Exit from EU looms over UK elections

LONDON — Mr Ian Robinson, the co-owner of a small investment firm in London, is watching Britain’s general election this Thursday with unease.

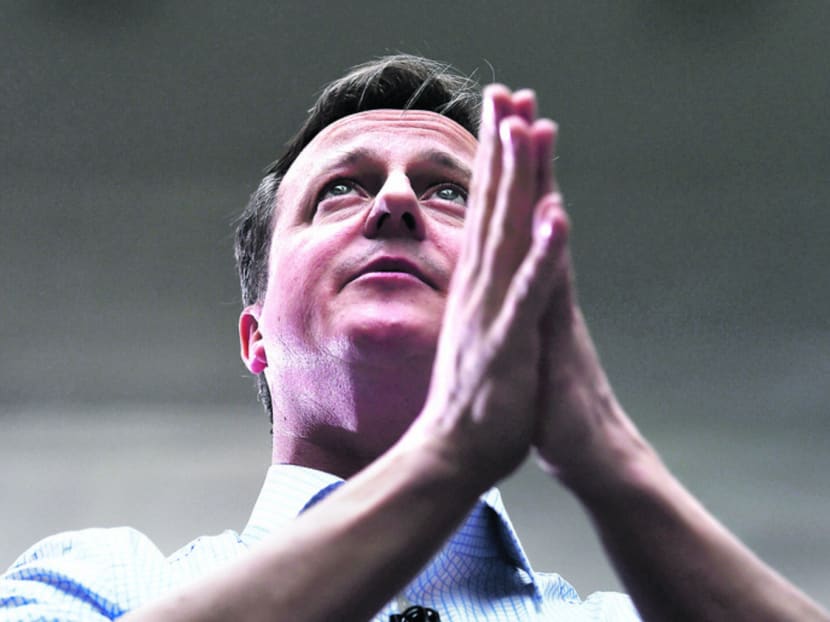

Mr Cameron described a referendum as a ‘red line’ issue and said he would not be a partner in a government with a party that did not accept that vote. Photo: Reuters

LONDON — Mr Ian Robinson, the co-owner of a small investment firm in London, is watching Britain’s general election this Thursday with unease.

A victory for Prime Minister David Cameron’s Conservative Party may bring Britain a step closer to leaving the 28-nation European Union, a move many companies fear would cause damage by increasing the cost of doing business on the continent and eroding London’s role as a global financial hub.

Mr Robinson said leaving the EU would make even the most basic things more difficult for businesses in Britain, forcing him to apply for licences in each country where he operates, rather than getting a single permit from British regulators. “Leaving the EU would be a disaster,” he said in the offices of Kinson Capital, which manages assets and provides advisory services for banks and hedge funds. “Financial services and a lot of businesses work on an EU passport.”

Mr Cameron promised to hold a referendum on EU membership in 2017 as he sought to blunt the rise of the UK Independence Party (UKIP), which said Britain should leave the bloc so it can stem the tide of immigrants from Europe and return all decision-making back to London from EU headquarters in Brussels. While the British campaign has focused mostly on issues such as the economy and healthcare, uncertainty over Britain’s possible exit — informally called Brexit — may curtail investment and rattle financial markets until the issue is resolved.

“Brexit is probably the biggest single source of uncertainty right now for UK investors,” Mr Daniel Vernazza, an economist at UniCredit Bank, said in an email. “The Conservatives have pledged an in-out referendum by the end of 2017, so it could be a multi-year period of uncertainty.”

Only last month, HSBC, one of the world’s biggest banks, said it was considering moving its headquarters out of the UK, partly because of the EU debate.

Britain joined the EU in 1973, bringing the bloc to nine members. Today, the EU is made up of 28 countries and, with more than 500 million people, is the world’s largest economic bloc.

Historically, Britons have mostly wanted to remain in the EU. But while the UK’s EU membership comes with advantages — such as unfettered access to a ¤13.9 trillion (S$20.7 trillion) market — it also comes with conditions that many in Britain are now finding onerous.

Of particular concern is one of the EU’s founding principles: That citizens of any EU country can live and work in any other member state. After the EU expanded into former communist countries of Eastern Europe in 2004, Britain saw a huge increase in migrants seeking work.

Opinion polls show that UKIP, once a fringe party, may receive more than 10 per cent of the May 7 vote as a result of its focus on immigration and the EU. In an election in which Britain’s traditional two-party system has broken down, those votes may cost Mr Cameron his job.

The Prime Minister said he wants Britain to remain in the EU, but only if the bloc is reformed. He wants to limit the free movement of labour so migrants have the right to work outside their home countries, but do not have an automatic right to claim benefits.

“What I’m doing is putting the country first and saying the people of the UK should be able to have a choice about whether they want to stay in Europe on a reformed basis or leave,” he told the BBC. “It’s an in-out referendum by the end of 2017. It’s right for our country and it’s right for Europe, too.”

Mr Cameron went so far as to describe a referendum as a “red line” issue and said he would not be a partner in a government with a party that did not accept that vote. That stance would sit poorly with the Liberal Democrats, which has partnered the Conservatives in Mr Cameron’s own current government.

Proposals for reform have so far received little support from other European leaders, including German Chancellor Angela Merkel. European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker said last week the EU would consider only minor changes.

While the EU is talking tough, it too has a lot to lose should Britain leave, as London is Europe’s pre-eminent financial centre. Britain is also the EU’s second-biggest economy after Germany and was the world’s fastest-growing developed economy last year.

“One thing’s for sure: Businesses and policymakers across the continent will be watching very closely to see how the dust settles (after the election),” said Ms Sacha Romanovitch, chief executive-elect at Grant Thornton’s United Kingdom arm.

The election is so close, however, that even if Mr Cameron wins, he may not get the majority needed to secure a referendum on the EU. UKIP’s support has plateaued and Labour leader Ed Miliband has said he is in favour of the EU. But until there is clarity on the issue, which could take weeks, businesses and investors will be on edge. AP