China scolds Australia over its fears of foreign influence

SYDNEY — China accused Australia of hysteria and paranoia on Wednesday (Dec 6), a day after Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull unveiled a series of proposed laws to curb foreign influence in Australian politics.

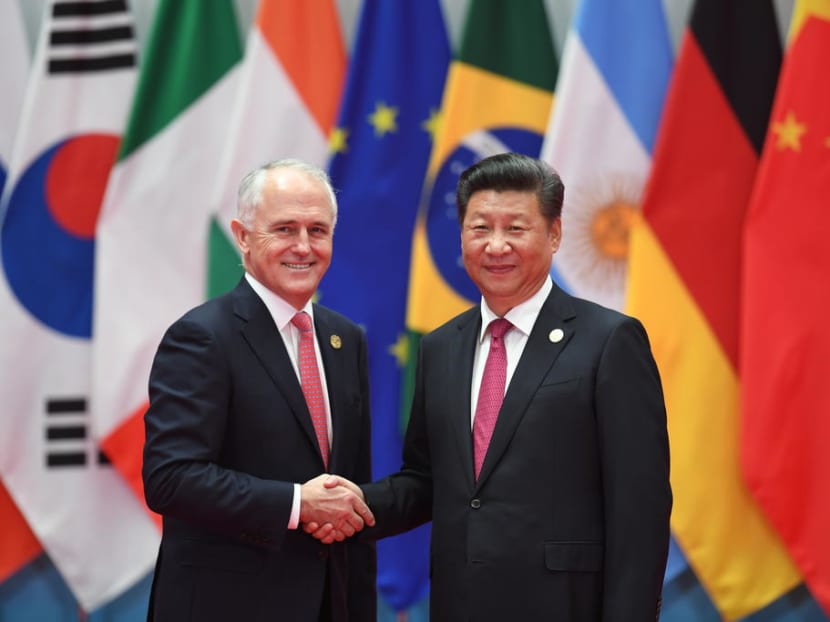

Australia’s Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull shakes hands with China’s President Xi Jinping (R) before the G20 leaders’ family photo in Hangzhou last year. China accused Australia of hysteria and paranoia on Wednesday (Dec 6) after Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull vowed to ban foreign political donations in a move to curb external influence on its domestic politics. Photo: AFP

SYDNEY — China accused Australia of hysteria and paranoia on Wednesday (Dec 6), a day after Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull unveiled a series of proposed laws to curb foreign influence in Australian politics.

The new legislation, modelled on American laws that ban foreign campaign donations and require registration of foreign agents, had been widely expected after a drumbeat of stories in the Australian news media about the perceived threat of Chinese interference.

It was not the legislation that the Chinese statement directly condemned, but rather the media accounts that prompted it, as well as the public debate around the issue.

Both have zeroed in on China as a threat, accusing the country of trying to exert influence through political donations and pressure applied to Chinese students at Australian universities.

“Some Australian media have repeatedly fabricated news stories about the so-called Chinese influence and infiltration in Australia,” the Chinese Embassy in Australia said in an English-language statement on its website.

“Those reports, which were made up out of thin air and filled with cold war mentality and ideological bias, reflected a typical anti-China hysteria and paranoid (sic).”

The statement added that “irresponsible remarks” by some Australian politicians and government officials had damaged trust between the countries.

“We categorically reject those allegations,” the embassy said.

“China has no intention to interfere in Australia’s internal affairs or exert influence on its political process through political donations. We urge the Australian side to look at China and China-Australia relations in an objective, fair and rational manner.”

The statement pointed to strong discontent from China’s leaders in Beijing, and it amounted to a warning for Australian politicians against continuing to portray China as an enemy. But experts said the statement might only heighten concerns about China’s influence and damage its already tarnished image in Australia.

“Over all there is a sense of overreach by China, and the way this statement is worded will compound that,” said Rory Medcalf, head of the National Security College at Australian National University.

“This statement will be seen as unhelpful and provocative in some circles in Australia.”

Mr Turnbull had told reporters in Canberra on Tuesday that foreign powers were making “unprecedented and increasingly sophisticated attempts to influence the political process” in Australia and the world.

He had cited “disturbing reports about Chinese influence”.

Mr Turnbull’s remarks came as concern grows that Beijing may be extending its soft power efforts in the country and as relationships between Australian politicians and Chinese government interests become increasingly contentious.

Earlier this year, Australia’s intelligence chief identified two prominent businessmen of Chinese descent, who have donated millions of dollars across the political spectrum in recent years, as possible agents for the Chinese government.

In June, Fairfax Media and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation reported on a concerted campaign by China to “infiltrate” Australian politics to promote Chinese interests.

Since then, Australia has been engaged in an intensifying discussion about whether to accept or resist China’s dominance in the region.

This week, a politician from Australia’s opposition Labor party was demoted from government having been found to have warned a prominent Chinese business leader and Communist Party member that his phone was being tapped by intelligence authorities.

Australia’s loose and opaque campaign finance laws have made the country especially vulnerable to outside influence. Australia and neighbouring New Zealand are among roughly a third of countries worldwide that allow foreign donations to political parties. Such donations are prohibited in the US, Britain and several European countries.

It is unclear to what extent China is concerned about the new laws proposed by Australia against foreign influence.

One provision would require people working on behalf of another country to register with the Australian government, as is mandated in the US. Among the other proposals, there are plans to create an offence known as unlawful interference in Australia’s political system, which would include behaviours — as yet unspecified — that harm the national interest.

Some people who are especially concerned about Chinese interference in Australia have welcomed the proposals as much-needed counterweights.

“This is an exciting development indeed, although it should have happened earlier,” said Feng Chongyi, a Chinese-born professor at the University of Technology Sydney who has often criticised China’s suppression of dissent.

China may see the laws as inevitable, he said.

If that is the case, some experts argue, the embassy’s statement Wednesday may in fact be an effort to pressure the Australian news media, and to influence how the media is perceived by the Chinese Australian community.

The embassy statement focused intensely on media accounts of “so-called Chinese influence and infiltration,” and argued that Australia’s discussion about China’s role has “unscrupulously vilified the Chinese students as well as the Chinese community in Australia with racial prejudice, which in turn has tarnished Australia’s reputation as a multicultural society.”

John Fitzgerald, a professor at Swinburne University who spent five years representing the Ford Foundation in China, said the Chinese government seemed to be trying to portray itself as the defender of Chinese Australians against the Australian news media.

“The embassy itself is stirring up concerns within the Chinese Australian community that have no foundation,” Mr Fitzgerald said, adding: “The media is not attacking the Chinese Australian community. The media is being very specific about Communist Party interference in this country.”

So far, Australian officials have chosen not to escalate the argument.

Julie Bishop, Australia’s foreign minister, said in a statement Wednesday evening that the Australian government “enjoys a respectful and constructive relationship with China.”

Mr Medcalf said the statement from the Chinese Embassy had one line that could be helpful: “China has no intention to interfere in Australia’s internal affairs or exert influence on its political process through political donations.”

“That is a statement China will be held to,” he said. “Let’s hope China is serious.” AGENCIES