Madiba magic: The genius of Nelson Mandela

The “old man” was angry. His lips were pursed, his head held high, his Olympian gaze stony.

The “old man” was angry. His lips were pursed, his head held high, his Olympian gaze stony.

When Nelson Mandela finally started speaking, his words were even more clipped than usual. It was the admonitory wrath of a headmaster. It was infused with the empathy of one who appreciated all too well the rage of his audience, yet knew that if South Africa was somehow to emerge intact from the ravages of apartheid, it had to be tamed.

It was August 1993. Three-and-a-half blood-soaked years had passed since that diamond-bright afternoon when Mandela was released after 27 years in prison under apartheid. The first all-race elections set for the following April seemed impossibly distant against the backdrop of threats of secession from the white Afrikaner right and daily bloodshed in the townships.

Before Mandela, in a ramshackle stadium in one of Johannesburg’s desolate townships, thousands of “comrades” rattled makeshift weapons and bayed for revenge. Scores had died in the previous few days in street battles against a rival party. Yet, the silver-haired septuagenarian gave no ground.

“If you have no discipline, you are not freedom fighters and we do not want you in our organisation,” he said. “I am your leader. If you don’t want me, tell me to go and rest. As long as I am your leader, I will tell you where you are wrong.”

He stared, they muttered, shuffled their feet — and backed down.

THE PROPHET WHO DEFIED EXPECTATIONS

For long years Mandela had been a shadowy symbol of hope, known only from his fiery record in the 1950s and 1960s, his inspirational speech from the dock when on trial for his life, and a grainy picture of him in the exercise yard on Robben Island prison in Cape Town’s Table Bay.

As the day of his release in February 1990 had drawn near, some confidants worried he might disappoint. Many in the African National Congress (ANC) were outraged he had been negotiating with the apartheid rulers and feared he had gone soft. Business people fretted he would be a Rip van Winkle figure clinging to the socialism he had espoused before being imprisoned. He had, after all, a record as something of a firebrand.

How wrong they all were.

Far from embittering or ossifying him, captivity had steeled him for the challenges ahead, he made clear. While unbending when he wanted to be, as his sometime adversary Mr F W de Klerk ruefully recalls, and deeply loyal to ANC traditions, he had the vision and courage time and again to break with his party’s orthodoxies — in particular over negotiating with his jailers and jettisoning socialism.

He was to be even more remarkable than the ANC had suggested. His history as a freedom fighter and political prisoner was merely the warm-up act to his greatest role of all: The apostle of reconciliation who would seduce the Afrikaners into relinquishing power and lead South Africa back into the world. In the bleak years between his release and democracy, he was an itinerant prophet of reconciliation, delivering homily after homily intended to bind his divided nation together. He could be a ponderous speaker. Yet, the force of his leadership far outweighed his oratory.

One day he would lecture enraged radicals. The next he would address white irredentists. Time and again, all but the most embittered would balk at confronting him as he worked his magic: One moment grand and aloof, every inch the descendant of his family’s chiefly clan, the next joking and teasing, the ultimate street politician yet always a model of old-fashioned courtesy.

‘I’M NO SAINT’

Now that the country has safely navigated 19 years of democracy, it is too easy to forget there was nothing inevitable about South Africa’s fairy tale.

His unwavering style of leadership has led many to regard him as a modern Gandhi. Yet, while he at times revelled in the rapture, this description irked him. He was the first to say he was not a saint.

He after all championed the ANC’s adoption of the “armed struggle” — even if this was initially a largely symbolic move. He neglected his family in pursuit of his drive to end apartheid, a source of deep sadness later in his life.

He was, to the end, an immensely human figure who loved life and laughter and was subject to the same weaknesses and foibles as the rest of us.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu, his friend and fellow Nobel Peace laureate, was one of the first to question the world’s sanctification of “Madiba” — his clan name and how he liked to be known. Archbishop Tutu appreciated long before it became commonplace that the cult of Mandela risked blinding people to the colossal problems facing South Africa.

“He is only one pebble on the beach, one of thousands,” he said halfway through Mandela’s term in office. “Not an insignificant pebble, I’ll grant you that, but a pebble all the same.”

The “Arch” was right. The otherworldly image of Mandela may have been what the world wanted to believe but, great humanitarian and moral authority as he was, he was foremost a brilliant politician.

HIS POLITICAL BRILLIANCE

Reconciliation was not a spontaneous miracle, as some imagined, emanating from the magnificence of his soul. Rather, the seduction of the Afrikaners was plotted in his cell as a way to win power.

He pondered many times that his long imprisonment gave him the time to reflect on how he should lead. It was there that he urged fellow prisoners to learn Afrikaans, on the theory you could better defeat your enemy if you spoke their language.

“I knew that people expected me to harbour anger towards whites,” Mandela later wrote when recalling the morning after his release. “But I had none. In prison, my anger towards whites decreased, but my hatred for the system grew.”

Twenty-three years later, the “rainbow nation”, as Archbishop Tutu exuberantly labelled the post-apartheid society, is still a work in progress. While relations are transformed, South Africa remains riven by racial and socioeconomic inequality.

It was always going to take more than an inspirational leader to overcome the legacy of centuries of discrimination. Yet by force of personality and example, Mandela encouraged the belief that reconciliation really was possible.

Sometimes there was a touch of theatre to his drive, such as when he invited the widows and wives of former Afrikaner Nationalist leaders to tea at his residence. Some in the ANC suggested he had gone too far when he travelled to a remote whites-only settlement to visit Betsy Verwoerd, whose husband Hendrik had provided the ideological underpinning of apartheid and enacted some of its most repressive laws.

A wrinkled 94-year-old, she spoke with a quavering voice as she offered him coffee and syrupy koeksisters. At an impromptu press conference on her stoep in searing heat, a black journalist pointedly insinuated that Mandela was frittering away his time in office. He replied testily that his drive had cost him little time and yet, bound the nation together.

Mandela knew how important it was to keep Afrikaners loyal. He also knew South Africa could ill-afford what had happened at independence in neighbouring Mozambique: A mass exodus of whites with their skills and capital. So he masked his anger over the past.

His campaign reached its zenith in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a project of astonishing ambition aimed at exorcising the troubled past. Then,there was the 1995 Rugby World Cup when he won the hearts of so many Afrikaners with his adoption of “their” game, rugby, inspiring the Springboks to victory against the favourites, all but by his exuberant passion alone.

ARISTOCRAT, REVOLUTIONARY, STATESMAN

So what was the secret to the “Madiba magic” and his seduction routine? Intrinsic to his genius was his Protean persona. One day he came across as an old-fashioned aristocrat, another as an impassioned revolutionary leader, and the third as a world statesman.

While like any experienced politician he knew how to play an audience, unlike so many leaders in the age of television there was little artifice about his guises.

Rather, they were rooted in his extraordinary life. In his lectures to angry “comrades”, his genes as the scion of chiefs were to the fore. It was as if he were upbraiding a rowdy village assembly, as his forefathers must have done in the past.

Drawing on the precepts he learnt as a child, and also from his missionary teachers, he had an old-world charm. He could be a stickler for protocol. He chided Members of Parliament in the German Bundestag for not wearing ties and lectured his ministers and ANC members on punctuality.

Yet, this was the man who launched a sartorial revolution with his loose-flowing “Madiba shirts” and who was famous for his abhorrence of pomposity and love of the gentle tease. Who else could telephone the Queen and address her as “Elizabeth”?

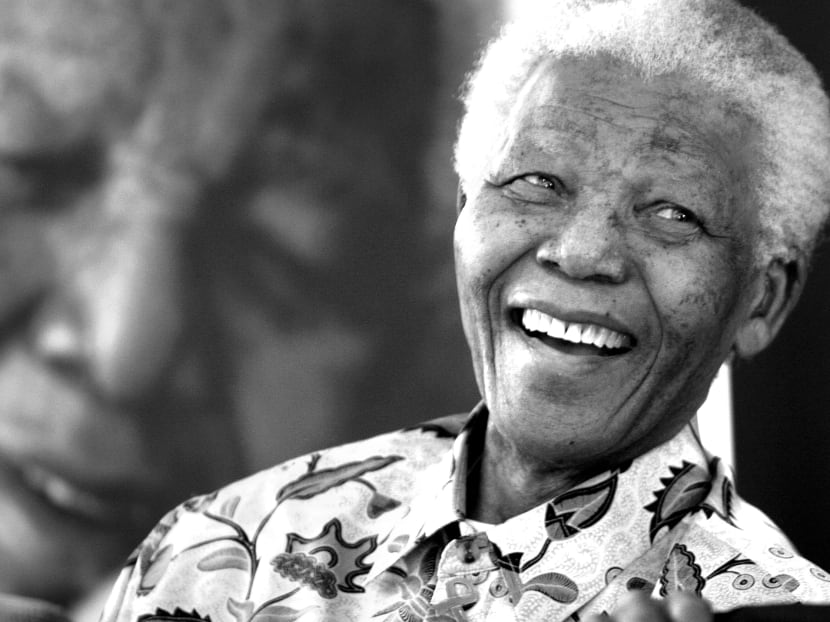

The ability to make people like you is merely the first lesson for aspirant politicians. But even so, Mandela had a particular genius for the glad-handing side of politics, primarily because his warmth seemed genuinely uncontrived. His smile and laugh exuded the joy of one who appreciated every day as a boon.

BLEMISHES

His presidency was not an unalloyed golden age, as his friends concede. He had an autocratic streak. He neglected key policy areas, most critically the fight against HIV/Aids, an omission for which he berated himself in retirement.

He had concluded on Robben Island that when in power he should adopt the consensual politics of his forebears’ royal household. This eased the smooth running of the ANC, an amalgam of races, classes, religions and politics, but he was too loyal to underperforming ministers.

There were other blemishes. As the years passed it emerged he had had to make his share of compromises.

His close relationships with business people were from time to time called into question. He also displayed an almost naive tolerance for the fawning of celebrities. To the distress of some advisers, the first big celebration of his 90th birthday occurred on a London stage alongside the scandal-wracked Amy Winehouse.

BREAKING THE AFRICAN CURSE

Yet as South Africa falters at confronting some of the messy issues of the post-apartheid era, his record rightly appears, if anything, more magical even than when he was President.

His ANC generation has a mythical status: Mandela, Oliver Tambo, Walter Sisulu and so many more. Amid the intermittent stumbles of his successors, the benefits of South Africa’s having embarked on democracy under a man who led with such clarity and principle were all the clearer.

The failure of leadership is arguably the greatest curse to have afflicted sub-Saharan Africa since it won independence. The history of the continent in the second half of the 20th century is littered with the examples of “big men” independence leaders who came to power vowing to liberate their people from the tyranny of the colonial past and then never left office, invariably deploying the rhetoric of liberation to justify misdeeds. The lesson was clear: Once undermined, the independence of democratic institutions is hard to recover.

So Mandela’s unflinching support for the independence of the courts, the media and state institutions set a vital precedent. He respected their rulings even when white judges from the old era ruled in favour of apartheid leaders.

He himself appeared in court when subpoenaed in a dispute over the national rugby squad — and more agonisingly when petitioning for divorce from his second wife, Winnie. For such a private man it was patently painful to have to testify about the intimacies of their relationship. Yet there he stood, stiffly upright in the simple courtroom, testifying in a quavering voice, as the law required.

Strikingly, he did not indulge in the ruinous relativism that had led to so many abuses in Africa passing unrebuked in the continent. But most important of all, he believed in leading by example.

He was the last of Africa’s liberation leaders to take charge and was acutely aware of the need to buck their trend by serving only one term. It was a parting gift of incalculable value to a fledgling democracy. He was indeed the father of the nation.

Do not put me on a pedestal, I am human, he liked to say. He once bemoaned his image as a demigod. Yet, who could dispute that he presides over the pantheon of great leaders of the 20th century? THE FINANCIAL TIMES LIMITED

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Alec Russell, the Financial Times’ news editor, was a correspondent in South Africa from 1993 to 1998, and 2006 to 2008.