When Malaysian English language teachers don’t know English

KUALA LUMPUR — Reports of Malaysian students with poor English and graduates unable to land jobs due to poor speaking skills in the language are by now familiar.

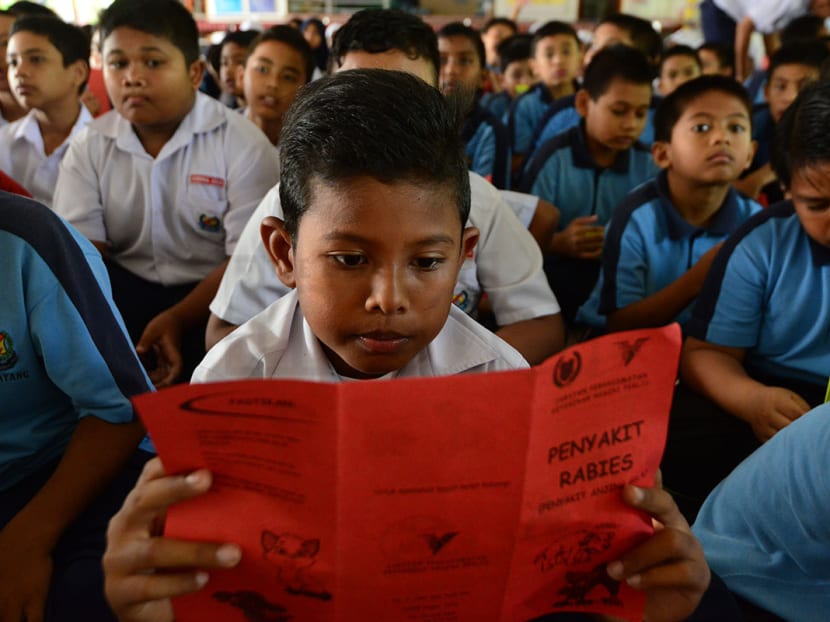

If Malaysia aims to become a high-income nation by 2020, the government must start making English a compulsory pass from primary school, manufacturers say. Photo: The Malaysian Insider

KUALA LUMPUR — Reports of Malaysian students with poor English and graduates unable to land jobs due to poor speaking skills in the language are by now familiar.

But what about the teachers, whose grammar and pronunciation mistakes are still remembered years after by their former students?

Fatimah (not her real name), still vividly recalls the numerous errors her English language teachers made when she was still in school.

Each time she and her classmates stood up to greet their teacher, he would reply, “Good morning. Everyone sits (sic) down”.

Another teacher kept pronouncing “poem” wrong, while another corrected her sentence “the window shattered into a hundred pieces”, to “the window shattered into hundred pieces”.

“The teacher crossed out ‘a’ from my sentence and deducted my marks! “What’s the point of having them teach us English when they don’t have good English themselves?” said Fatimah.

Illustrating the same point is a Facebook post that went viral earlier this year, by user Nadia Fauzi who revealed that her child’s test paper included the question, “What time is the concert starts?”

“This is how bad our English standard is in schools. And when my son corrected her, the teacher called him stupid and said that she’s right and he’s wrong. Wow!” she wrote in a post that quickly went viral.

But it is a scenario that is prevalent across Malaysia – teachers with bad English are instructing Malaysian pupils how to write, read and speak in English. ‘English teachers only speaking English in classes’

One professional communications trainer told The Malaysian Insider that she was surprised by the poor standard of English among some of the 60 English language primary-school teachers she had taught through a Distance and Online Learning Course.

Their ages ranged from mid-20s to late-40s, and some of those taking her classes once a month were from as far as Sabah and Sarawak, she said.

“I was happy with their gung-ho attitude. They were mature. Many were disciplined in completing their online weekly assignments and discussions,” said the trainer, who declined to be named to protect the identity of her students.

“But perhaps I was a bit surprised that some had no knowledge of basic phonetics and phonology, like how to read proper transcriptions in the English dictionary, where to stress and unstress multisyllabic words like ‘computer’ – you need to stress on ‘pu’ not ‘com’ – or the stress-unstressed rhythm of the English language.”

She said the teachers’ English was not up to standards because, like many Malaysian students with a poor grasp of the language, they only spoke English in the classroom.

“English was not practised as there was no one to talk to in the language back in their hometown. Some were not reading and writing as much as they should to improve.

“They enjoyed the occasional English language movies, but ones that are comedic or action-based, with little dialogue,” said the trainer.

Pressured to become teachers

The trainer also taught students taking a diploma in Teaching English as A Second Language (TESL) at a public university located on the east coast.

She said only 10 per cent of her students had good English, and that was because they came from privileged backgrounds, where English was used in their home or hometown.

“But the ones who did not have good English really showed that they wanted to be better and they compensated for it by studying hard, being creative and doing their best in my class.

“I can see that if they carry an intrinsic motivation to improve their English every day, I believe that they would become good teachers and this is already quite an achievement.”

This, then, begged the question: Why did these young Malaysians want to teach English, when they were not proficient in the language themselves?

“Being young, they had no real time to reflect on what they wanted to do, as they applied for a Diploma after completing their SPM.

“They were not able to think about the future but were going through the motions of studying, then passing exams, then graduating,” she said.

She said some confided in her that their parents – usually government employees or from the low-income group – told them to become English language teachers as it was a steady-paying job.

“So they took the course because they did not want to upset their parents.

“Those who were obedient children followed their parents’ advice and did very well in class, but the ones who resented it would skip classes and were demotivated,” she said.

‘I feel demotivated by my English proficiency’

On Facebook, a young English language teacher shared how she was demotivated over her lack of proficiency in the language, but was later mollified when her colleagues sought her help to compose a message in English.

When approached by The Malaysian Insider, the private school teacher, who declined to be identified for fear of backlash, confided that she lacked confidence because she was not well-versed in writing in English.

“I noticed that I’m good in speaking, while not so ‘good’ in writing. Maybe because it’s also not my first language,” she wrote in a message to The Malaysian Insider.

“When you don’t get support from people around you, and people just keep commenting, that will put yourselves down,” she continued in her typed message.

But she said she was confident when teaching English to her 11 and 12-year-old students because they loved and respected her.

“They look up on me although they’re better than me. That’s the respect I can see. Sometimes we are better than our teachers,” she wrote, adding a winking emoticon.

Her love for children and teaching motivated her to become an English teacher in the first place, she added.

“I love sharing and I love for being attached with humans,” she wrote.

She said the school had recently begun providing training to its English language teachers, but she also made a personal effort “by studying extra lessons, add more general knowledge and read more books”.

Efficacy of foreign English trainers

The government is aware of the language problems among local English teachers – according to DAP lawmaker Zairil Khir Johari, Putrajaya has spent RM500 million (S$166 million) since 2011 to hire foreign English language mentors under the Program Menutur Jati Bahasa Inggeris (PPJBI) programme.

“These mentors are supposed to train our local teachers, but results differ from place to place. There is little consistency.

“While the idea of getting foreign English trainers is good, there are many question marks about its efficacy and whether our teachers get enough exposure and training,” he told The Malaysian Insider.

Mr Zairil said the most basic solution to solving this issue was to simply hire good English teachers.

“Without good English teachers we can try whatever policy, but it won’t work. So we need to concentrate on upskilling teachers,” said the Bukit Bendera MP.

He added that the government needed to encourage the use of English, as immersion was the best way to learn the language.

This was why he was in favour of the dual language progamme (DLP), and a pilot programme allowing schools to choose their language of instruction.

“Right now, it’s too early to comment, but allowing autonomy and choice is the right way forward,” said Mr Zairil.

But he hit out on Putrajaya for reducing the Budget 2016 allocation for the teaching and learning of English to RM135 million.

He said it was a far cry from the RM208 million annually allocated for the Uphold Bahasa Malaysia and Strengthen the English Language (MBMMBI) policy.

“Since its introduction, MBMMBI gets about RM200 million a year, but for 2016 it was halved to RM97 million a year.

“And even with the two new programmes (DLP and High Immersive Programme), it only goes up to RM135 million. So the government’s rhetoric doesn’t match the allocation,” he said.

The Malaysian Insider is trying to get a response from Deputy Education Minister P Kamalanathan. THE MALAYSIAN INSIDER