The Big Read: Malaysia’s dangerous turn down the road of religious politics

SINGAPORE — The furore over an anti-cross protest at a church in Selangor that has grabbed headlines over the past week is a development in Malaysian politics that has been brewing for some time and is a result of actions taken by the dominant Malay party in the country as it seeks to shore up its popularity among the majority race in the nation.

SINGAPORE — The furore over an anti-cross protest at a church in Selangor that has grabbed headlines over the past week is a development in Malaysian politics that has been brewing for some time and is a result of actions taken by the dominant Malay party in the country as it seeks to shore up its popularity among the majority race in the nation.

Analysts and observers said race and religion have always featured in Malaysian politics, but the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) has until now focused on the racial angle as leverage to strengthen its grip on power — the most obvious example being the bumiputra policy. But this has changed after UMNO’s poor showing in the 2013 general election, where the party lost the popular vote; the battle lines are now also drawn around religion.

Analysts added that this does not bode well for Malaysia. Social order, which is already tenuous, will come under further pressure as positions harden and moderate segments of society push back against those politicising race and religion.

“Since race has slowly become ineffective as a way to polarising society to strengthen certain parties’ hold on power, it has over the past few years become the fashion to use religion as the means by which the division of Malaysian society can continue,” Dr Ooi Kee Beng, deputy director of the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies said in an email interview with TODAY.

“It has come so far now that it is not so much about negotiating as outright resistance. The traditional elite will be speaking out more and more. The question is, since it involves religion, the countervailing attacks on them may get very nasty,” added Dr Ooi.

The strong reaction from a broad coalition of moderate Muslims and politicians against the anti-cross protest not only exposed the rift between ultra and moderate Muslims, it could be a harbinger of things of come.

In the protest last Sunday, 50 Muslims had staged a demonstration outside a new church in Petaling Jaya, reportedly claiming that its display of the cross was a challenge to Muslims and could influence the young. Out of fear, the church removed the cross transfixed on its façade.

The protest sparked outrage among politicians, moderates, netizens and various religious groups, who pressed the government to take action against the protesters before others were emboldened to commit similar acts at other places of worship.

An under-pressure Prime Minister Najib Razak has said that the police will investigate and 10 protestors have been called up for questioning so far.

“This cross protest is merely one in a series of many similar incidents. It has now become a trend where certain pro-government groups would play up racial and religious issues one after another with the intention to cause tension,” Mr Zairil Khir Johari, an opposition Member of Parliament from the Democratic Action Party (DAP), told TODAY.

“This is also in line with the recent right-wing bent of the government, especially in the reintroduction of indefinite detention without trial and the tightening of the Sedition Act. We are seeing a government that is using the pretext of racial and religious instability as justification to reinforce its grip on power.”

There are various signs of how race and religion have become politicised in Malaysia.

In January last year, 351 copies of the Bahasa Malaysia and Iban-language Bibles were seized from the Bible Society of Malaysia’s (BSM) bookshop in Petaling Jaya by Selangor Religious Affairs Department (JAIS) officers and the police.

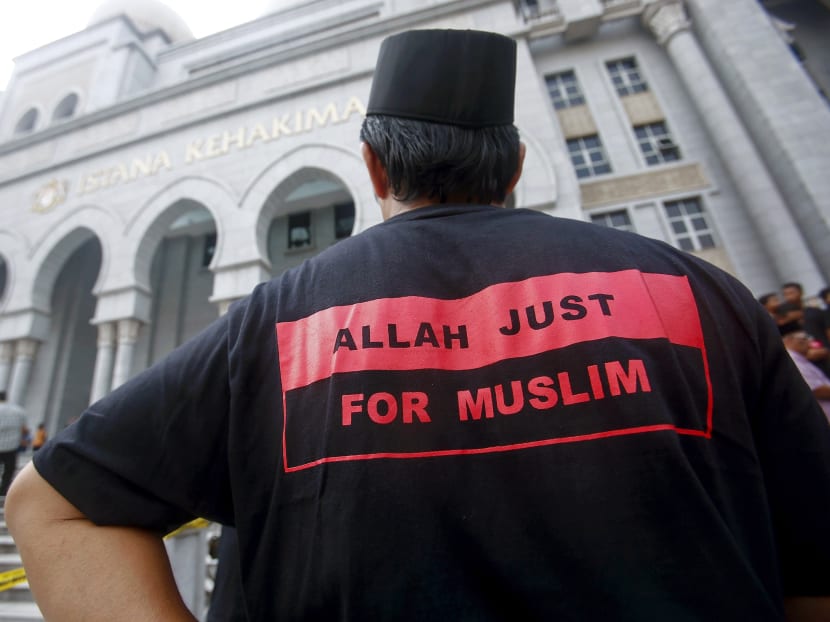

The JAIS raid came after a Malaysian court ruled that the Arabic word “Allah” was exclusive to Muslims. The books were returned in November to the Christians in Sarawak, but not the Peninsula-based BSM, on the condition that the bibles for Sarawak Christians would not be distributed in Selangor.

Earlier this year, Agriculture and Agro-Based Industry Minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob called for Malaysians to boycott Chinese traders for allegedly refusing to reduce prices of goods.

Despite a public outcry against Mr Ismail, Prime Minister Najib Razak did not censure him for the racist remarks, in a clear sign that the UMNO President cannot afford to antagonise ultra-nationalists in the party.

PUSHBACK FROM MODERATES

Racial politics has always been a fixture in Malaysia, and this is especially evident in the affirmative action policy of bumiputra (or sons of the soil), also known as the New Economic Policy (NEP) introduced in 1971. Under the bumiputra policy, extensive privileges were given to Malays and the East Malaysian natives, over Chinese and Indians. Privileged access to education, employment, equity ownership and even the buying of houses were ostensibly meant to correct the bumiputra’s backwardness as an outcome of negligence under British rule.

The real reason for the bumiputra policy, a brainchild of former Prime Minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad, was to maintain Malay supremacy in the country.

While the bumiputra policy officially ended in 1990, its longevity is quite apparent. How the majority of the civil service is still made up of Malays, while the bulk of university places continue to be set aside for the bumiputras are just some examples of how racial politics continues to be a reality of daily life.

Indeed, UMNO has continued to play the racial card to suit its own political purposes over the years. Mr K Kesavapany, Distinguished Affiliated Fellow of the Asian Research Institute (ARI) in the National University of Singapore, said that “the race card won’t go away”.

“Who will want to give away the (bumiputra) privileges once they have gotten used to them? … For UMNO to battle PAS (Parti Islam Se-Malaysia) and PKR (Parti Keadilan Rakyat), the race card is essential. Ultimately, UMNO positions itself as the bulwark against the Chinese so that it can continue to appeal to the Malay base.”

Observers say that UMNO is desperate to shore up support among its Malay base following the party’s poor performance in the 2013 general elections, where it lost the popular vote with a mere 47 per cent tally, but managed to scrap through the parliamentary elections with 60 per cent of the seats.

This was despite UMNO campaigning on the platform of a “1Malaysia” common identity in a bid to win over the Chinese, as well as Malaysia’s good economic performance and the government’s handouts of US$2.6 billion (S$3.47 billion) to poor families.

“With the Malay community becoming urban and a bigger majority, a large part of the economy not owned by Chinese or foreigners, using the threat to the Malay race as a way of uniting Malays against non-Malays, no longer works as well as before, especially when both (ruling and opposition) coalitions are Malay-led,” said Dr Ooi of ISEAS.

Another factor is how many middle-class Malays have now become Islamised, pointed out Mr Kesavapany.

“Religious fundamentalism, whereby Muslims adhere more closely to the teachings of Islam means that UMNO has to hold on to them or PAS will benefit,” he added.

Just over half of 29 million Malaysians are of Malay origin, a quarter are of Chinese descent and the rest are Indians or other indigenous groups. Before the bumiputra policy, many of the Malays were rural dwellers with lower income vis-à-vis the Chinese population which tended to congregate in urban areas. But the income gap has been narrowing.

With the politicisation of race and religion, the pushback from moderate segments of Malaysian society has been growing. The Group of 25 (G25), a group of Malay former high-ranking civil servants has been increasingly vocal on the growing Islamisation of Malaysia and the impacts this has on Malaysia’s social stability.

In an open letter in December, G25 spoke out against the “lack of clarity and understanding” of Islam’s place within Malaysia’s constitutional democracy, as well as a “serious breakdown of federal-state division of powers, both in the areas of civil and criminal jurisdictions”. The group also called on the government to “send a clear signal that a rational and informed debate on Islamic laws in Malaysia and how they are codified and implemented are not regarded as an insult to Islam or to the religious authorities”.

According to Dr Mohamed Nawab Mohamed Osman, Head of the Malaysia Programme at S Rajaratnam School of International Studies, this was the first sign that Malaysian society was getting worried about growing extremist elements.

“Prior to the G25, what we saw were small groups such as the Sisters of Islam and Global Movement of Moderates that served as of voices of reason,” he observed.

SOCIAL ORDER UNDERMINED

There have been instances when social order has been undermined as moderates and extremists disagree with each other over religion, even if the situation has not reached tipping point.

Following the JAIS bible raid, about 100 Selangor UMNO members participated in a rally near a church in January last year, after the church’s pastor indicated that he would continue to use the word “Allah” during worship.

Earlier this month, there was an outcry when five top executives and editors of The Malaysian Insider were arrested in a sedition probe over a report published by the news outlet about the Conference of Rulers’ rejection of a proposed amendment of a federal law to allow hudud law to be enforced in Kelantan. PAS, which rules Kelantan, is pushing for hudud law - an Islamic criminal code that prescribes punishment such as amputation for crimes such as stealing, to be implemented in the state. The Bill to amend the federal law will be debated in parliament next month.

“There is fear that rule of law, which is already badly undermined, will weaken even more going forward,” said Dr Ooi of ISEAS.

Speaking to the media in Singapore this week, Malaysia’s Youth and Sports Minister Khairy Jamaluddin Abu Bakar played down such fears and the anti-cross protest last week.

“I wouldn’t say rise in politicisation of religion (in Malaysia). But I think in any multi-religious country, not just Malaysia but multi-religious countries all over the world, these flashpoints will happen from time to time. It is not the norm and I think it is an isolated incident,” he said.

“I think the message the government wants to send is that we are decisive in investigating this and in making sure nobody else does it. I don’t think there can be tolerance for such things and I don’t think it’s indicative at all of a general pattern of intolerance in Malaysia.”

Mr Zairil, the opposition lawmaker who is also executive director of the Penang Institute, said that owing to historical legacy, Malaysian politics has always revolved around the politics of identity - race, religion being most prominent.

“Hence, instead of class fault-lines, we see a dichotomy between ethno-religious concepts, ie Malay-Muslim vs non-Malay non-Muslim”.

On what the politicisation of race and religion mean for Malaysian politics going forward, he said that “it is unhealthy, especially in an environment of suppressed media and controlled information.”