of terrorist prisoners, hundreds of whom have either already been released since January 2014, or are eligible for release or parole by end of this year.

“These include JI-linked terrorists. They were previously involved in plots against Singapore and Western targets in Indonesia,” Singapore’s Home Affairs Minister K Shanmugam said in an extensive speech this week, where he warned of “an explosion of terrorism, based on religion” in South-east Asia.

In Thailand, the Philippines and Myanmar, grievances and socio-economic conditions of the minority Muslim populations make the terror threat more potent.

Mr Shanmugam added: “The proliferation of charismatic preachers who advocate intolerance, violence; the availability of such teachings on the Internet; the glorification of terror, violence, beheadings - these international events, trends are fusing perfectly with fertile conditions in this region, to beget violence and terror.”

What can Indonesia do to better deal with the threat of ISIS? Recommendations by analysts suggest stronger efforts are needed at home — to boost family ties, encourage the moderate majority to be more vocal, launch more efforts to counter extremist ideology, and enact reforms to Indonesia’s prison system.

A recent report in the Jakarta Post newspaper noted that terrorist convicts in the Nusakambangan prison island in Central Java, including Abu Bakar Ba’asyir, routinely receive visitors, making it possible for them to spread radical teachings.

“Overcrowded and disorganised penitentiaries staffed by underpaid and opportunistic officials have created environments in which extremism has flourished,” said RSIS senior analyst Cameron Sumpter. “Well-meaning rehabilitation and disengagement initiatives have been introduced by both government and civil society groups, but until the system itself is cleaned up, they will struggle to bring positive change.”

He added that former prisoners need to be better monitored after their release, even if such efforts are expensive and labour-intensive. Mr Sumpter’s suggestion has been bolstered by news that Afif, one of the alleged ISIS militants who attacked Jakarta last week, planned and carried out the deed less than six months after his release.

The task of counter-terrorism cannot be left to the police alone, as is virtually the case now in Indonesia, said Mr Noor Huda Ismail, research director of the Jakarta-based Institute for International Peace Building.

Parents and family members need to play a bigger role in monitoring youths susceptible to radical teachings, he noted, adding: “The least we can do is go home, spend quality time with the kids — go back to the very foundation of society, which is family.”

Mr Noor Huda also suggested that civil society or the creative industry should do more to highlight the plight of disenchanted ISIS fighters who have returned from Syria — as cautionary tales to those who are contemplating similar journeys.

“Hey dude, I’ve been there, it was horrible, you shouldn’t go,” he added.

Jakartans were quick to declare through memes and social media posts that they were not afraid in the wake of last week’s attack in the heart of the Indonesian capital city.

But Mr Syamsul Arif Galib, co-founder of Makassar International Peace Generation, said the silent, moderate majority needs to speak out more often, and not allow a small extremist minority to be heard to a disproportionate extent.

“The majority (in Indonesia) are moderate, but they are more like a silent majority,” he added. “We need to be more proactive to say, we are against terrorism and extremism.”