Summer of horror: String of attacks in Europe fuels tensions

LONDON — Nearly every day seems to bring a new horror to the streets of western Europe, leaving innocent men, women and children dead or broken, fuelling political and social tensions and creating what some are already calling the summer of anxiety.

A wreath outside a church in St.-Étienne-du-Rouvray, a suburb of Rouen in northern France. Photo: AP

LONDON — Nearly every day seems to bring a new horror to the streets of western Europe, leaving innocent men, women and children dead or broken, fuelling political and social tensions and creating what some are already calling the summer of anxiety.

Death and injury have been dealt out by truck, axe, handgun, machete and bomb. The victims have included families out for a night of fireworks on the glittering French Riviera, teenagers hanging out at a McDonald’s, tourists on a train, pop music fans at a concert last Sunday and a priest in a church on Wednesday.

Four of six attackers in less than two weeks professed loyalty to the Islamic State (IS), but none appear to have been directed by the radical group, and all of the assaults seemed to blur the line between ideological terrorism and violence driven by anger, grudge or mental instability.

That very murkiness — the absence of a centrally organised plot or a singular villain to blame — has made it all the more difficult for France, Germany and the rest of Europe to know how to respond.

The lack of straightforward answers has made things trickier at a time of political flux in Europe. Even before the latest string of attacks, the continent was seeing a rise in nationalist and anti-immigrant sentiment, and far-right parties were using the atmosphere to try to gain new legitimacy and power. Populist, anti-immigration sentiment was a powerful factor in Britain’s vote last month to leave the European Union (EU).

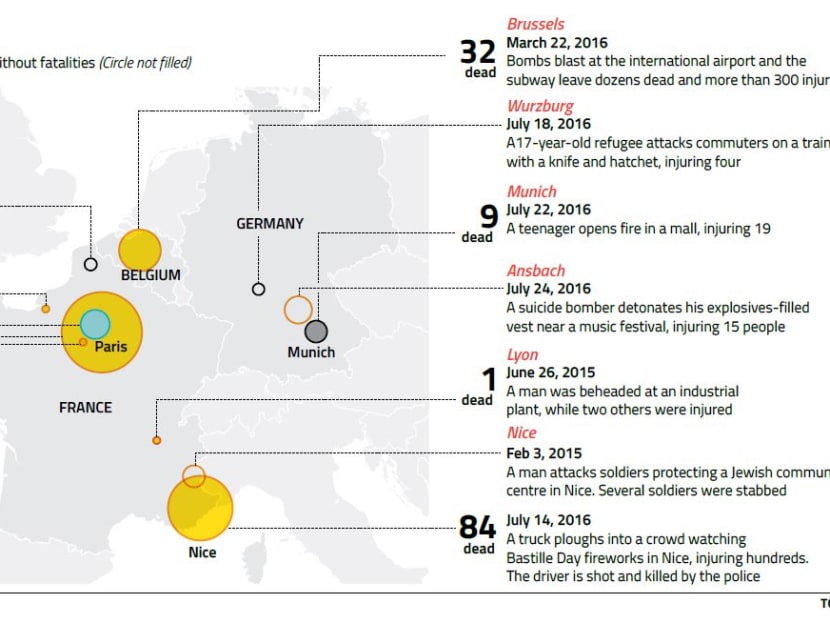

(Click to enlarge)

The recent surge in high-profile violence has only given further opportunities to those who advocate taking a tougher line on immigration by Muslims, in many ways echoing the platform being promoted by Mr Donald Trump in his presidential campaign in the United States. Over the weekend, Prime Minister Viktor Orban of Hungary spoke highly of Mr Trump, saying the Republican nominee’s proposals for fighting terrorism were just what Europe needs.

In France, which displayed remarkable unity after two terrorist attacks in 2015, there has been growing political infighting and finger-pointing since the July 14 attack in Nice that killed 84 people. In Germany, the latest attacks have further strained ties between Chancellor Angela Merkel’s conservative party and its ally in the southern state of Bavaria, where there has long been simmering opposition to her decision last year to admit one million asylum seekers.

Concern about the security and social ramifications of a new surge in migrants coming to Europe from Syria, Afghanistan and other poor and war-torn countries has left the EU with reduced leverage in dealing with President Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey as he cracks down on opponents in the wake of a failed coup this month. Mr Erdogan had agreed to a deal with the EU to hold back the tide of asylum seekers, a deal that Europe is deeply reluctant to endanger, especially with new security concerns attached to the migrants.

The same sorts of attacks have occurred elsewhere. But the concentration of attacks over less than two weeks in Europe has given the issue particular resonance on the continent.

Finding answers is in part a familiar security and intelligence challenge. But it is also in some cases a problem of immigration, assimilation and tolerance. And it is a reminder of the lure of the burst of fame, or infamy, available to troubled, violence-prone people in an age of social media and instant global communication.

“If you turn every individual into a self-contained agent, some will take unpleasant initiatives and act out their fantasies in real time, but they still feel the need for an anchoring identity,” said Mr Franois Heisbourg, chairman of the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

For some, he said, that is jihad. “It can happen in Orlando and Nice,” he said, “and without a lot of prior consultation or structure or networking.”

Ali Sonboly, the 18-year-old who killed nine people in Munich on Friday, may have been Iranian-German, but he took his inspiration in part from Anders Behring Breivik’s massacre five years ago in Oslo, Norway, which was driven by the hatred of a white supremacist. Sonboly “wanted to make his mark as an individual” by hacking into Facebook to entice people to McDonald’s, “the intertwining of complete barbarity and utter modernism,” Mr Heisbourg said.

Sonboly was acting not as a state or an organisation but as an individual, and individual actors are extremely hard for security services to stop. Yet their individual acts, captured on smartphones and sent around the world, can resonate louder than any gunshot or explosion.

The attack in Nice, France, was carried out by a Tunisian-born man with a rented truck. It has set off a new battle over blame and added another volatile element to the early stages of a presidential campaign where the governing Socialists, led by President Franois Hollande, are falling further behind the right and far-right.

The fierce and open debates over security and accountability are a sharp contrast to the reaction in France to last year’s attacks, when there was an effort to create a sense of political and national solidarity in the face of terrorism.

The national political reactions are playing out against a backdrop of global change in which terrorism is only one element.

“The world has been changing and we see that manifested in many ways, with new power centers, the power of the individual and the corporation, the disenfranchised finding a new voice and a sense that the governing infrastructure is no longer fit for purpose in today’s world,” said Ms Xenia Wickett of Chatham House, a London foreign-policy research institution.

Institutions, she said, are struggling to deal with new challenges from Islam, inequality, terrorism and globalisation. “We’re trying to manage that change and people don’t like change,” she said. “That’s the new normal, and it makes us very anxious until we can find a new one.” THE NEW YORK TIMES